Centro histórico de la Ciudad de México

Historical Monuments Zone

Abstract

Capital of the Mexica people and viceregal capital, also known as the “City of Palaces.” Its architectural and cultural development has been linked to the different governments it has had throughout its history. Today, pre-Hispanic remains, Baroque churches, Neoclassical and Art Deco buildings, as well as modern skyscrapers converge in the heart of the country’s dizzying capital.

The Mexica, who came from the mythical place known as Aztlán, arrived on an islet in the middle of Lake Texcoco in the year 1325. There they founded the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, a ceremonial center in which they erected twin temples dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc. Upon the arrival of the Spanish, Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan had formed the Triple Alliance, a political entity that dominated Mesoamerica, exercising military and economic control over an extensive territory that extended over the present-day territories of Mexico City, State of Mexico, Morelos, Oaxaca, Puebla, Veracruz and Tabasco. The Mexica waged war on these peoples and, having defeating them, imposed tributary obligations on them, and sometimes established military garrisons in their territories.

In 1521 the troops of Hernán Cortés, made up of Spanish and indigenous soldiers, defeated the Mexica and took Tenochtitlan. After the victory, Cortés established himself temporarily in Coyoacán while debris and corpses were removed from the city.

Mexico City was built on the ruins of the old Mexica foundations following the European ideals of urban planning of the time: a plaza surrounded by straight streets arranged in the form of a checkerboard. However, the construction materials of the Mexican buildings were reused and the structure of the pre-Hispanic city was taken as a basis, especially its roads and its division into 4 quadrants, which gave rise to the four indigenous neighborhoods. The city was divided into the Republic of Spaniards, which was built within the islet, and the Republic of Indians, made up of four neighborhoods located on the outskirts of the city, which had an irregular layout. These neighborhoods were: San Juan Moyotlan, San Pablo Teopan, San Sebastián Atzacualco and Santa María Cuepopan.

The layout of the city center has undergone several transformations over time. The first plan was that of Hernán Cortés, who established the seat of political power in the Axayácatl Palace, where the Monte de Piedad is currently located. In 1525 the construction of the first Cathedral began, with an altar oriented towards the east, with the result that the space around which the buildings representing the political and religious power were gathered was located to the west of the current cathedral.

However, Cortés’s project was never completed. With the arrival of the first viceroy, in 1535, the public spaces and seats of power changed location, as they were concentrated around the old “market square,” now known as the Zócalo. Likewise, the new building of the cathedral was in the north, so that its door faced towards the south, towards the main square.

In the 16th century, monasteries, schools and hospitals began to be built in order to meet the religious, moral, educational and health needs of the population of New Spain. The first monasteries to be founded were those of San Francisco, Santo Domingo and San Agustín. The evangelization of the indigenous people of the city was carried out there, and schools such as that of San José de los Naturales were created, where the children of the indigenous chiefs were taught. Later, the Jesuits arrived in New Spain, and devoted themselves largely to the education of both criollos and Spaniards, as well as mestizos and indigenous people, founding various schools in the city.

Likewise, a number of convents were founded, places of seclusion for widows, prostitutes and orphans, as well as schools for the education of girls. The city also had numerous parish churches, such as El Sagrario, Santa Vera Cruz, San Miguel and Santa Catharina Mártir.

Mexico City was the political and economic center of the viceroyalty, seat of the viceregal court and of the archbishopric of Mexico. Activities such as commerce flourished here, focused on the Parián, a market located in the Zócalo where products from China and the Philippines could be found, brought from the East by the Nao de China ships.

In the 18th century the city began to undergo changes due to the ideas of the Enlightenment. The streets were paved, public lighting was installed by means of lanterns, street names and house numbers were written on tiles, and the layout of the streets and the neighborhoods was ordered. Likewise, at the end of the 18th century the exuberance of Baroque architecture began to be displaced by the sobriety of the Neoclassical style. At this time the buildings known today as the Palacio de Minería and the Academia de San Carlos were built and Neoclassical elements were inserted in the facade of the Casa de Moneda. The sculptor Manuel Tolsá made the equestrian statue of King Carlos IV, known as the “little horse,” which was placed in the middle of the Zócalo.

With the declaration of independence of Mexico in 1821, Mexico City ceased to be the center of the Spanish Empire in New Spain and became the capital city of a new American nation. The fighting of the independence war disrupted the life of the city, which was plunged into chaos. The city underwent several transformations such as the renaming of the squares and streets, and the removal of the “little horse” statue from the main square, which became known as the Plaza de la Constitución. Busts of the Spanish monarchs and the noble coats of arms were removed from the facades of the houses.

In the second half of the 19th century, the city underwent major transformations caused by the enactment of the Reform Laws (1855-1867) that abolished ecclesiastical property. With this, the liberal governments sought the secularization of urban space in order to assert the republican identity of the city. In 1861 dozens of convents and religious buildings were demolished or divided, which led to the opening up of new streets. For example, the Monastery of San Francisco, located on the present-day Madero Street was divided, giving rise to the streets of Gante and 16 de Septiembre. The remains of the monastery were used as a hotel, circus, stables and Protestant church.

During the Porfiriato period the city was again transformed in line with the ideals of modernity and the models of French architecture. Examples of this are the Postal Palace, the Iron Palace and the Palace of Fine Arts, whose construction was interrupted by the Mexican Revolution and only completed in 1934. Mexico City was the scene of several historical events during the Revolution: the triumphal entry to the city of Madero on June 6, 1911 down the street that now bears his name, and the entry of Emiliano Zapata and Francisco Villa in 1914.

In the post-revolutionary era, the interiors of the downtown buildings were transformed to become canvases for Mexican Muralism; new streets were opened such as avenues 20 de Noviembre and San Juan de Letrán, and new buildings were erected such as the Bank of Mexico, the Department of the Federal District and the Latin American Tower, which broke with the horizontal character of the city center for the first time. Also during this period many buildings disappeared or were transformed into cinemas, warehouses or shops.

In the 1960s, the construction of the metro system transformed how the inhabitants of the city moved around, and also led to important archaeological finds. In 1978, a large stone relief of the goddess Coyolxauhqui was found, which led to the excavation of the Templo Mayor, the most important ceremonial site of the Mexica.

Today, the historic center of Mexico City is distinguished by its intense cultural activity in its many museums, theaters and concert halls, as well as by its bustling commercial activity and services such as hotels, restaurants and bars.

The current perimeter of the Historic Center expands beyond the island on which the pre-Hispanic city of Tenochtitlan was founded. Its heart remains the Plaza de la Constitución, known as the Zócalo, the second largest in the world with an area of 46 800 m2.

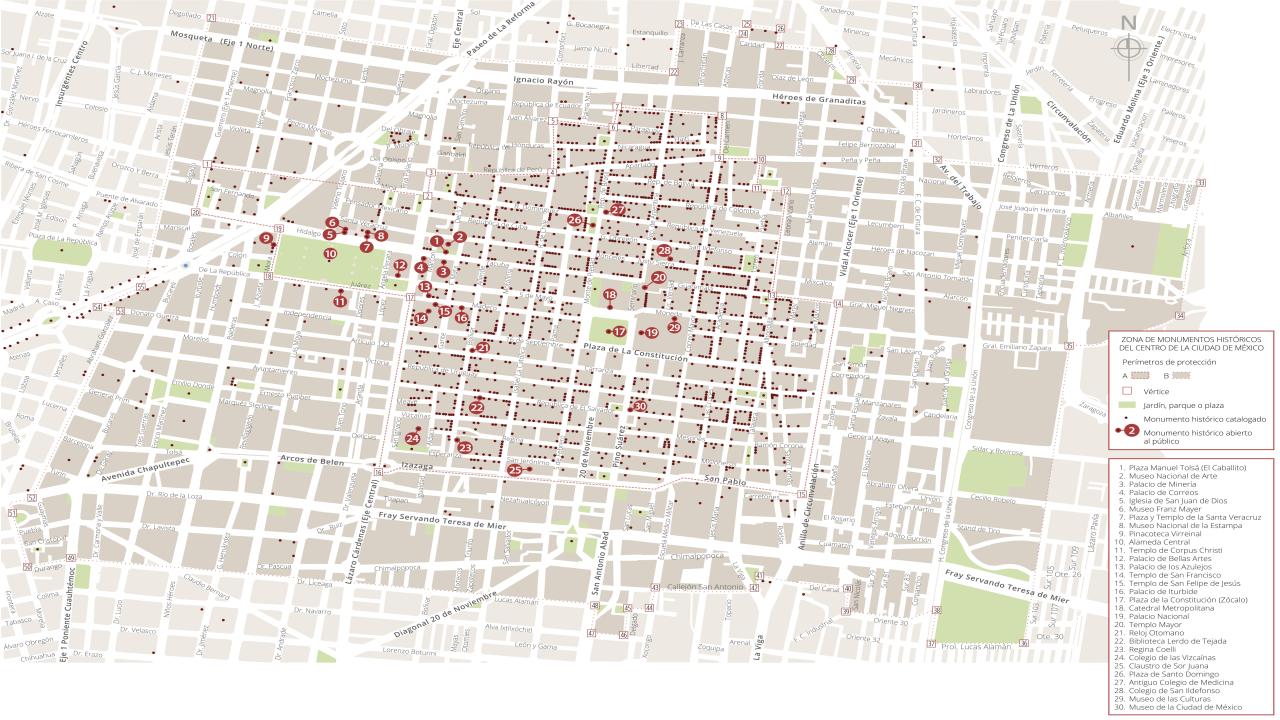

The Historic Center of Mexico City was declared a Zone of Historical Monuments in 1980, and it was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987. The area of historical monuments covers 9.1 km2 and is made up of 668 blocks that bring together numerous buildings of historical and artistic interest. It comprises pre-Hispanic remains and constructions dating from the 16th to the 20th centuries. Some of its most emblematic buildings are: the Metropolitan Cathedral, the National Palace, the Palace of Fine Arts, the Churches and Formeres Monasteries of San Agustín, of Santo Domingo, of la Enseñanza, of San Francisco, the Former College of San Ildefonso, the National Monte de Piedad, the Mining Palace, the National Museum of Art, the Postal Palace, the Iturbide Palace, the National Museum of Cultures, the Former Palace of the Inquisition, the Former Church of San Pedro and San Pablo, among others.

Catedral Metropolitana

The original Mexico City Cathedral was built by Hernán Cortés in the Plaza Mayor of Mexico, using monoliths from the old teocali for the foundations and the bases of the pillars. Martín de Sepúlveda directed the construction of the temple, which was inaugurated in 1532.

Catedral Metropolitana

The original Mexico City Cathedral was built by Hernán Cortés in the Plaza Mayor of Mexico, using monoliths from the old teocali for the foundations and the bases of the pillars. Martín de Sepúlveda directed the construction of the temple, which was inaugurated in 1532.

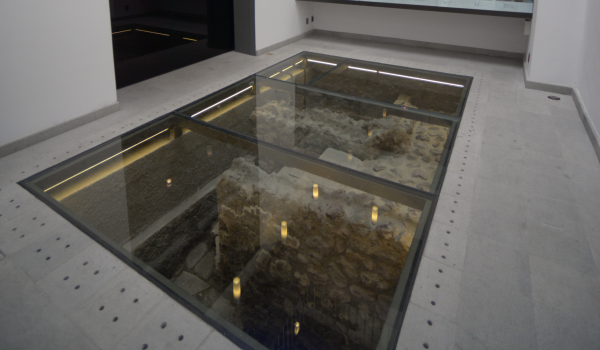

Atrio de la Catedral de México, Ventana 1

Archaeological window

Atrio de la Catedral de México, Ventana 2

Archaeological window

Atrio de la Catedral de México, Ventana 3

Archaeological window

Atrio de la Catedral de México, Ventana 4

Archaeological window

Palacio de Minería

In 1793, the site was purchased with the help of the Second Count of Revillagigedo, Juan Vicente Güemes Pacheco y Padilla. The architect Manuel Tolsá designed and directed this work between 1797 and 1813.

Palacio de Minería

In 1793, the site was purchased with the help of the Second Count of Revillagigedo, Juan Vicente Güemes Pacheco y Padilla. The architect Manuel Tolsá designed and directed this work between 1797 and 1813. Due to the subsidence of the ground, Antonio Villard rebuilt the building in 1830 without altering its form. It served as the headquarters for the Ministry of Public Instruction and Worship, the Academy of Sciences and Literature, the Ministry of Justice, and the Contributions Office. From 1867 to 1954, it housed the Special School of Engineers.

Templo de la Profesa

In this building resided the first Jesuits of the Fourth Vow.

Museo Nacional de San Carlos

The Old Buenavista Palace, attributed to architect Manuel Tolsá, began construction in the late 18th century at the request of the Marquise of Selva Nevada, Antonia Gómez Rodríguez de Pedrozo y Soria, as a gift for her son, the Count of Buenavista.

Museo Nacional de San Carlos

The Old Buenavista Palace, attributed to architect Manuel Tolsá, began construction in the late 18th century at the request of the Marquise of Selva Nevada, Antonia Gómez Rodríguez de Pedrozo y Soria, as a gift for her son, the Count of Buenavista. Its predominant style is neoclassical, but it features some Baroque elements.

Casa de las Campanas "Primera Imprenta de América"

An 18th-century building that housed the workshop where the bells for the first churches in Mexico City were cast. This building also became the site of the first printing house on the continent.

Casa de las Campanas "Primera Imprenta de América"

An 18th-century building that housed the workshop where the bells for the first churches in Mexico City were cast. This building also became the site of the first printing house on the continent.

Plaza de Santo Domingo

A space created in the mid-16th century by Dominican friars to provide a view and splendor to their church. Its urban layout has remained unchanged, but the surrounding buildings have varied over time.

Plaza de Santo Domingo

A space created in the mid-16th century by Dominican friars to provide a view and splendor to their church. Its urban layout has remained unchanged, but the surrounding buildings have varied over time.

Antigua Plazuela del Marqués o Plaza del Empedradillo

A space laid out since the 16th century, located between the Monte de Piedad and the Metropolitan Cathedral. It was known as the Plaza del Marqués because to the west was the property of Cortés and his heirs, who held the Marquessate of the Valley of Oaxaca.

Antigua Plazuela del Marqués o Plaza del Empedradillo

A space laid out since the 16th century, located between the Monte de Piedad and the Metropolitan Cathedral. It was known as the Plaza del Marqués because to the west was the property of Cortés and his heirs, who held the Marquessate of the Valley of Oaxaca.

Plaza de San Miguel

18th-century space

Museo de Medicina (Antigua Escuela de Medicina)

This land was purchased from Juan Velázquez de Salazar in 1578; on it, the Inquisition's facilities and the residences of the inquisitors were built. Throughout the 17th century, architects Bartolomé Bernal and Pedro Durán carried out various renovations and expansions.

Museo de Medicina (Antigua Escuela de Medicina)

This land was purchased from Juan Velázquez de Salazar in 1578; on it, the Inquisition's facilities and the residences of the inquisitors were built. Throughout the 17th century, architects Bartolomé Bernal and Pedro Durán carried out various renovations and expansions. On December 1, 1732, the reconstruction work began, which lasted for five years. In 1853, the professors of the School of Medicine demanded the building as payment for their overdue salaries. In 1879, a second floor was added.

Antigua Casa del Primer Protomedicato

This 18th-century complex was the perpetual prison of the Inquisition. It was originally intended for the first Protomedicato of New Spain in the 17th century. In 1979, the building was reconstructed, with special areas designed for the Department of History at the Faculty of Medicine.

Antigua Casa del Primer Protomedicato

This 18th-century complex was the perpetual prison of the Inquisition. It was originally intended for the first Protomedicato of New Spain in the 17th century. In 1979, the building was reconstructed, with special areas designed for the Department of History at the Faculty of Medicine.

Academia de San Carlos

A 16th-century building that housed the second hospital in the city, founded by Fray Juan de Zumárraga. It had a chapel open to the public dedicated to the Virgin of Sorrows, with a façade facing the main street.

Academia de San Carlos

A 16th-century building that housed the second hospital in the city, founded by Fray Juan de Zumárraga. It had a chapel open to the public dedicated to the Virgin of Sorrows, with a façade facing the main street. The so-called "Hospital del Amor de Dios" closed its doors in 1788 and moved to the San Andrés Hospital. In 1781, Master Fernando José Mangino, representing the engraver Jerónimo Antonio Gil, presented the viceroy with a project for an academy of painting, sculpture, and architecture. It wasn't until 1791 that this building was adapted for the Royal Academy of the Three Noble Arts of San Carlos of New Spain. In 1845, it became the first institution to have gas lighting. It now houses the Academy Museum.

Antiguo Templo de San Pedro y San Pablo (Museo de las Constituciones)

The building was constructed on the land granted to the Jesuits between 1576 and 1603, under the direction of Jesuit architect Diego López de Arbaiza. After the Jesuits were expelled, the temple was closed to worship, and in 1822, it became the site of the First Mexican Congress.

Antiguo Templo de San Pedro y San Pablo (Museo de las Constituciones)

The building was constructed on the land granted to the Jesuits between 1576 and 1603, under the direction of Jesuit architect Diego López de Arbaiza. After the Jesuits were expelled, the temple was closed to worship, and in 1822, it became the site of the First Mexican Congress. Two years later, it housed the Legislative Assembly, where the first president of Mexico, Guadalupe Victoria, took his oath. Later, it hosted the Library of the Colegio de San Gregorio and, after the Revolution, became the National Hemeroteca. Around 1990, it was restored to become the Museum of Light, as part of the UNAM heritage. It currently houses the Museum of the Constitutions.

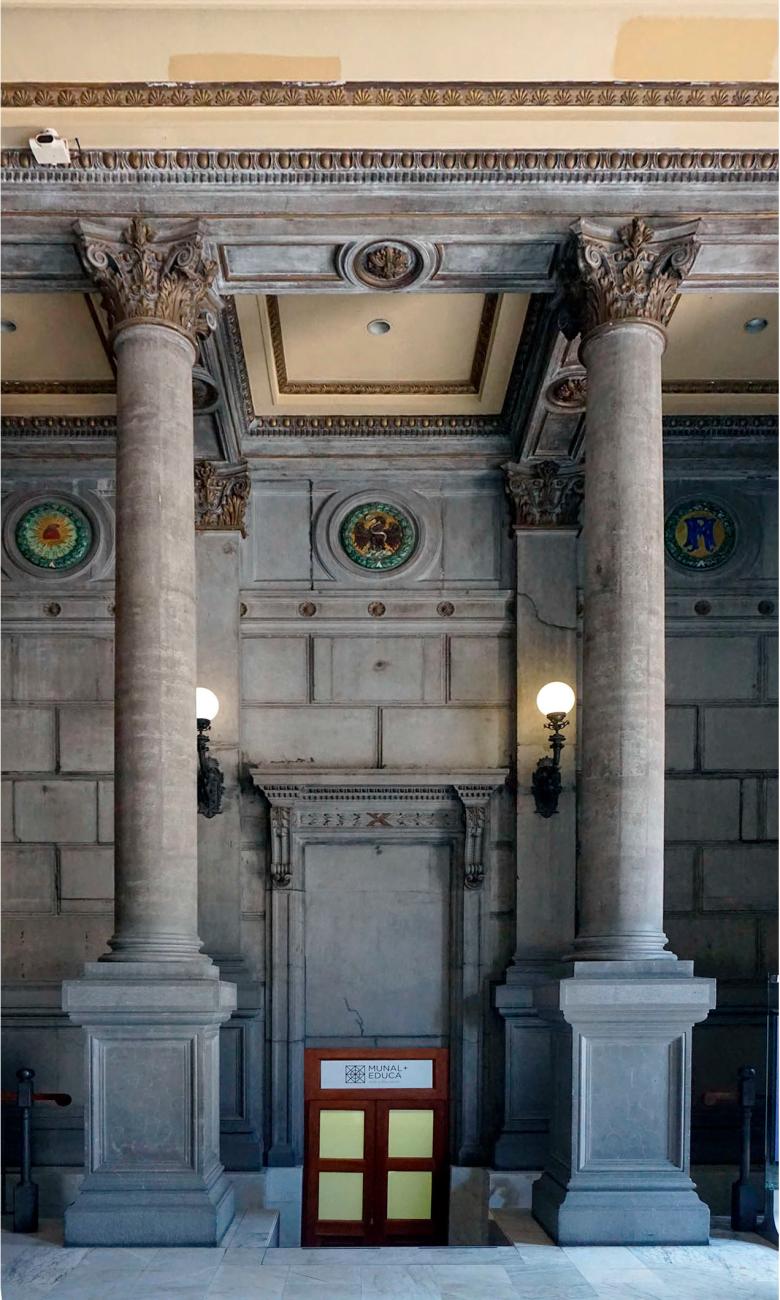

Museo Nacional de Arte

The first use of this building was during the 16th century when María de Aguilar and Melchor de Cuéllar supported the foundation of a College-Seminary for the Society of Jesus. The construction of this college was completed by Andrés de Carvajal y Tapia in 1695.

n>

Museo Nacional de Arte

The first use of this building was during the 16th century when María de Aguilar and Melchor de Cuéllar supported the foundation of a College-Seminary for the Society of Jesus. The construction of this college was completed by Andrés de Carvajal y Tapia in 1695.

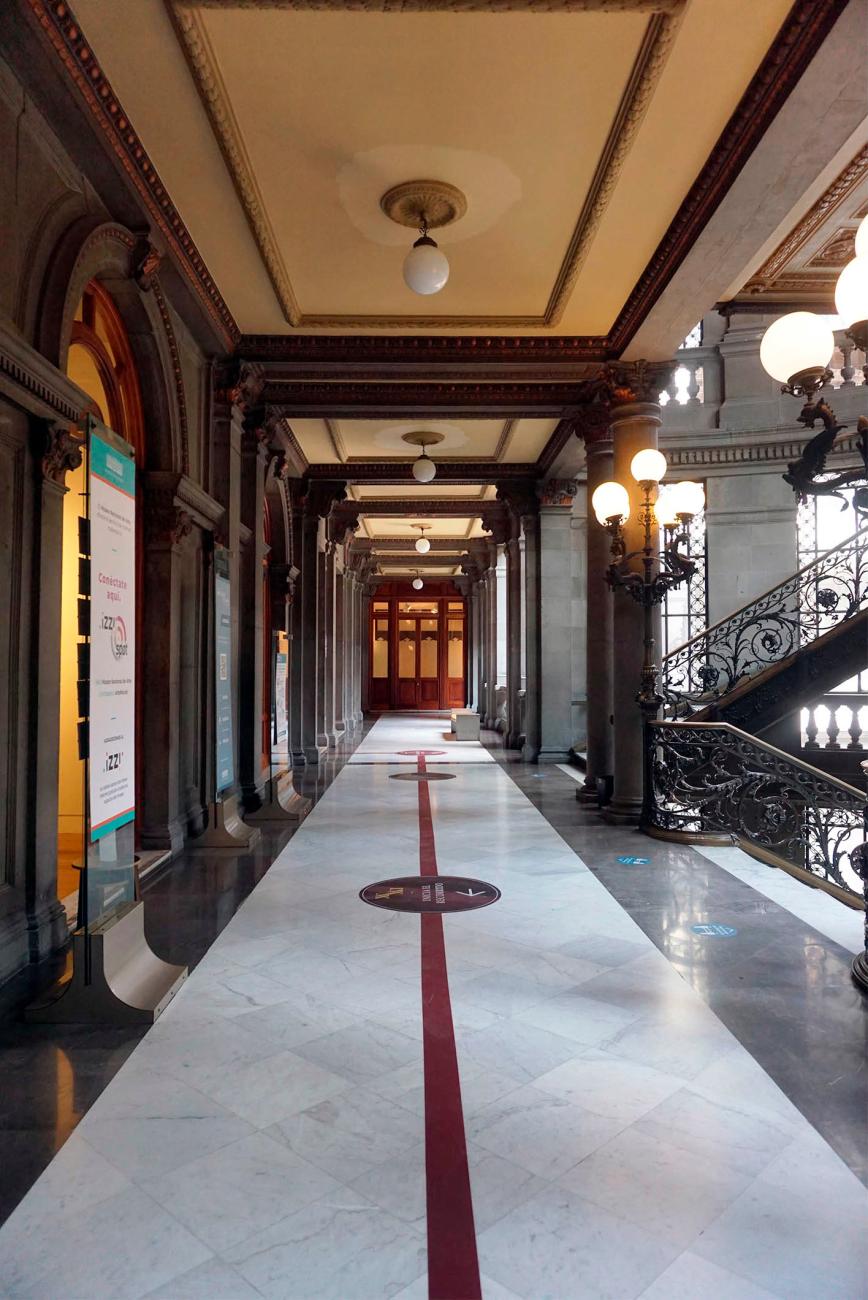

Palacio Postal

During the 18th century, this site served as the Royal Thirds Hospital, which was demolished to construct the Post Office building under the direction of military engineer Gonzalo Garita, with a design by the Italian architect Adamo Boari Dandini; the first stone was laid in 1902.

n>

Palacio Postal

During the 18th century, this site served as the Royal Thirds Hospital, which was demolished to construct the Post Office building under the direction of military engineer Gonzalo Garita, with a design by the Italian architect Adamo Boari Dandini; the first stone was laid in 1902.

Banco de México

It was built between 1903 and 1905 using the "Chicago" technique, which consisted of an iron grid encased in concrete.

n>

Banco de México

It was built between 1903 and 1905 using the "Chicago" technique, which consisted of an iron grid encased in concrete.

Palacio de Bellas Artes

In the context of the centennial celebration of Independence, there was a need for a theater space. The project was led by Italian architect Adamo Boari, incorporating a blend of Art Nouveau elements and Mexican architecture.

n>

Palacio de Bellas Artes

In the context of the centennial celebration of Independence, there was a need for a theater space. The project was led by Italian architect Adamo Boari, incorporating a blend of Art Nouveau elements and Mexican architecture. In November 1904, President Porfirio Díaz laid the cornerstone of the building, which was inaugurated on September 29, 1934.