Santiago de Querétaro

Historical Monuments Zone

Abstract

A viceregal city characterized by the Baroque architecture of its temples, monasteries and large houses, as well as by its fountains and its imposing aqueduct. The layout of its streets reflects its origins as an indigenous town and its transformation into one of the richest and most important cities of the viceroyalty of New Spain.

The capital city of the state of Querétaro is located in the south of the Bajío region. Founded in the 16th century, it was the gateway to the north for the colonization of the mining areas of Zacatecas, Guanajuato and San Luís Potosí, located as it was on the Camino Real Tierra Adentro (Royal Inland Road).

Its name, Santiago de Querétaro, is of mixed origin: the word “Querétaro” comes from the Purépecha “K’erhiretarhu” or “K’erendarhu,” which means “place of large stones or rocks”; while the dedication to Santiago refers to the legend of its foundation, according to which the saint interceded in favor of the Spanish during a battle against the Chichimecas, causing them to surrender to the cross of Christ.

Upon the arrival of the Spanish, the current territory of the city of Querétaro was occupied by a group of Otomi who had been displaced from a site called Jilotepec. The Spaniards and the indigenous people negotiated the establishment of a tributary system and the baptism of several Otomi and Chichimecas, including their leader and founder Conni or Conín, who received the Christian name of Fernando de Tapia.

The city of Querétaro was founded in 1531. At first it was the northernmost settlement in New Spain, which is why it was considered a key point for territorial expansion and for the propagation of the Christian faith through the evangelization work carried out by the religious orders among the indigenous people. It is for this reason that the first building that was built in Querétaro was the monastery of San Francisco.

The urban plan of Querétaro is of mixed origin, and a product of the irregular geography of the valley in which it is located. Its distribution can be divided into two parts: the first, the indigenous street plan that was laid out between 1531 and 1551 by the Otomi chiefs, based on the situation and topography of the Sangremal hill; the second, the Spanish plan surveyed between 1551 and 1600. Juan Sánchez de Alanís is credited with having organized the blocks in the form of a checkerboard. The result of these processes is a mixture of both projects, where rectilinear and winding streets merge in an irregular grid. Today the indigenous layout can still be seen to the east of Juárez Street, and the Spanish to the west.

The city grew in importance from the 16th century onwards due to its location on the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, the main link between the mining centers in the north and Mexico City, capital of New Spain. During the 17th century there were two major events: the renovation and expansion of the San Francisco monastery in 1640, and the recognition of Querétaro as the “third city of the kingdom” in 1671.

By the beginning of the 18th century, the different neighborhoods of Querétaro were already linked up, creating a single urban area. It was a time of economic prosperity for the city, meaning there were several wealthy people who sponsored significant architectural works such as churches, monasteries and civil buildings. These prominent figures included the Marquis Juan Antonio de Urrutia y Arana, who backed the construction of the aqueduct, known as Los Arcos.

This project reflected the growing city’s need for a reliable water source. The aqueduct was built between 1726 and 1735, and is 1,298 meters long. It transported clean water from the springs of the Cañada to the Santa Cruz monastery, located on the Sangremal hill, and from there descended to the city, where private pipes supplied the most important houses, while public fountains or wells were scattered across the neighborhoods and monasteries to bring water to the rest of the inhabitants. Some of these wells were ornamented with Baroque elements or religious images.

The city’s architecture is dominated by the Baroque style, characterized by the abundant use of ornamentation. The beauty of its churches, monasteries, civil buildings and mansion houses reflects the social status and economic power of its inhabitants in the viceregal era. One of the most popular construction materials was pink and gray cantera stone, which is abundant in the region. One of the distinctive features of Queretaro architecture are the arches of its mansions and cloisters, which are influenced by the Mudéjar style and are composed of a combination of straight lines and curves that create the illusion of movement. Other representative features are the use of Greco-Latin elements in columns and sculptures on the facades, as well as the ornamentation of the architecture with mural paintings on walls, ceilings, arches and vaults.

Querétaro is also famous for its role in starting the struggle for Mexican independence. In 1810 it was the site of the “Conspiracy of Querétaro” where the movement that would lead to independence was forged.

Other historical events that marked the city were the execution of Emperor Maximiliano in the Cerro de las Campanas in 1867; the construction of the railway that connects Querétaro with San Juan del Río and Mexico City, begun in 1878; and the celebration of the Constituent Congress convened by Venustiano Carranza in 1917 and held at the Iturbide Theater, where the Constitution that still governs Mexico today was promulgated.

Among the city’s most deeply rooted traditions are the annual celebration of Holy Week, the festival of the founding of the city held every July 25, and the festival of the Holy Cross that takes place in September and is characterized by conchero dances.

The Zone of Historical Monuments was decreed in 1981 with an area of 4 km2 and is made up of 203 blocks comprising buildings of historical value built between the 16th and 19th centuries, among them religious buildings such as the monasteries of San Francisco de Asís, Santo Domingo de Guzmán and its Rosario Chapel, San Antonio, San Agustín, the Oratory of San Felipe Neri, the convent of Santa Clara and Nuestra Señora del Carmen; the parish churches of Santiago, San Sebastián and Santa Ana; and the churches and chapels of the Congregation of Guadalupe, La Merced and of the Holy Spirit, and the Church of Santa Rosa de Viterbo.

Other historical buildings have been destined for educational, welfare and civil purposes; these include the Hospitals of the Immaculate Conception and of the Charity of Divine Providence, the Josefa Vergara Children’s Hospice, the Rivera Old People’s Home; the Colleges of Propaganda Fide de la Santa Cruz de los Milagros and its Chapel of the Assumption, the Real de San Ignacio de Loyola and San Francisco Javier, the Real de Santa Rosa de Viterbo and the Real de San José de las Carmelitas Descalzas.

Among the private mansion houses, the Casa de Escala, Casa del Conde de la Sierra Gorda, Casa del Marqués and Casa de la Marquesa are of particular note.

Querétaro was declared a Zone of Historical Monuments on March 30, 1981 and a World Heritage Site by UNESCO on December 7, 1996. On August 1, 2010 it was also listed as part of the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro route.

Acueducto

The aqueduct was built between 1726 and 1735 and is 1,298 meters long. It transported clean water from the springs of La Cañada to the convent of Santa Cruz, located on Sangremal Hill, from where it descended to the city, which had private piped channels in the most important mansions, as well as public fountains or “water boxes” distributed throughout the neighborhoods and convents to bring water to all the inhabitants. Some of these water boxes were decorated with Baroque elements or religious images.

Casa Ecala

This 18th-century New Spanish Baroque house belonged to councilman Tomás López de Ecala. The building has four portals on the façade, with three-centered arches resting on pillars that allow pedestrian traffic.

Casa Ecala

This 18th-century New Spanish Baroque house belonged to councilman Tomás López de Ecala. The building has four portals on the façade, with three-centered arches resting on pillars that allow pedestrian traffic. On the ground floor, there is a fountain and the López de Ecala family crest, which were added in the last third of the 20th century. On the second floor, there is a covered gallery that leads to the main room, which has balconies overlooking the main square. Only part of the house has a third floor, where there is a viewpoint. When the city of Querétaro was declared the capital of the Republic in 1916, the Ministry of Communications was established in this building. In 1923, it became the property of the Mexican Electric Company, and in 1943, it passed to the Mexican Electric Industry of the Center. Later, it was used as the Municipal House of Culture, Municipal Library, and headquarters of the Mexican Society of Geography and Statistics. In 1979, it housed the Ministry of Tourism, and currently, it houses the state offices of Integral Family Development.

Casa de la Marquesa

This building was completed in 1756 and was the home of Don Antonio Alday.

Casa de la Marquesa

This building was completed in 1756 and was the home of Don Antonio Alday. It later became the residence of Paula Guerrero Dávila, Marquise of Villa del Villar del Águila, who received Agustín de Iturbide in September 1821 on his way to Mexico City to make his triumphant entry with the Trigarante Army.

Templo de San Felipe Neri

In 1755, Father Martín de San Cayetano y Jorganes began founding the Oratory and Congregation of San Felipe Neri. The first mass in this temple was held on November 21, 1763. The organ in its choir is noteworthy, considered one of the best in the city.

Templo de San Felipe Neri

In 1755, Father Martín de San Cayetano y Jorganes began founding the Oratory and Congregation of San Felipe Neri. The first mass in this temple was held on November 21, 1763. The organ in its choir is noteworthy, considered one of the best in the city. Much of the building is in poor condition as a result of having been used as barracks.

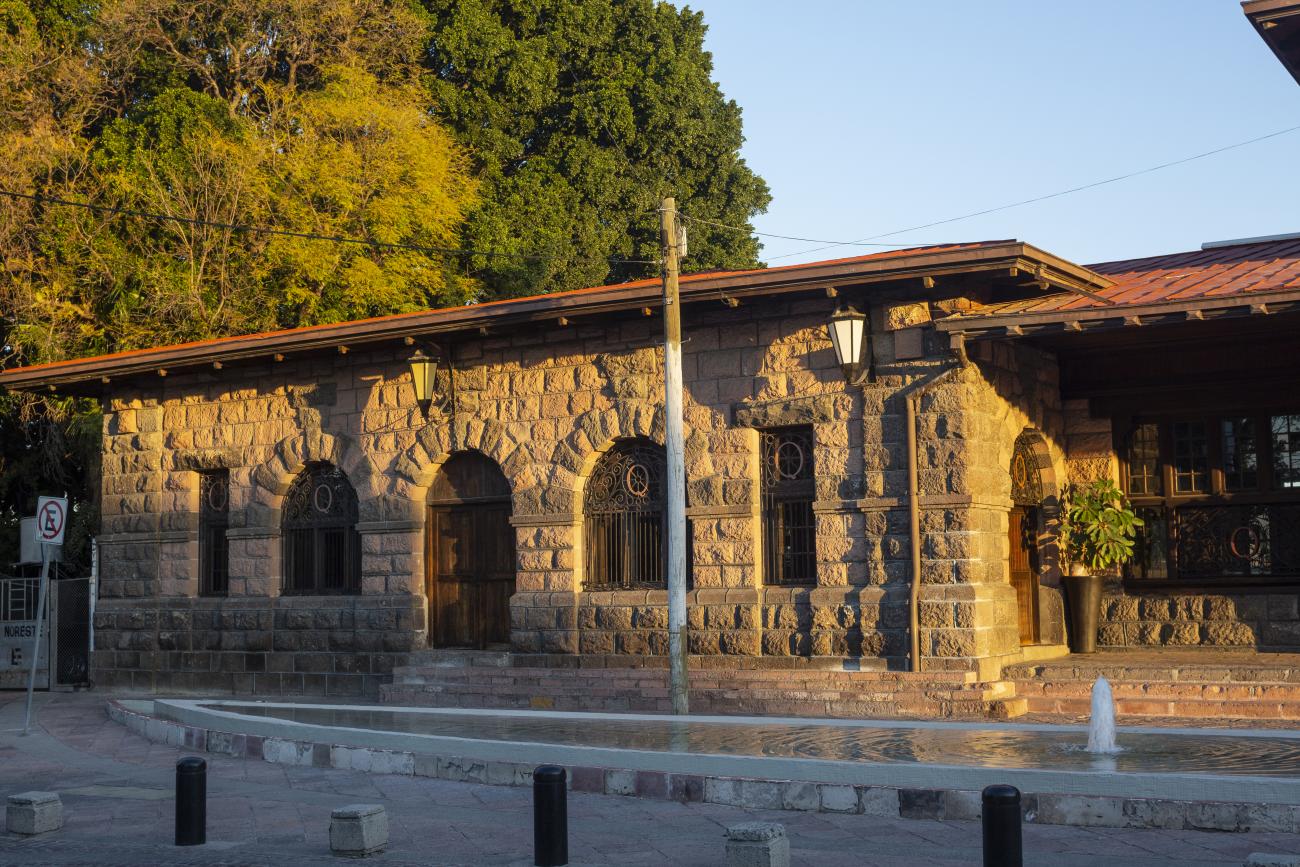

Estación Quéretaro

On March 21, 1878, construction began on the Queretano Railroad, which would connect the city with San Juan del Río; however, the work was never completed, and in 1880 it merged with the Central Railroad. In November 1903, the Mexican National Railroad station was officially inaugurated.

Estación Quéretaro

On March 21, 1878, construction began on the Queretano Railroad, which would connect the city with San Juan del Río; however, the work was never completed, and in 1880 it merged with the Central Railroad. In November 1903, the Mexican National Railroad station was officially inaugurated.

Fuente de Neptuno

The fountain was originally located in a corner of the garden of the San Antonio convent. The structure supporting the basin was designed by Francisco Eduardo Tresguerras, and the statue of Neptune, the Latin god of the sea, was sculpted by Juan Izguerra.

Fuente de Neptuno

The fountain was originally located in a corner of the garden of the San Antonio convent. The structure supporting the basin was designed by Francisco Eduardo Tresguerras, and the statue of Neptune, the Latin god of the sea, was sculpted by Juan Izguerra. In 1848, a market was built in the convent garden; it was then that the fountain lost two pavilions that flanked the central structure, the back was carved to imitate the front, and the niche became an opening. It is currently located in the Garden of Santa Clara, and the sculpture of Neptune was replaced by a replica made by Abraham González on July 23, 1987. The original has been restored and is kept in a gallery of the Municipal Presidency.

Jardín Zenea

This garden was part of the atrium of the Franciscan convent, where the Neptune Fountain was located, which was removed to build a bullring. In 1863, the church collapsed, and in 1867, the space was transformed into a market, a garden, and the Gran Hotel.

Jardín Zenea

This garden was part of the atrium of the Franciscan convent, where the Neptune Fountain was located, which was removed to build a bullring. In 1863, the church collapsed, and in 1867, the space was transformed into a market, a garden, and the Gran Hotel. The garden was laid out during the governorship of Benito Santos Zenea and was embellished with the Hebe fountain donated by Cayetano Rubio in 1874. The space was remodeled in 1990.

Casa de la Corregidora

In the 18th century, the City Council purchased a plot of land owned by María Jimena, an indigenous woman from Querétaro, for the construction of the Royal Houses and Town Hall, which was completed in 1770.

Casa de la Corregidora

In the 18th century, the City Council purchased a plot of land owned by María Jimena, an indigenous woman from Querétaro, for the construction of the Royal Houses and Town Hall, which was completed in 1770. This building witnessed the beginnings of independence, as on September 13, 1810, the corregidora Josefa Ortíz de Domínguez was imprisoned there and sent word of the danger to the priest of Dolores, Don Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. After independence, in 1821, the building was designated as the State Government Palace. In 1856, its archives were looted by the troops of Tomás Mejía. In 1868, the State Government Offices were moved to the building they still occupy today, on the corner of Madero and Ocampo, and the Plaza Mayor building was designated as the Municipal Palace when José María Iglesias established his government in 1876.

Plaza de Armas

The first main square in Querétaro was the lower square, or San Francisco Square, which was later renamed Recreo Square, where the first town hall buildings were located.

Plaza de Armas

The first main square in Querétaro was the lower square, or San Francisco Square, which was later renamed Recreo Square, where the first town hall buildings were located. When new royal houses were built to the north of the upper square, now Independence Square, it became the “main” square, with the main temple excluded from its enclosure and somewhat distant. The square was intended to be rectangular in shape, but it turned out to be an irregular polygon, which is now concealed by the walkways on three of its sides. In the center is a monument to the Basque Juan Antonio de Urrutia y Arana, Marquis of Villar del Águila, who was responsible for the construction of the underground sewer, the aqueduct bridge, and several public fountains. The monument was created by the sculptor Luis Romero. The square also features sculptures of Christopher Columbus and Juan Antonio de Urrutia.

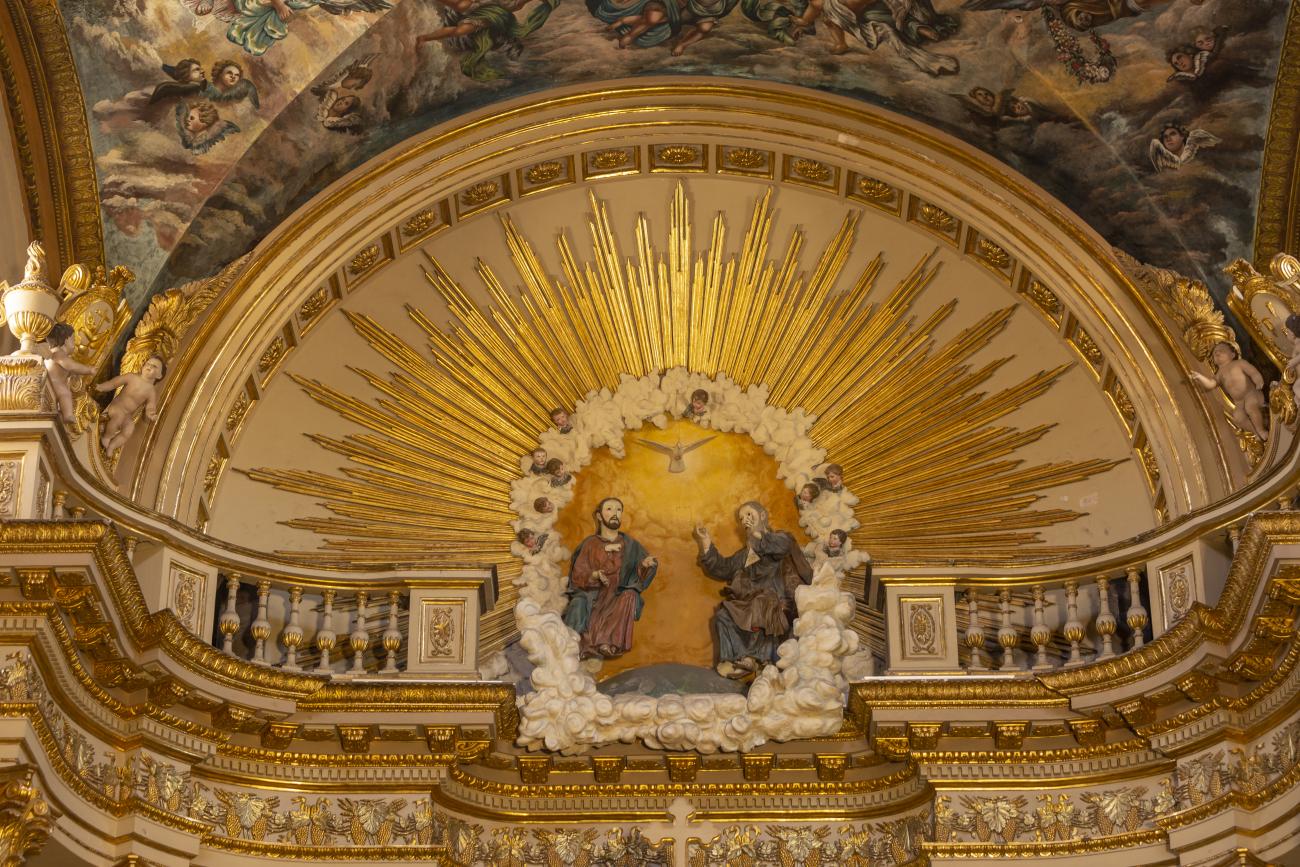

Parroquia del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús "Templo de Santa Clara"

The current temple, built in the late Renaissance style, was consecrated in 1668. On the outside, it has two façades, the first dedicated to Saint Francis and the second to Saint Clare.

Parroquia del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús "Templo de Santa Clara"

The current temple, built in the late Renaissance style, was consecrated in 1668. On the outside, it has two façades, the first dedicated to Saint Francis and the second to Saint Clare. the interior has a single nave, its altarpieces were changed depending on fashion, neglect, and the resources available to the convent (the main altar has been changed more than five times), and it was decorated by famous craftsmen such as Miguel Cabrera, Agustín Ledesma, Tomás Xavier de Peralta, Manuel Pérez de la Serna, Juan Correa, and the architect Francisco Eduardo Tresguerras.

Templo de la Congregación

The decree of October 10, 1671 granted permission to the newly founded Congregation of Secular Clergy of Our Lady of Guadalupe to build a temple dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe. The image was donated by the Hospital of San Hipólito in Mexico City.

Templo de la Congregación

The decree of October 10, 1671 granted permission to the newly founded Congregation of Secular Clergy of Our Lady of Guadalupe to build a temple dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe. The image was donated by the Hospital of San Hipólito in Mexico City. The first stone was laid on June 1, 1675, and the work was completed and dedicated on May 12, 1680. The land was donated by Juan Caballero de Medina, who also contributed his own capital to the construction of the temple, together with his two sons Nicolás and Juan; the latter decorated it with a main altarpiece, the work of the architect of the project, José de Bayas Delgado.

Teatro de la República

A 19th-century building designed by architect Camilo San Germán. Construction began in 1845 on the site where the Alhóndiga (corn exchange) had previously stood. In 1849, funds ran out and the City Council resumed construction, leaving English engineer Tomás Surplice in charge.

Teatro de la República

A 19th-century building designed by architect Camilo San Germán. Construction began in 1845 on the site where the Alhóndiga (corn exchange) had previously stood. In 1849, funds ran out and the City Council resumed construction, leaving English engineer Tomás Surplice in charge. Funds ran out again, and in 1851, actor José Castelán finished financing the construction by requesting the use of the premises for a specified period of time; the work was finally completed in April 1852. On May 2, 1852, it was inaugurated with the comedy “Por dinero baila el perro y por pan si se lo dan” (For money, the dog dances, and for bread, if they give it to him) by Queretaro author José I. de Anievas.

Museo Regional de Querétaro

Since the 16th century, the former Franciscan Convent of Santiago was a huge religious complex that played a role in the daily life of the city's inhabitants and was the seat of the Province of San Pedro and San Pablo de Michoacán.

Museo Regional de Querétaro

Since the 16th century, the former Franciscan Convent of Santiago was a huge religious complex that played a role in the daily life of the city's inhabitants and was the seat of the Province of San Pedro and San Pablo de Michoacán. Throughout the 17th century, the convent underwent intense construction activity and became a religious complex. It reached a total area of approximately 28,000 m², transforming it into a self-sustaining micro-city that, until 1803, trained novices and taught poor children to read and write. After many historical vicissitudes and various uses, such as barracks in armed conflicts during and after the Wars of Reform, as well as some civil and commercial uses, on December 4, 1928, the property was handed over to the state government to establish a Museum of Colonial Religious Art and a School of Arts and Crafts. In 1935, it was handed over to the Ministry of Public Education. In November 1936, the Querétaro Regional Museum was formally handed over to Mr. Patiño, its first director.

Convento de San Agustín

In 1724 and 1726, the need to establish an Augustinian convent in the province of San Nicolás de Tolentino de Michoacán was considered, and on February 8, 1728, the license for its foundation was granted.

Convento de San Agustín

In 1724 and 1726, the need to establish an Augustinian convent in the province of San Nicolás de Tolentino de Michoacán was considered, and on February 8, 1728, the license for its foundation was granted. The residence of Captain Juan Fernández de los Ríos was purchased and adapted for the construction of the convent. On November 28 of the same year, the chapel-oratory was dedicated and opened to the public. The convent was inaugurated on October 2, 1743, and its gatehouse was located where the entrance to the Art Museum is now. The current 19th-century façade was the result of a remodeling to house the Federal Palace. The two-story Baroque cloister is the most spectacular in New Spain; four semicircular arches run around the perimeter of both floors, it has beautiful cornices and pillars with attached herms (on the north and south sides there are Pegasus, lion cubs, elephants, and other zoomorphic figures), and on the keystones of the arches there are scallop shells with the attributes of St. Augustine (pen and inkwell, staff, closed book, open book, heart pierced by two arrows, doctor's cap, mitre, and cardinal's hat) and others with figures from the order's calendar of saints. The spandrels feature Augustinian eagles, the vertical axes are topped with pinnacles, and the keystones of the arches display the sculpted faces of saints from the order. In the center there is a stone fountain with two figures of Roman soldiers. Fray Luis Martínez Lucio was the mastermind behind the iconological and iconographic program, and the executors were the architect Juan Manuel Villagómez together with Indian, mestizo, and Spanish stonemasons, sculptors, and carvers.

Convento Santa Clara

Monastery founded in 1607 by urbanist Poor Clare nuns; their first residence was in a house opposite the Franciscan friars' orchard, and after twenty-six years they moved to this building.

Convento Santa Clara

Monastery founded in 1607 by urbanist Poor Clare nuns; their first residence was in a house opposite the Franciscan friars' orchard, and after twenty-six years they moved to this building. The convent was one of the largest and richest, with an atrium (now the Santa Clara garden), visiting rooms, a profundis room, a refectory, a kitchen, a pantry, an accounting office, work rooms, numerous cells, domestic chapels, an infirmary, an orchard, and other facilities useful to a female monastery. Of the immense convent that covered the current space of three blocks, only the temple, the gatehouse, and the facade of a domestic chapel facing the Guerrero garden remain. After 1864, when the nuns were secularized, the building was divided up and sold to private individuals. Currently, the main cloister is the courtyard of the Federal Judicial Branch, and the rest are residential houses, commercial premises, and a recreational garden.

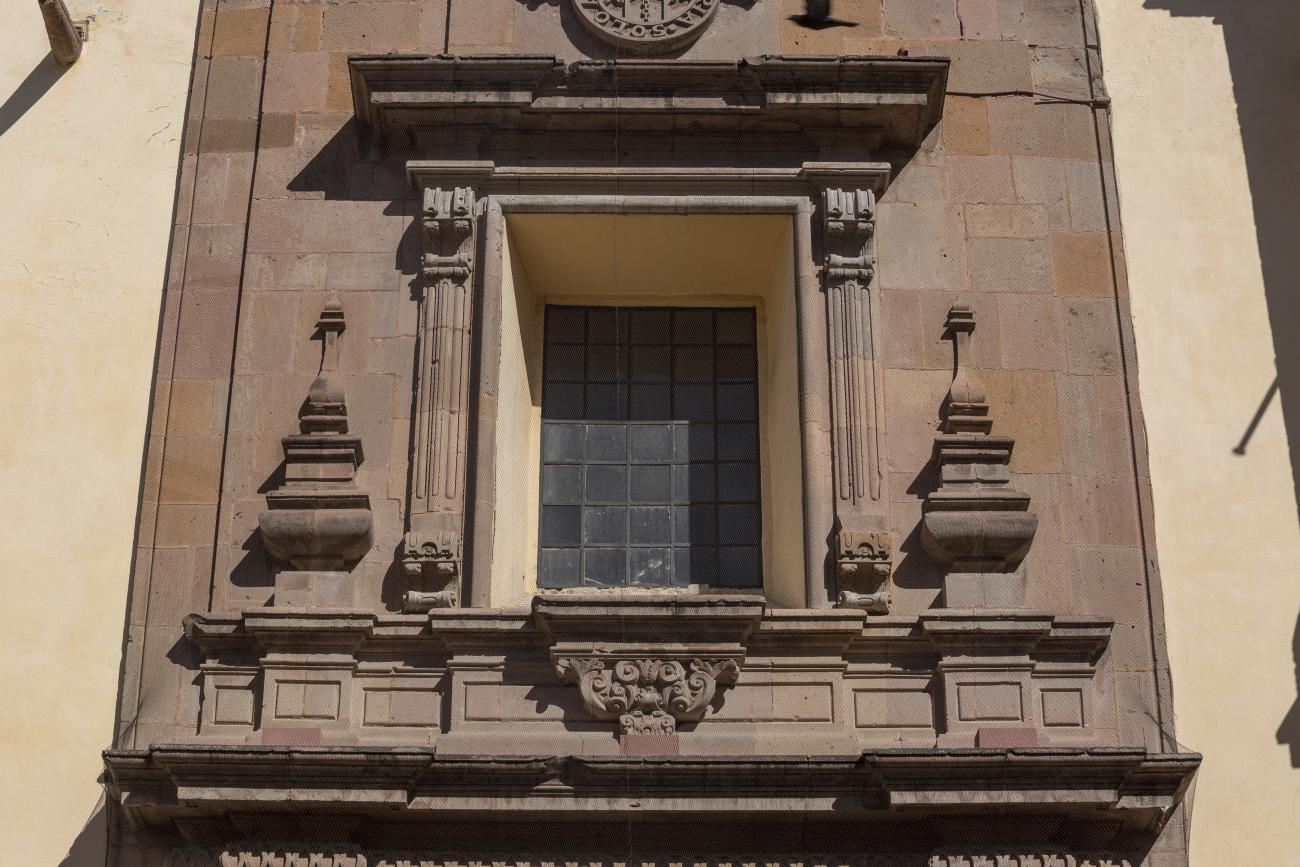

Templo de San Agustín de Ntra. Sra de los Dolores

The first stone of this building was laid on February 2, 1731, and fourteen years later it was dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows. It is distinguished by the luxury of its stone facades and the quality of its ornamental elements.

Templo de San Agustín de Ntra. Sra de los Dolores

The first stone of this building was laid on February 2, 1731, and fourteen years later it was dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows. It is distinguished by the luxury of its stone facades and the quality of its ornamental elements. The pedestals on the first level display the attributes of Saint Augustine: the crozier, the miter, the heart, and the biretta. In the center is a medallion representing the Bishop of Hippo as shepherd and guide of his order. In the niches on the sides are sculptures of Saint Augustine and Saint Francis of Assisi, recognizing them as founders of orders. The second section features sculptures of Saint Rita of Cascia and Saint Clare of Montefalco, prototypes of Augustinian female sainthood. The third level features a monumental crucifix framed with vines, flanked by Saint Joseph, patron saint of the Church of New Spain, and Our Lady of Sorrows, patron saint of this church.

Templo de Santiago (San Francisco)

Construction of this building began between 1550 and 1598, making it the first temple built in Querétaro. The complex consisted of the church, a convent, and a garden that served as a cemetery, as well as other chapels that were demolished during the Reformation.

Templo de Santiago (San Francisco)

Construction of this building began between 1550 and 1598, making it the first temple built in Querétaro. The complex consisted of the church, a convent, and a garden that served as a cemetery, as well as other chapels that were demolished during the Reformation. This church was the Cathedral of Querétaro between 1856 and 1922. In 1934, part of the convent was converted into the Regional Museum of Querétaro.

Templo de San José de Gracia

This 17th-century temple was part of the hospital founded by Conín. The hospital opened in 1586 and served the community for many years. The hospital and temple were dedicated to Saint Joseph and, due to the patronage of the King of Spain, were named the Royal Hospital of Saint Joseph of Grace.

Templo de San José de Gracia

This 17th-century temple was part of the hospital founded by Conín. The hospital opened in 1586 and served the community for many years. The hospital and temple were dedicated to Saint Joseph and, due to the patronage of the King of Spain, were named the Royal Hospital of Saint Joseph of Grace. It was administered by the community until 1624, when it was handed over to the Hippolytes, who renovated the building and built a new church with an altarpiece dedicated to the Immaculate Conception. By 1808, it was no longer sufficient to serve the entire population, and in 1821, the hospital was taken over by civilian doctors.

Parroquia de Santiago

On June 20, 1625, the Society of Jesus established itself in Querétaro after seven years of attempts to obtain a royal license. Both the collegiate body and the temple were named after Saint Ignatius.

Parroquia de Santiago

On June 20, 1625, the Society of Jesus established itself in Querétaro after seven years of attempts to obtain a royal license. Both the collegiate body and the temple were named after Saint Ignatius. In 1659, the coadjutor Tomás Ramírez collaborated in the construction of the temple, not only with funds, but also by directing the work. The temple has a Latin cross plan. To the left of the main façade (facing south) is the only three-section tower (unusual among the Jesuits, who usually had two-section towers). In 1806, a chapel dedicated to La Santa Escala was added to the nave, with a painting of San Antonio signed by Peralta in 1780. In 1696, the construction of another side chapel dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe was commissioned. The interior has been modified on several occasions, from Baroque altars to Art Nouveau decoration. The façade is framed by stone blocks.

Antiguo Colegio Jesuita

This building was constructed in the 17th century as the first Jesuit school. It was built on top of ruins (burials and remains of stone constructions).

Antiguo Colegio Jesuita

This building was constructed in the 17th century as the first Jesuit school. It was built on top of ruins (burials and remains of stone constructions). The building was constructed by the Otomí indigenous people, a fact that is reflected in the arches, cherubs, and quarry fountain found in the Baroque courtyard. The College of San Ignacio was founded on August 20, 1625, and the Jesuits brought with them the pedagogical current of the Renaissance. After the risk of closure due to lack of resources, in 1680 the College was rebuilt and the College of San Francisco Javier was founded, where philosophy, theology, and Latin were taught and a bachelor's degree in arts was awarded. During the second half of the 18th century, both colleges were incorporated into the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico. After the expulsion of the Jesuits, the colleges were left in the hands of the provincial militias, who used them as barracks and stables. In 1869, it was decided that the old colleges would be merged into a Civil College, which was closed at the end of 1950. It currently houses the Faculty of Philosophy of the Autonomous University of Mexico. It forms a complex with the Parish Church of Santiago.

Panteón de los queretanos ilustres