The Southeast

The region comprises southern Mexico and the Yucatan peninsula, as well as Belize, Guatemala and parts of the Central American republics of Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Geographical diversity defined the development and variety of the Mixe-Zoque linguistic groups that inhabited the area through the southern coastal plains of Chiapas and Guatemala, the Guatemalan highlands, the Petén jungle, and the calcareous plains of the Yucatan Peninsula. The study of antiquity in the Southeast has been carried out by dividing it into Highlands and Lowlands, as two differentiated areas where the particularities of the environment allowed the cultural development from 2000 BC until the European conquest.

The Preclassic (2000 BC-150 AD) shows shared cultural features between the inhabitants of the Southeast region and the rest of Mesoamerica, such as agriculture, hunting, fishing and the collection of fruit as forms of subsistence. There are indications that at an early stage the territory could have been divided into various independent political entities, and that, towards the end of this period, between the year 100 and the 250, certain elements appeared, which were to become characteristic of the Mayan culture, such as writing, the calendar, worship of stone monuments and architecture with Mayan vault roofs.

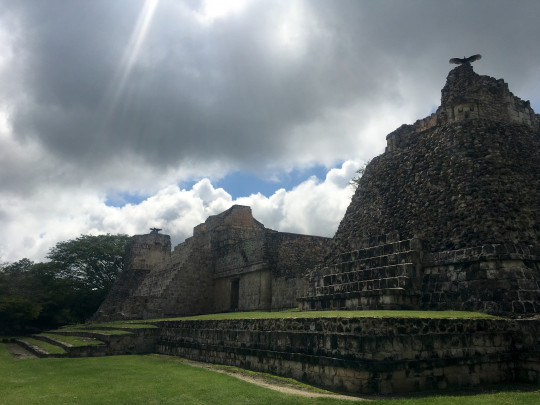

The first cities that were built present temples and palaces around patios or plazas, among which El Mirador, in Guatemala; Calakmul and Edzná, in Campeche; and, Aké and Dzibilchaltún, in Yucatán. In these places the influence of the Olmec culture on mounds and sculptural monuments has been observed.

The period of maximum splendor of the Mayan culture is located in the Classic, between 250 and 900. At this time, numerous city-states with a complex political organization and hierarchical social classes emerge, which allowed the perfecting of the calendar, numbering and writing. The Mayan cities, not only were urban concentrations, but they became centers of production of goods of first necessity and of luxury, as well as of diverse services, that were generated thanks to the control of the natural resources, the knowledge and the population.

In this way, during the Classic, it is possible to find regional capitals, such as Tikal, in the Guatemalan highlands, which competed with Calakmul, in the Petén, for more than a century. In the region of the Usumacinta basin, cities such as Yaxchilán, Palenque and Piedras Negras predominated, although the political, social and economic impulse of the region also allowed the development of other sites, such as Comalcalco, Pomoná, Toniná and Bonampak.

Like other regions of Mesoamerica, the Southeast received the influence of the city of Teotihuacán, and left evidence of this, for example, in the style of the buildings in Tikal, as well as in the architectural element of talud-tablero that is conserved in Dzibilchaltún.

During the late phase of the Classic, between 600 and 900, the consolidation of the power of regional capitals with large urban concentrations favored a war environment, coupled with the establishment of alliances between the group consisting of nobles, warriors and priests. At the same time, the routes and areas of commerce were strengthened, which led to the period of greatest cultural boom and scientific advances, for example in terms of the calculation of time, the use of zero and writing. The influence of the Petén Mayan culture extended to the Yucatan Peninsula, to places such as Cobá, Edzná and Oxkintok, which gave rise to a series of cultural variants that have been identified as the Rio Bec, Chenes and Puuc architectural styles.

The Terminal Classic was the scene of the disintegration of the political and economic centers, as well as contact and commercial exchange with sites on the Gulf Coast and other regions of Mesoamerica, such as El Tajín, Cacaxtla and Xochicalco. There is a greater fusion of Mesoamerican elements in centers such as Chichen Itzá, the Pucc de Uxmal, Kabah, Sayil and Oxkintok, the Chenes of Santa Rosa Xtampak and Edzná.

Several possible factors of decadence have been observed that would lead to the collapse of Mayan culture during the Postclassic in the Southeast (1000-1517), such as natural phenomena, the peasant uprising, the arrival of non-Mayan groups, for example, to Chichen Itza. The increase of the population would have generated a political disorganization and a warlike climate, that would remain until the arrival of the European conquerors.