Yaxchilán

Green stones

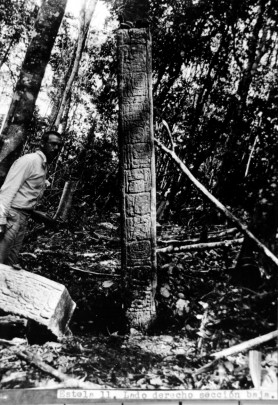

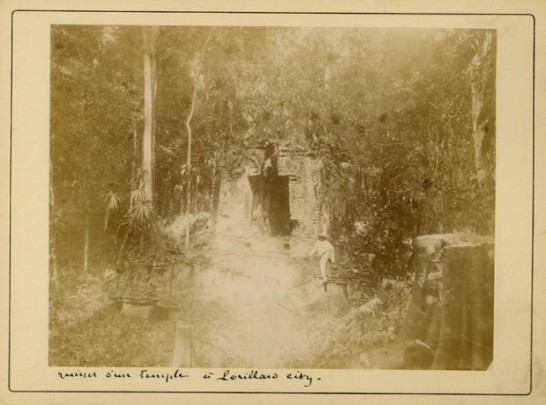

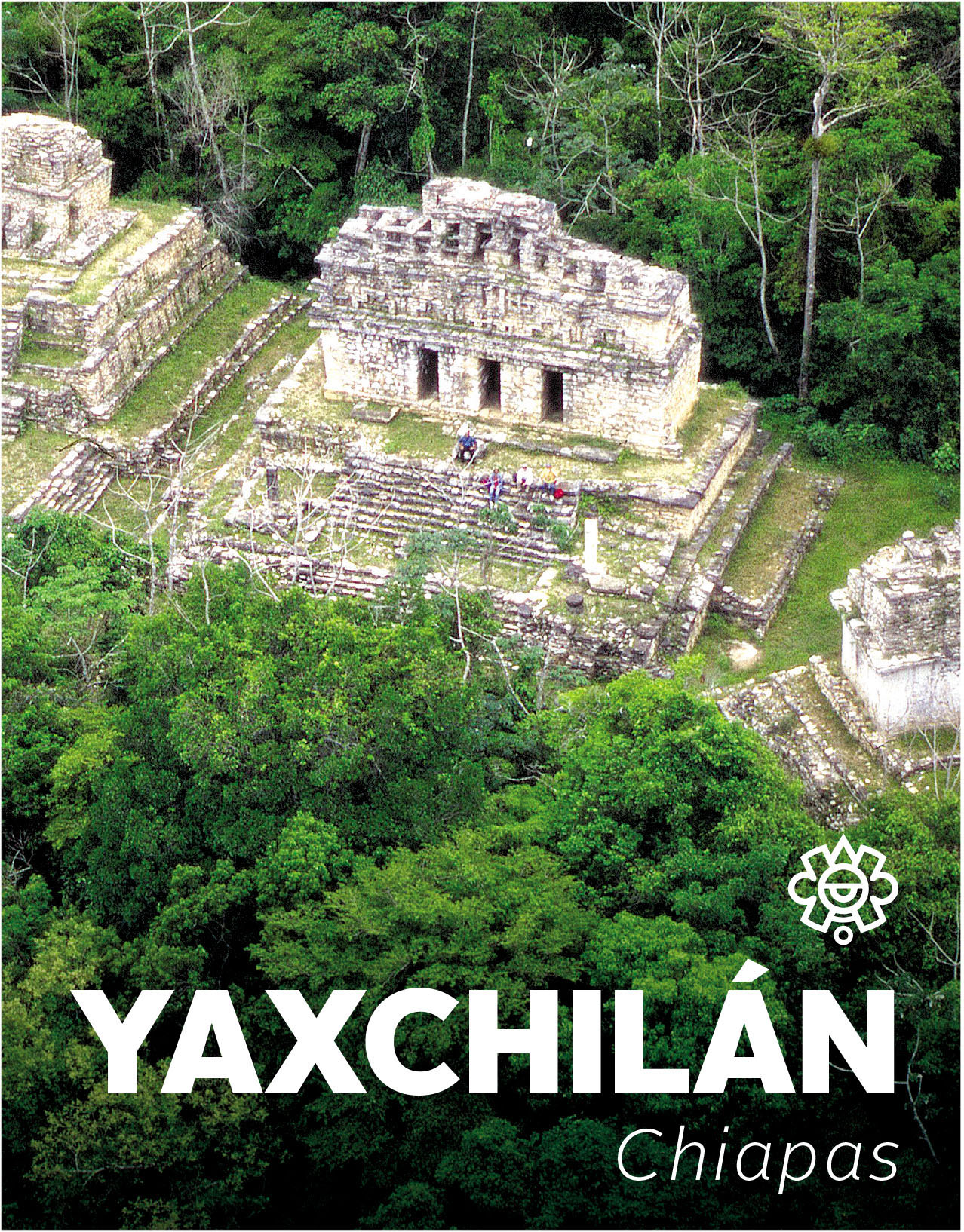

In the Lacandon forest, on the banks of the Usumacinta River, lies this imposing city with beautiful architecture and sculptures. There are 124 remarkable inscriptions on stelae, altars and lintels, recording the acts of its governors, ceremonies, battles, rituals and daily life.

About the site

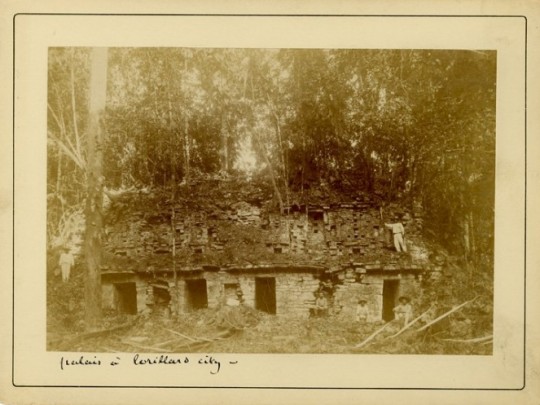

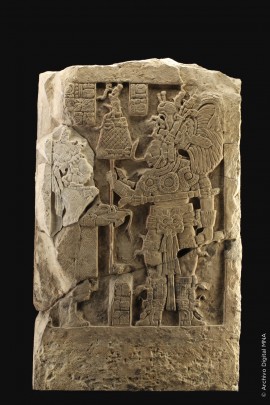

Yaxchilán is one of the most important Mayan archeological sites of the Late Classic period, from 600 to 800 AD. It is especially notable for the richness of more than 130 monuments with inscribed stelae, lintels, altars and steps which tell the story of a dynasty which lasted from the fourth to the ninth centuries. These artistic expressions portray the lives of the governors and scenes of conquest, battle and self-sacrifice.

The site is clearly shaped in response to the river which borders it. The concentration of buildings and civic-religious areas extends from the west to the east on a broad terrace with two important plazas. The people of Yaxchilán made use of the natural contours of the land to build the great majority of the architectural groups, most notably the Great Acropolis, the South Acropolis and the West Acropolis.

The Great Acropolis is located in the center of the site and it includes numerous buildings around two plazas. The western limit is marked by the architectural group consisting of Building 19, also known as the Labyrinth, and buildings 18, 77, 78 and 75, linked by the West Platform. The first section includes a ballcourt and temazcal. The second has another group made up of five structures, one of which could be considered a palace. The third section includes four buildings, two of which contain the earliest substructures of the site. The South Platform of the Great Plaza has six structures, and a great stairway which leads to buildings 25, 26 and 33.

The South Acropolis is located on the hill to the extreme south of the site and is comprised of three buildings (39, 40 and 41), while the West Acropolis, also known as the Small Acropolis, has two plazas and 13 structures and it is situated to the far west of the site, on a natural hill 165 feet above the level of the Great Acropolis plaza.

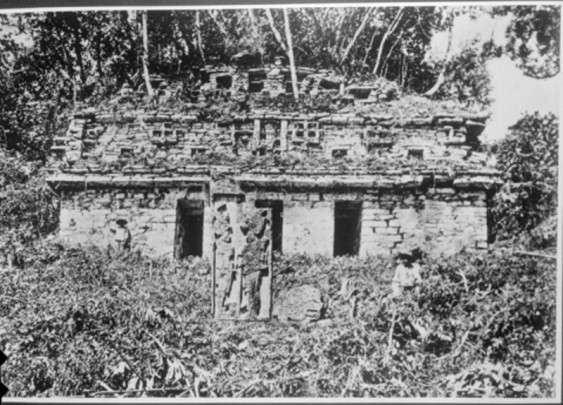

There may be references to Yaxchilán dating from the eighteenth century, but it was not until 1882 when Alfred P. Maudslay and Désiré Charnay arrived at the site that it came to the attention of the western world. Teobert Maler made three journeys to the archeological site in 1895, 1897 and 1900 and he established the names for the buildings and monuments which are still used today; he also gave the site the name we know it by today.

Sylvanus G. Morley made several expeditions and excavations between the years 1914 and 1931. In 1931 Morley carried out research with Karl Ruppert and John S. Bolles, members of the Carnegie Institution of Washington expedition. Bolles’ topographical map is still in use today. The INAH Yaxchilán project began in 1973 under the direction of archeologist Roberto García Moll and by 1985 30 buildings around the Great Acropolis had been excavated and consolidated, with three more in the South Acropolis. The Small (West) Acropolis was excavated between 1989 and 1991 and 13 buildings and their bases were consolidated.

A study analyzing the inscriptions was also carried out. According to this research, the story began in the fourth century when the first records linked to the dynastic sequence of governors appear. The monuments which record the first ten governors of the city were built during the time of Bird Jaguar IV and the possibility must be considered that it was an "official" or fabricated history for the purposes of legitimation.

There was a pause in the dedication of monuments at Yaxchilán and other Mayan sites between 537 and 669. The earliest real historical date on the site: the year 514, appears on stela 27, and it refers to the eleventh governor, Bird Jaguar III. He was succeeded by Shield Jaguar I, Bird Jaguar IV, Shield Jaguar II and Mah k’ina Skull III, whose lives and military exploits were recorded in stone.

One further aspect of note at Yaxchilán is the particularly harmonious combination of cultural heritage and the tropical forest environment. Indeed Yaxchilán is one of the few archeological sites to achieve recognition for both its natural and cultural heritage.

The site is clearly shaped in response to the river which borders it. The concentration of buildings and civic-religious areas extends from the west to the east on a broad terrace with two important plazas. The people of Yaxchilán made use of the natural contours of the land to build the great majority of the architectural groups, most notably the Great Acropolis, the South Acropolis and the West Acropolis.

The Great Acropolis is located in the center of the site and it includes numerous buildings around two plazas. The western limit is marked by the architectural group consisting of Building 19, also known as the Labyrinth, and buildings 18, 77, 78 and 75, linked by the West Platform. The first section includes a ballcourt and temazcal. The second has another group made up of five structures, one of which could be considered a palace. The third section includes four buildings, two of which contain the earliest substructures of the site. The South Platform of the Great Plaza has six structures, and a great stairway which leads to buildings 25, 26 and 33.

The South Acropolis is located on the hill to the extreme south of the site and is comprised of three buildings (39, 40 and 41), while the West Acropolis, also known as the Small Acropolis, has two plazas and 13 structures and it is situated to the far west of the site, on a natural hill 165 feet above the level of the Great Acropolis plaza.

There may be references to Yaxchilán dating from the eighteenth century, but it was not until 1882 when Alfred P. Maudslay and Désiré Charnay arrived at the site that it came to the attention of the western world. Teobert Maler made three journeys to the archeological site in 1895, 1897 and 1900 and he established the names for the buildings and monuments which are still used today; he also gave the site the name we know it by today.

Sylvanus G. Morley made several expeditions and excavations between the years 1914 and 1931. In 1931 Morley carried out research with Karl Ruppert and John S. Bolles, members of the Carnegie Institution of Washington expedition. Bolles’ topographical map is still in use today. The INAH Yaxchilán project began in 1973 under the direction of archeologist Roberto García Moll and by 1985 30 buildings around the Great Acropolis had been excavated and consolidated, with three more in the South Acropolis. The Small (West) Acropolis was excavated between 1989 and 1991 and 13 buildings and their bases were consolidated.

A study analyzing the inscriptions was also carried out. According to this research, the story began in the fourth century when the first records linked to the dynastic sequence of governors appear. The monuments which record the first ten governors of the city were built during the time of Bird Jaguar IV and the possibility must be considered that it was an "official" or fabricated history for the purposes of legitimation.

There was a pause in the dedication of monuments at Yaxchilán and other Mayan sites between 537 and 669. The earliest real historical date on the site: the year 514, appears on stela 27, and it refers to the eleventh governor, Bird Jaguar III. He was succeeded by Shield Jaguar I, Bird Jaguar IV, Shield Jaguar II and Mah k’ina Skull III, whose lives and military exploits were recorded in stone.

One further aspect of note at Yaxchilán is the particularly harmonious combination of cultural heritage and the tropical forest environment. Indeed Yaxchilán is one of the few archeological sites to achieve recognition for both its natural and cultural heritage.

Map

Did you know...

- Before Teobert Maler called it Yaxchilán, the site had received different names: Menché, Menché-Tinamit and Villa Lorillard.

- The sculpture on which Bird Jaguar IV is sitting, in Building 33, was beheaded in the 19th century, and the Lacandon people believe that, when the head returns to its original position, the celestial jaguars will swallow all living beings and with that the world will end.

- Stela 35, located inside Building 21, has a cavity that still preserves the smoked remains of the original carbon used by the pre-Hispanic Mayans.

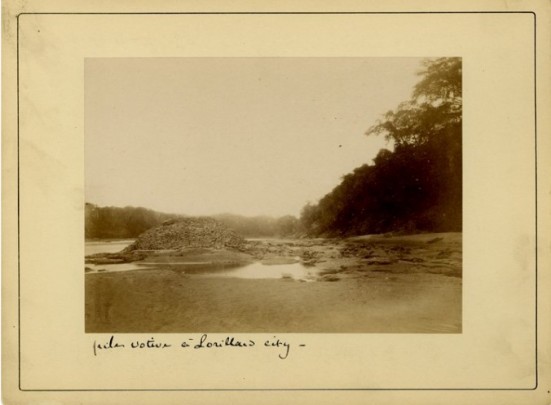

- The stone mound built on the river bank is completely preserved despite the intense currents of the river. It could be the base of a bridge or a pier.

- Building 19, known as "The Labyrinth," has a series of underground corridors that lead to small rooms; one of these passages is still sealed and no one knows where it leads.

An expert point of view

Akira Kaneko

Centro INAH Chiapas

-

+52 (916) 345 2705

Directory

Subdirectora de la Zona Arqueológica

Keiko Teranishi Castillo

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (916) 345 2721