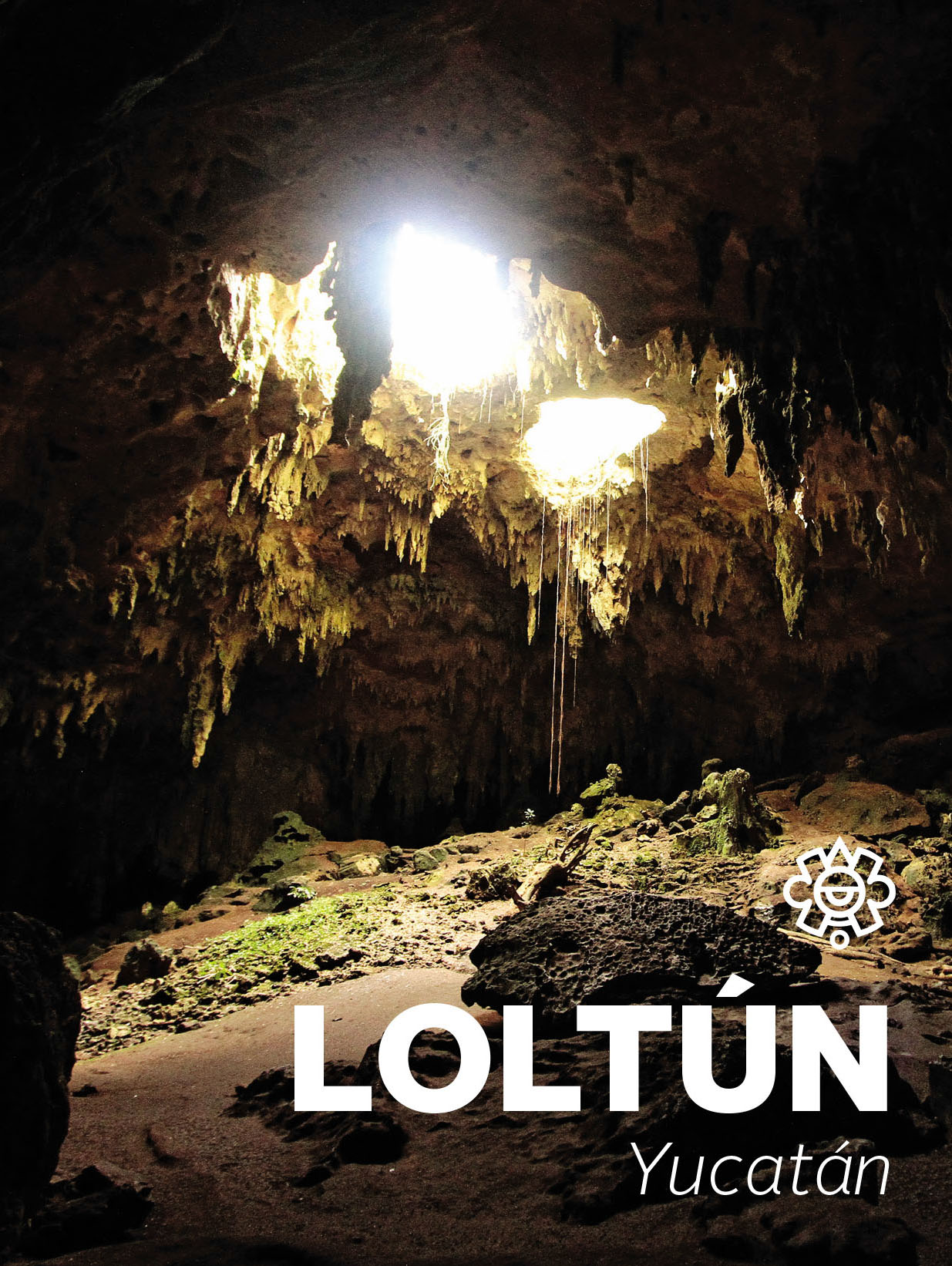

Loltún

Stone flower

These caves provide a fascinating experience. Galleries and natural formations, with stone paintings and carvings, allow visitors a vision of primitive people in the region, and the domestication of plants and animals, until they became sedentary. The site dates back to 9000 BC.

About the site

To date the Loltún caves have the longest chronological sequence of any site discovered in the north of the Yucatan peninsula. The evidence found in these caves suggests that they were used as an encampment in earliest times and then subsequently as a dwelling place. The process of occupation began towards 9000 BC with material remains showing from the early presence of man in this region. The caves’ occupation ran parallel to the domestication of plants and animals and up to the incorporation of architectural design and sculpture into everyday life, illustrating the development of society from nomadic to settled living. From the Classic period the caves ceased to be used as dwellings and it is only certain that they were used for water storage. Other important features are the 145 mural paintings and the 42 petroglyphs found to date. The caves were used most intensively in the Late Preclassic period from 400 to 200 BC.

In 1886 and 1892, Teoberto Maler, a well-known Mayan scholar born in Italy of German parents, visited Loltún and made a few prints and paintings of what he found inside the cave. Shortly afterwards, between 1888 and 1891, the US archeologist and diplomat Edward H. Thompson undertook excavations at Loltún financed by the Peabody Museum of Harvard University. Thompson, who was working as the United States vice-consul, was also behind the dredging of the sacred cenote of Chichen Itza. In 1895, Henry C. Mercer of the University of Pennsylvania visited 29 caves and excavated 10 in the Puuc mountain range with the aim of studying the social and anatomical development of man in the Americas, but he failed to find caves of similar antiquity to those in Europe. Into the twentieth century, the first map of the caves was made by Jack Grant and Bill Dailey, and they discovered the sculpture known as the Loltún Head.

The first excavations by the INAH were carried out in 1978, under the guidance of archeologist Ricardo Velázquez Valadez. The material found in the explorations of the 1970s and 1980s revealed that the Loltún cave had been occupied as far back as 9000 BC, and that at that time the cave must have been an abundant source of natural resources used by groups of hunter gatherers, as evidenced by the finds: stone material with possible marks of wear, pictorial motifs and bone remains of now extinct fauna. This important evidence positions Loltún as a unique cave in northern Yucatan, with archeological finds from the archaic period.

The cave provided suhuy ha’ (virgin water) for everyday use and divination ceremonies, clay for making pots and stone as a raw material. It was a place of veneration and offerings.

In 1886 and 1892, Teoberto Maler, a well-known Mayan scholar born in Italy of German parents, visited Loltún and made a few prints and paintings of what he found inside the cave. Shortly afterwards, between 1888 and 1891, the US archeologist and diplomat Edward H. Thompson undertook excavations at Loltún financed by the Peabody Museum of Harvard University. Thompson, who was working as the United States vice-consul, was also behind the dredging of the sacred cenote of Chichen Itza. In 1895, Henry C. Mercer of the University of Pennsylvania visited 29 caves and excavated 10 in the Puuc mountain range with the aim of studying the social and anatomical development of man in the Americas, but he failed to find caves of similar antiquity to those in Europe. Into the twentieth century, the first map of the caves was made by Jack Grant and Bill Dailey, and they discovered the sculpture known as the Loltún Head.

The first excavations by the INAH were carried out in 1978, under the guidance of archeologist Ricardo Velázquez Valadez. The material found in the explorations of the 1970s and 1980s revealed that the Loltún cave had been occupied as far back as 9000 BC, and that at that time the cave must have been an abundant source of natural resources used by groups of hunter gatherers, as evidenced by the finds: stone material with possible marks of wear, pictorial motifs and bone remains of now extinct fauna. This important evidence positions Loltún as a unique cave in northern Yucatan, with archeological finds from the archaic period.

The cave provided suhuy ha’ (virgin water) for everyday use and divination ceremonies, clay for making pots and stone as a raw material. It was a place of veneration and offerings.

9000 a.C. - 1500

Preclásico a Posclásico

400 a.C. - 200

Preclásico Medio a Preclásico Tardío

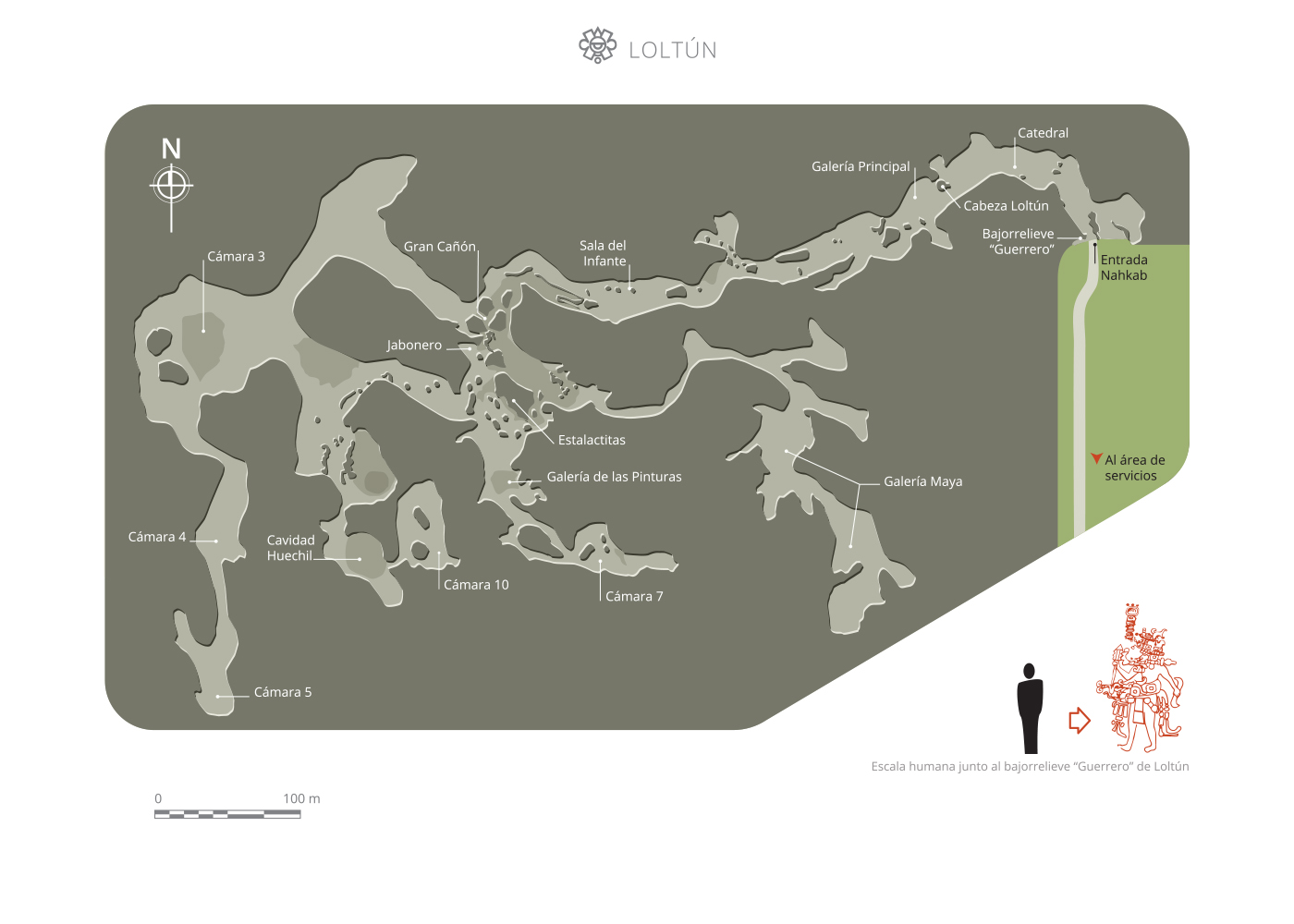

Map

Did you know...

- The remains of Pleistocene fauna have been found at Loltún.

- The earliest human settlement in the Yucatan peninsula was at Loltún.

- Man inhabited this cave before plants were domesticated.

Practical information

Temporarily closed

Monday to Sunday from 8:00 to 17:00 hrs

$75.00 pesos

$75.00 pesos

Se localiza a 110 km al sur de Mérida, Yucatán.

From the city of Merida, take Federal Highway 180 towards Campeche by the longer route; in Ticul follow Federal Highway 184 southwest towards Oxkutzcab, and the site is 6 km ahead.

-

+52 (999) 944 4068

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Directory

Director de la Ruta Pucc

José Guadalupe Huchím Herrera

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (997) 976 2064