Palenque

Fortified houses

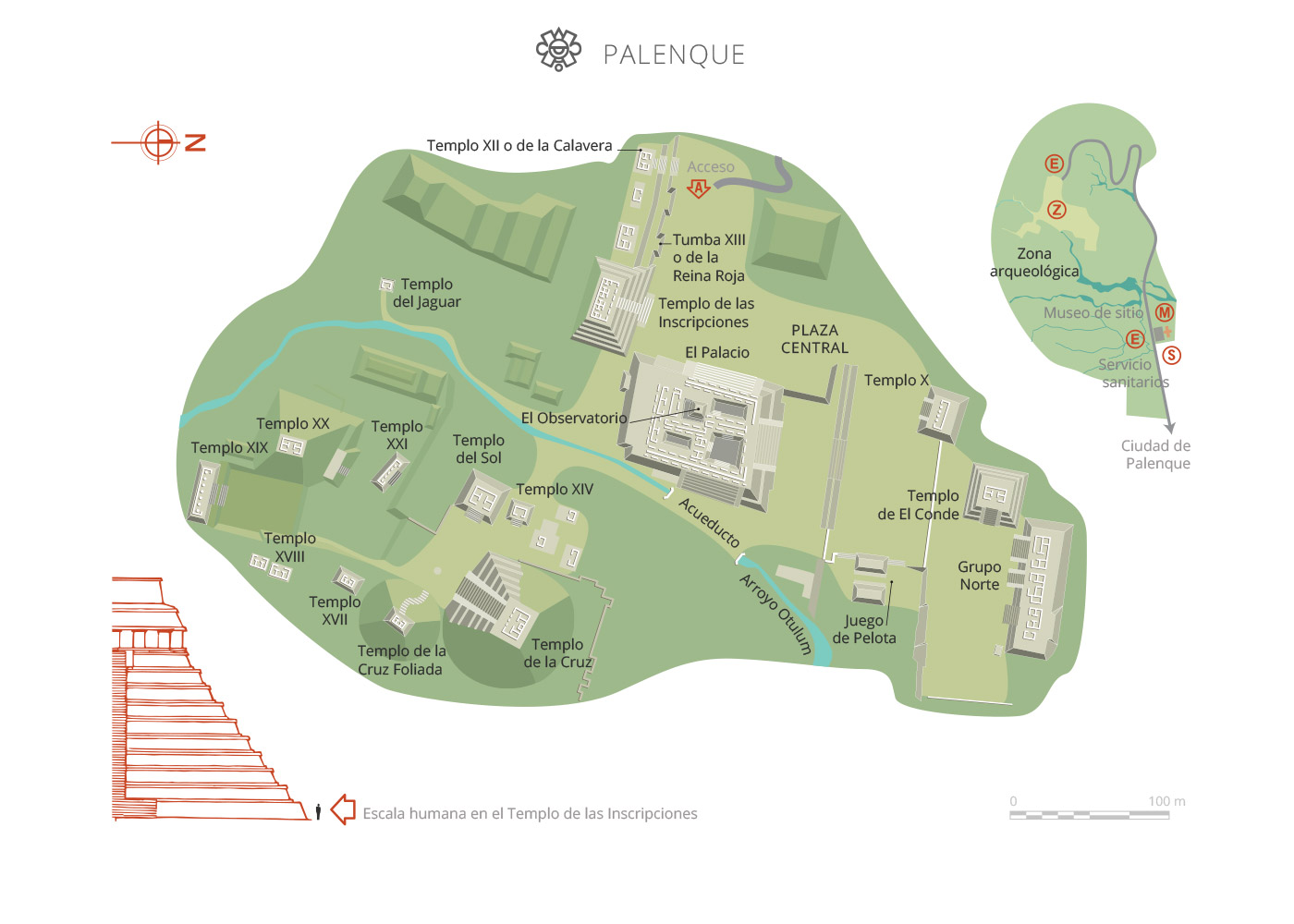

A dazzling city (400 – 900 AD), it lay hidden in the jungle for many centuries, and was the seat of the powerful dynasty of king Pakal. It is home to fabulous temples, palaces, plazas, tombs, sculptures, and hieroglyphic inscriptions telling the history of the place. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987.

About the site

Palenque was one of the most important cities in the Mayan region during the Classic period from 250 to 900 AD. Originally, this site was a village of farmers and hunters, which eventually became the capital of a powerful dynasty dominating an extensive region. Construction of the buildings in the central area of the city began around the year 431, as did intensive long distance trade. Textual analysis shows that nine male governors and two women ruled between 345 and 603. It is reckoned that Palenque reached its peak between 615 and 783. The platforms, ceremonial groups, plazas, palaces, aqueducts, mausoleums and residential units are all reflections of the city’s power. These architectural groupings allow us to make deductions about the politico-administrative, ritual or residential functions of this great city. It is believed that around the year 800 it had a population of close to 8,000. Thereafter the city began to decline and it was abandoned a century later, without evidence of a clear reason for its fall.

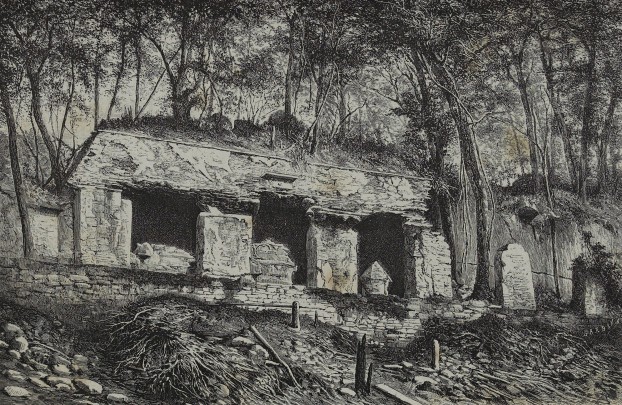

At the end of the eighteenth century, the first European to publicize the existence of Palenque appears to have been Canon Ramón Ordóñez y Aguiar, a priest in the Royal City of Chiapas, now known as San Cristóbal de Las Casas. His great-uncle Antonio de Solís had been the first Spaniard to visit Palenque in around 1730, but the fact only came to light 40 years later when Ordóñez told several people about it. Among those he told was Esteban Gutiérrez, who travelled to the site in 1773; Fernando Gómez de Andrade, the mayor of the Royal City, also went, as did Tomás Luis de Roca, the Prior Provincial of the Dominicans. In turn, they all informed José de Estachería, president of the Audiencia of Guatemala, who ordered the first official exploration that would lead to Palenque opening up to the western world. In 1784 Estachería ordered the lieutenant José Antonio Calderón, residing in the new town of Palenque, to carry out the first inspection visit of the pre-Hispanic city. In his report Calderón told of his three-day journey in heavy rain guided by the local indigenous people. When he received Calderón’s report, Estachería ordered Antonio Bernasconi, the architect of royal works in Guatemala, to set out with José Calderón on a new expedition to the site in 1785.

Several plans and drawings were made of the buildings, as well as sketches of the reliefs modeled in stucco. At the end of 1786, King Carlos III ordered the investigation of the native cultural remains to continue. Since Bernasconi had died, Estachería commissioned Captain Antonio del Río to undertake the task at Palenque. Del Río reached the city at the end of 1787 accompanied by the draftsman Ricardo Armendáriz. In his report he tells of how he cleared and burnt the undergrowth with the help of 79 Indians, as well as carrying out various excavations of the buildings, perhaps the first methodical excavations reported at the site.

The era of explorers and romantic travelers began at the start of the nineteenth century, and the wild imagination of the eighteenth century visitors was replaced with a more realistic understanding of the pre-Hispanic city. Nevertheless, unsystematic excavations led to the destruction of context and the loss of artifacts to foreign museums.

This stage began with the journey of Captain Guillermo Dupaix and the draftsman Guillermo Castañeda in 1805, sent by Carlos IV to explore the south of New Spain. His reports and drawings were forgotten about, as the War of Independence broke out very shortly afterwards. Upon his departure Dupaix took one of the three stones which make up the Tablet of the Cross, which was later returned to the Mexican government by the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. The report by Dupaix, who was possibly the first identifiable looter in Palenque, was not published until 1934.

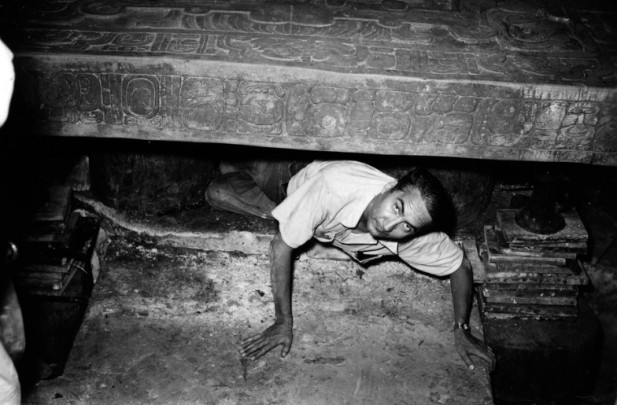

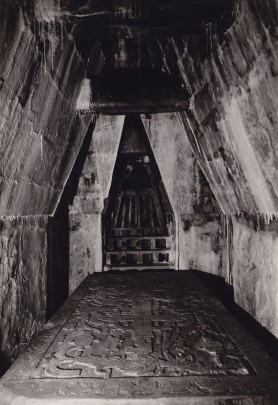

Excavations continued and in 1952 the archeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier discovered the Temple of the Inscriptions, the rich and revealing tomb of the great lord Pakal (K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, “radiant janaab bird standard bearer”), the most notable and sensational in Mexican archeology for many years.

At the end of the eighteenth century, the first European to publicize the existence of Palenque appears to have been Canon Ramón Ordóñez y Aguiar, a priest in the Royal City of Chiapas, now known as San Cristóbal de Las Casas. His great-uncle Antonio de Solís had been the first Spaniard to visit Palenque in around 1730, but the fact only came to light 40 years later when Ordóñez told several people about it. Among those he told was Esteban Gutiérrez, who travelled to the site in 1773; Fernando Gómez de Andrade, the mayor of the Royal City, also went, as did Tomás Luis de Roca, the Prior Provincial of the Dominicans. In turn, they all informed José de Estachería, president of the Audiencia of Guatemala, who ordered the first official exploration that would lead to Palenque opening up to the western world. In 1784 Estachería ordered the lieutenant José Antonio Calderón, residing in the new town of Palenque, to carry out the first inspection visit of the pre-Hispanic city. In his report Calderón told of his three-day journey in heavy rain guided by the local indigenous people. When he received Calderón’s report, Estachería ordered Antonio Bernasconi, the architect of royal works in Guatemala, to set out with José Calderón on a new expedition to the site in 1785.

Several plans and drawings were made of the buildings, as well as sketches of the reliefs modeled in stucco. At the end of 1786, King Carlos III ordered the investigation of the native cultural remains to continue. Since Bernasconi had died, Estachería commissioned Captain Antonio del Río to undertake the task at Palenque. Del Río reached the city at the end of 1787 accompanied by the draftsman Ricardo Armendáriz. In his report he tells of how he cleared and burnt the undergrowth with the help of 79 Indians, as well as carrying out various excavations of the buildings, perhaps the first methodical excavations reported at the site.

The era of explorers and romantic travelers began at the start of the nineteenth century, and the wild imagination of the eighteenth century visitors was replaced with a more realistic understanding of the pre-Hispanic city. Nevertheless, unsystematic excavations led to the destruction of context and the loss of artifacts to foreign museums.

This stage began with the journey of Captain Guillermo Dupaix and the draftsman Guillermo Castañeda in 1805, sent by Carlos IV to explore the south of New Spain. His reports and drawings were forgotten about, as the War of Independence broke out very shortly afterwards. Upon his departure Dupaix took one of the three stones which make up the Tablet of the Cross, which was later returned to the Mexican government by the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. The report by Dupaix, who was possibly the first identifiable looter in Palenque, was not published until 1934.

Excavations continued and in 1952 the archeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier discovered the Temple of the Inscriptions, the rich and revealing tomb of the great lord Pakal (K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, “radiant janaab bird standard bearer”), the most notable and sensational in Mexican archeology for many years.

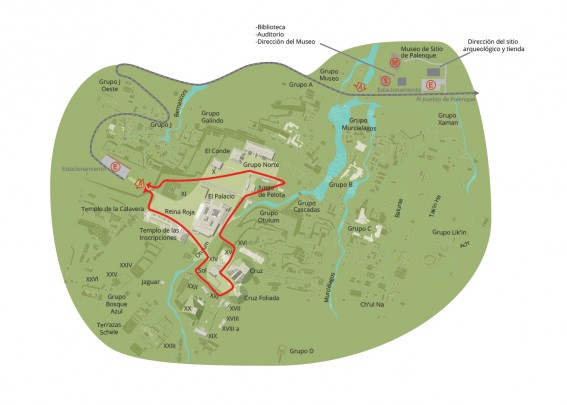

Map

Did you know...

- The abundant deposits of limestone around the city provided the raw material for the construction of buildings, the preparation of stucco and the creation of texts and images that decorated the interior of the temples, as well as for the manufacture of utensils for daily use, such as metates and mortars.

- Like other Mayan cities, Palenque had a political organization at the state level, with a ruler (Ajaw) supported by nobles of different rank, counselors and religious specialists who guided the city's destiny.

- On June 13, 1952 one of the most important discoveries in the archeology of Palenque took place. Excavations inside the Temple of the Inscriptions located one of the most imposing funeral tombs of Mayan royalty. Inside a beautifully decorated sarcophagus were the mortal remains of K'inich Janaab 'Pakal who, as the epigraphic records have revealed, was the eleventh ruler of Palenque, reigning between 615 and 683 AD.

An expert point of view

Arnoldo González Cruz

Centro INAH Chiapas

Practical information

Monday to Sunday from 08:30 to 17:00 hrs. Las entry 16:00 hrs.

$91.00 pesos

https://ventadeboletosenlinea.inah.gob.mx

Se localiza a 8 kilómetros del municipio de Palenque, en el estado de Chiapas.

Services

Directory

Subdirectora de la Zona Arqueológica

Keiko Teranishi Castillo

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (916) 345 2721