Pátzcuaro

Historical Monuments Zone

Abstract

Founded by Bishop Vasco de Quiroga in the 16th century, Pátzcuaro was the most important city in Michoacán at the beginning of the viceregal era. Its cobbled streets and squares surrounded by red-tiled adobe buildings are the perfect setting for one of Mexico’s most precious traditions: the celebration of the Day of the Dead.

The name Pátzcuaro comes from the Tarascan word petáhzacua or patahzácuaro which is interpreted as a site of cúes or temples, and refers to the many buildings of this type. The region where this city is located is of great importance due to its geographical conditions, its humid temperate climate, abundant vegetation, fauna and water resources. The natural environment of Lake Pátzcuaro has enabled the settlement of human groups since pre-Hispanic times, and the development of economic activities such as fishing, hunting, gathering and agriculture.

The earliest antecedent of the city is a pre-Hispanic settlement dating back to the 14th century. In this place Tariácuri was born, a ruler under whose leadership the Tarascan or Purépecha empire emerged and consolidated. It was at its peak when the Spanish arrived.

In the 16th century, Pátzcuaro was founded as a city on the initiative of Don Vasco Vázquez de Quiroga, appointed first bishop of Michoacán in 1537. There he established, during the first half of the 16th century, the capital of the province of Michoacán, the seat of the bishopric and the “Real y Primitivo Colegio de San Nicolás,” one of the oldest educational institutions in the country. Vasco de Quiroga, known fondly by the natives as “Tata Vasco,” founded the Hospital de Santa Martha, thereby establishing a new form of socio-economic organization. He also introduced innovative agricultural practices, and diversified the trades and crafts practiced by the inhabitants.

The arrival of Spanish residents in Pátzcuaro began in the year 1538, when Vasco de Quiroga moved the episcopal see from Tzintzuntzan to Pátzcuaro, bringing with him 29 Spanish families. Tata Vasco also embarked on an ambitious project to build a cathedral with an innovative design with five radiating naves. It was never completed but the layout appears in the city’s coat of arms. In 1580, the ecclesiastical and civil powers were formally transferred to the city of Valladolid, the new capital of Michoacán. Pátzcuaro continued with its slow and peaceful growth over the following centuries.

In the 18th century there was a period of economic boom in the city that allowed the formation of a powerful group of criollos and peninsular Spaniards who controlled the trade and exploitation of the copper mines located in the vicinity. This group held important political positions and enjoyed great social prestige, which was reflected in the construction of sumptuous houses located around the main square. These mansions stand out for their Baroque style with exterior ornaments in pink cantera stone on the columns and arches that define the porticoes, as well as on the facades: on the entrance doorways, the window frames and the balconies.

The location of Pátzcuaro on the main trade routes boosted activities such as tanning, blacksmithing, and the establishment of inns and other businesses. With the arrival of the railroad at the end of the 19th century these activities decreased and, beginning in the first decades of the 20th century, the city began to acquire fame as a tourist destination, largely due to the preservation of its traditional way of life and its architecture that still retains its unity thanks to a building tradition that has been passed down from generation to generation. This is based on the use of local materials such as adobe, stone, wood, and clay tiles for the roofs.

One of the important characteristics of Pátzcuaro is the generosity of its open spaces, public gardens and plazas, as well as the importance of its private courtyards and gardens. Most of the open spaces were laid out during the 19th century, a period when the contemporary fashion for gardens dictated the use of French styles. As a result, open spaces that previously lacked gardens were laid out according to new criteria. The layout of the city is still marked by the old royal road and adapts to the topography, with rectangular blocks that are more regular close to the main square and more irregular on the periphery.

Figures involved in the main national political events of the 19th and 20th centuries also lived in Pátzcuaro. One such figure during the independence movement was Gertrudis Bocanegra de Lazo de la Vega, who died defending the ideals of freedom together with her husband and children. During the War of Reform and the French intervention, Pátzcuaro was the scene of struggles where Manuel García Pueblita won fame, known today as a martyr of the Republican cause. The final battle against the French intervention in the State of Michoacán also took place in this city. Meanwhile, during the Mexican Revolution, Pátzcuaro was the scene of the Battle of June 16, 1918, won by the federal army.

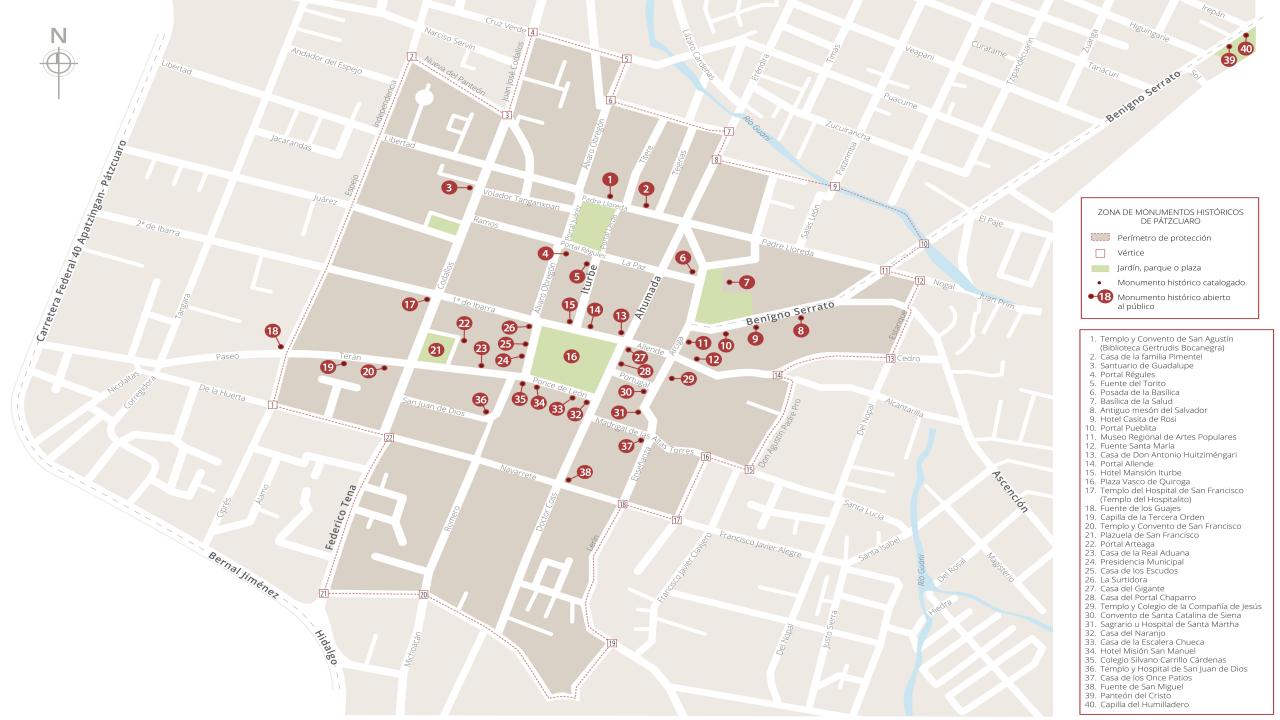

Pátzcuaro was declared a Zone of Historical Monuments by presidential decree on December 19, 1990, with an area of 0.89 square kilometers. It is made up of 42 blocks that comprise more than 300 buildings with historical value built between the 16th and 19th centuries.

The religious buildings include the monastery complexes of San Agustín, of the Dominican nuns of Santa Catarina, today known as the House of the Eleven Courtyards; of San Juan de Dios; of San Francisco; of the Society of Jesus; and of the Tabernacle. Also of note are the Basilica of Our Lady of Health and the Priests’ House; as are the churches of the Hospital and of the Third Order, the shrine of Guadalupe, and the chapels of Humilladero, Calvario and Santa Catarina.

Other notable buildings that were originally intended for educational and welfare purposes and for the use of civil authorities are the City Hall; the former Royal Houses; the former Royal Customs House; and the former Colegio de San Nicolás. The large open spaces resulting from the urban changes that took place between the 17th and 20th centuries are also significant: the Vasco de Quiroga or Main Plaza; the Gertrudis Bocanegra or Small Plaza; the Revolución Plaza in the San Francisco neighborhood; the Plaza del Santuario located on one side of the church dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe; the Plazuela de las Tenerías; the plazas of La Basílica, of El Volador, of San Juan de Dios, of Calle del Rostro and of the Society of Jesus. Also of note are the old cemetery and the El Cristo cemetery.

There are also civil buildings for private use of notable architectural value, such as the house of Don Antonio Huitzimengari; the house of Doña Juana Pavón de Morelos; the house where the teacher Narciso Servín García was born; the House of the Small Door; the House of the Giant; the house where the insurgent Gertrudis Bocanegra was born; the house of Manuel Abarca de León, where José María Abarca lived, who participated in the Conspiracy of Valladolid of 1809; the mansion of Don Tomás de Casas Navarrete; the former house of the Venicia family; the house of Don Francisco Arias; as well as the former inns of San Cristóbal, of San Juan de Dios, of El Ángel and of San Antonio.

The city’s hydraulic infrastructure is visible in the wells, many of which are associated with local legends, such as the Well of San Miguel, the Well of the Bull, the Guajes Well and the Santa María Well, also known as the fountain of Vasco de Quiroga, where according to tradition the bishop made water flow with his staff.

Today Pátzcuaro is the most important city in the basin of the lake of the same name, and a center for tourism and crafts in Michoacán. One of the typical local traditions is the veneration of the Virgin of Health: this is a sculpture made of cane paste that was commissioned by Tata Vasco in 1539 and displays an image of the Immaculate Conception that became associated with health thanks to its miraculous healing of the sick.

Meanwhile, the celebration of the Day of the Dead is one of the most iconic traditions of Pátzcuaro and of the other towns located around the lake of the same name, as well as on the island of Janitzio. For the All Saints’ festival, Pátzcuaro becomes a setting for concerts and cultural events in the squares and on the streets; the local inhabitants go to spend the night in the cemeteries to visit their loved ones and decorate their graves with orange marigold and purple cockscomb flowers, candles and all kinds of other items as offerings.

“The indigenous festivities dedicated to the dead,” of which the ceremonies of Michoacán are part, was inscribed in 2008 on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage (originally declared in 2003).

Biblioteca Gertrudis Bocanegra

This building was inaugurated in 1576 as the Augustinian convent of Santa Catalina Virgen y Mártir. At the beginning of the 17th century, it was adorned with an altarpiece and a new roof, as well as ornaments in the sacristy.

Biblioteca Gertrudis Bocanegra

This building was inaugurated in 1576 as the Augustinian convent of Santa Catalina Virgen y Mártir. At the beginning of the 17th century, it was adorned with an altarpiece and a new roof, as well as ornaments in the sacristy. Between 1670 and 1679, Prior Fray José Morales devoted himself to improving the temple until it became one of the best in the city, although it remained one of the poorest. Between 1697 and 1706, a second floor was added to house the monks. In the mid-18th century, it was rebuilt with capital from the convent's chaplaincies. However, a few years after its construction, some of its walls were already cracked. In 1882, the building was transferred to the city council and divided into several lots. In 1936, architect Alberto Le Duc and engineer H. Gómez converted the convent into a theater. The temple was designated for use as a public library.

Casa de los Once Patios

Museo de Artes e Industrias Populares

In 1540, Bishop Vasco de Quiroga founded the San Nicolás Obispo Seminary College for young Spaniards in this building, where indigenous people were taught free of charge. This college, the oldest on the continent, was moved to Valladolid in 1580.

Museo de Artes e Industrias Populares

In 1540, Bishop Vasco de Quiroga founded the San Nicolás Obispo Seminary College for young Spaniards in this building, where indigenous people were taught free of charge. This college, the oldest on the continent, was moved to Valladolid in 1580. The Baroque façade was built in the 18th century, and an arcade was added to the courtyard. In 1869, it was established as a School of Arts and Crafts, and a year later, this school was taken over by the city's artisans. In the second half of the 20th century, the building was restored to adapt it to its new function as the Regional Museum of Popular Arts, which exhibits textiles, ceramics, lacquerware, and masks from the region.

Presidencia Municipal

Plaza San Francisco

Plaza Vasco de Quiroga

16th-century square

Portal de Allende

Templo El Sagrario

Templo de San Francisco de Asís

This building was the fifth Franciscan convent in the Province of Michoacán, established by Friar Martín de Jesús in the mid-16th century. The church and convent had a cemetery in front, and to the south there was an orchard and a plot of land protected by a stone fence, 365 varas long.

Templo de San Francisco de Asís

This building was the fifth Franciscan convent in the Province of Michoacán, established by Friar Martín de Jesús in the mid-16th century. The church and convent had a cemetery in front, and to the south there was an orchard and a plot of land protected by a stone fence, 365 varas long. Vegetables and provisions were grown there to supply the community. During the 18th century, several repairs were made and the convent was roofed with tiles. The convent was largely rebuilt in 1904 by Friar Buenaventura Chávez and served as a dwelling for the Franciscans until 1915.

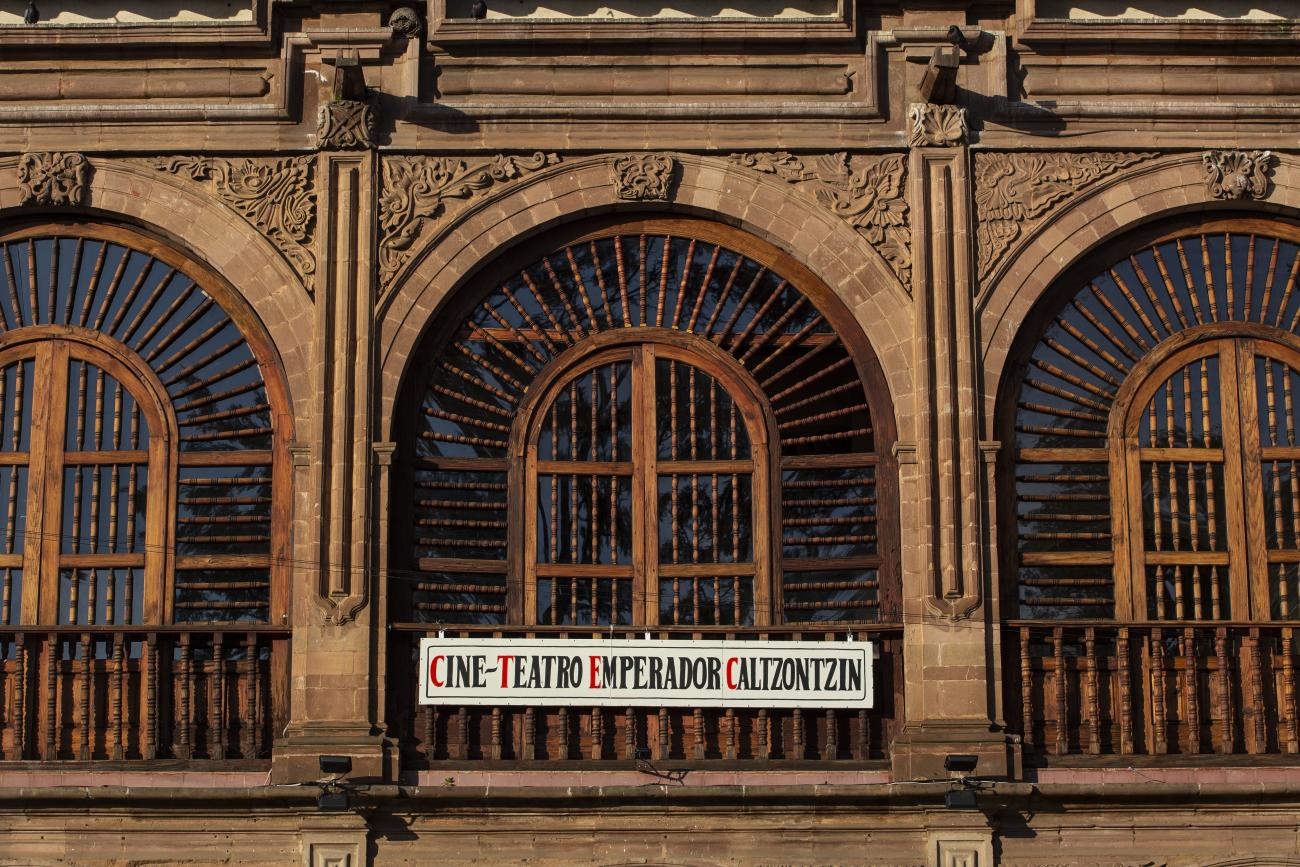

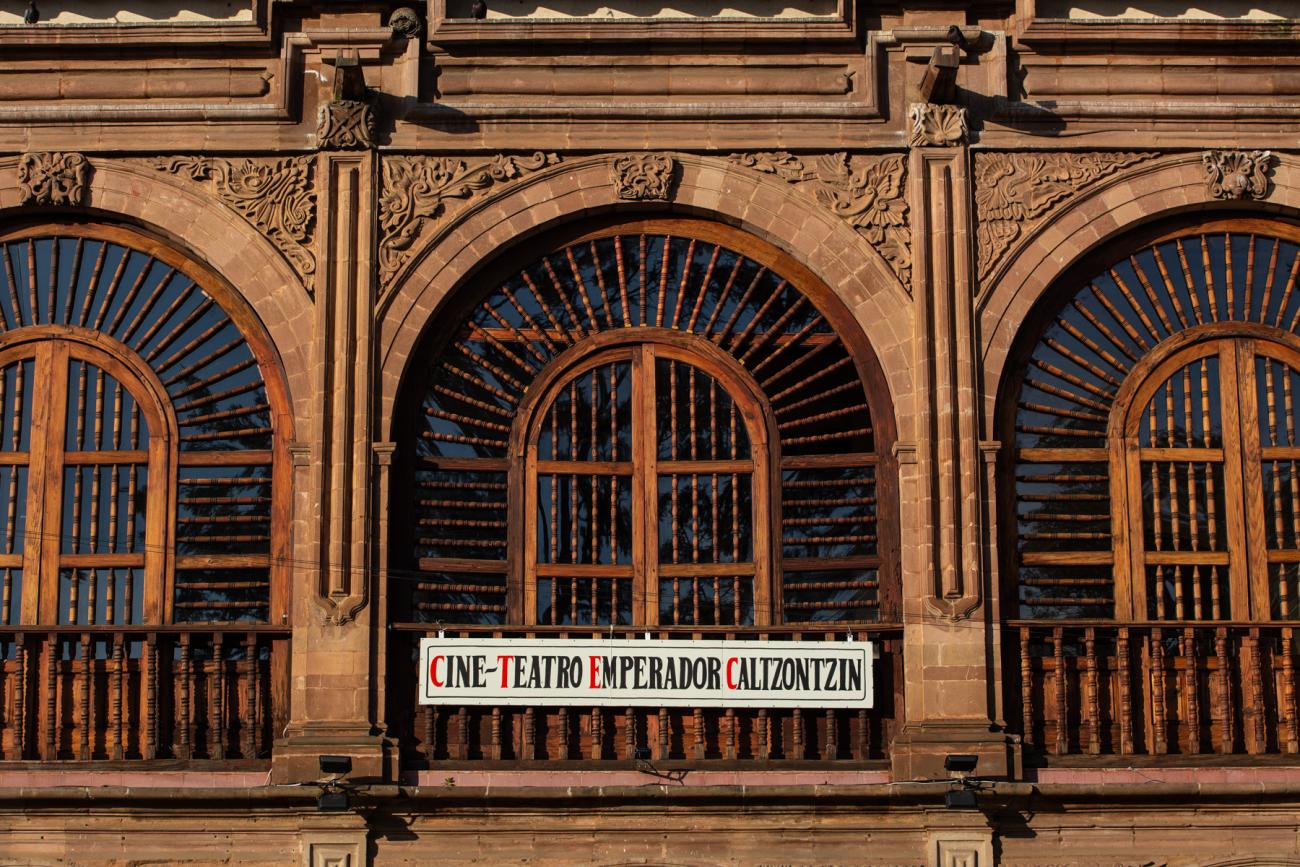

Teatro Emperador Caltzontzin