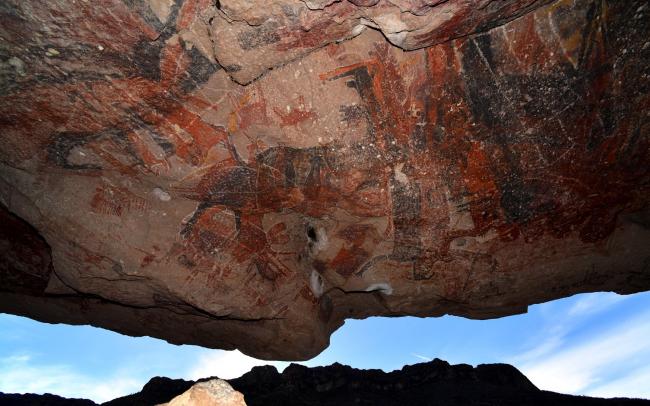

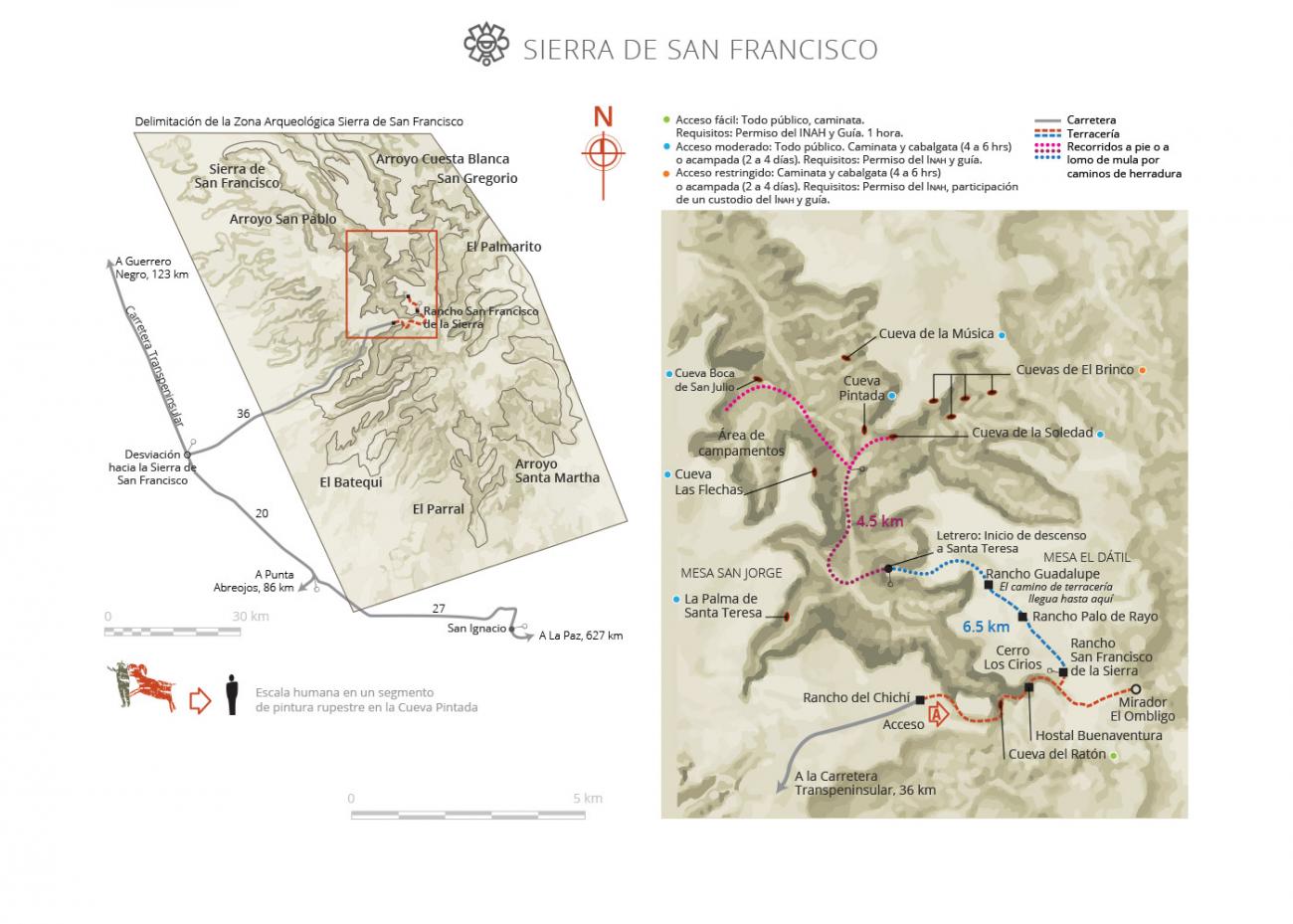

It is perhaps the cave with the most extraordinary examples of rock art in the Sierra de San Francisco. The cave is one of the largest in the sierra with a dimension of 175 m from one end to the other. The good preservation of the murals is remarkable, as well as the density of the superimposed layers in some of the panels. It is possible that the paintings reflect the physical, social and cultural environment of their creators.

There are no historical sources that explain the process of creation of these murals, there are only some references on the part of the chroniclers that relate that, when the natives were questioned about the origin of the paintings, they referred to a legend transmitted from parents to children, according to which many years ago, fleeing from the north, a race of giants had arrived to the region. A part of them continued towards the south following the coast and the others went into the mountains and were the authors of the paintings.

Likewise, the paintings manifest certain symbolic associations between the different representations, which occur through superimposition. Even the deliberate placement of one design on top of another could imply a ritual action at the time of painting, a phenomenon that is obvious in La Pintada Cave, especially in the first set of images, where human, zoomorphic, abstract and composite figures are profusely mixed; in some cases, this relationship is harmonious and dynamic. The paints were prepared with natural pigments; the red, orange and yellow colors were obtained from iron oxides, very abundant in the area; the black is manganese oxide and the white pigment is gypsum, properly speaking. The pigments were reduced to powder in metates or mortars, which can still be seen inside the cave, and an agglutinant was added to give them consistency and allow their application. This formula was so successful that it has allowed their permanence at the site, as well as the extraordinary preservation of the color.

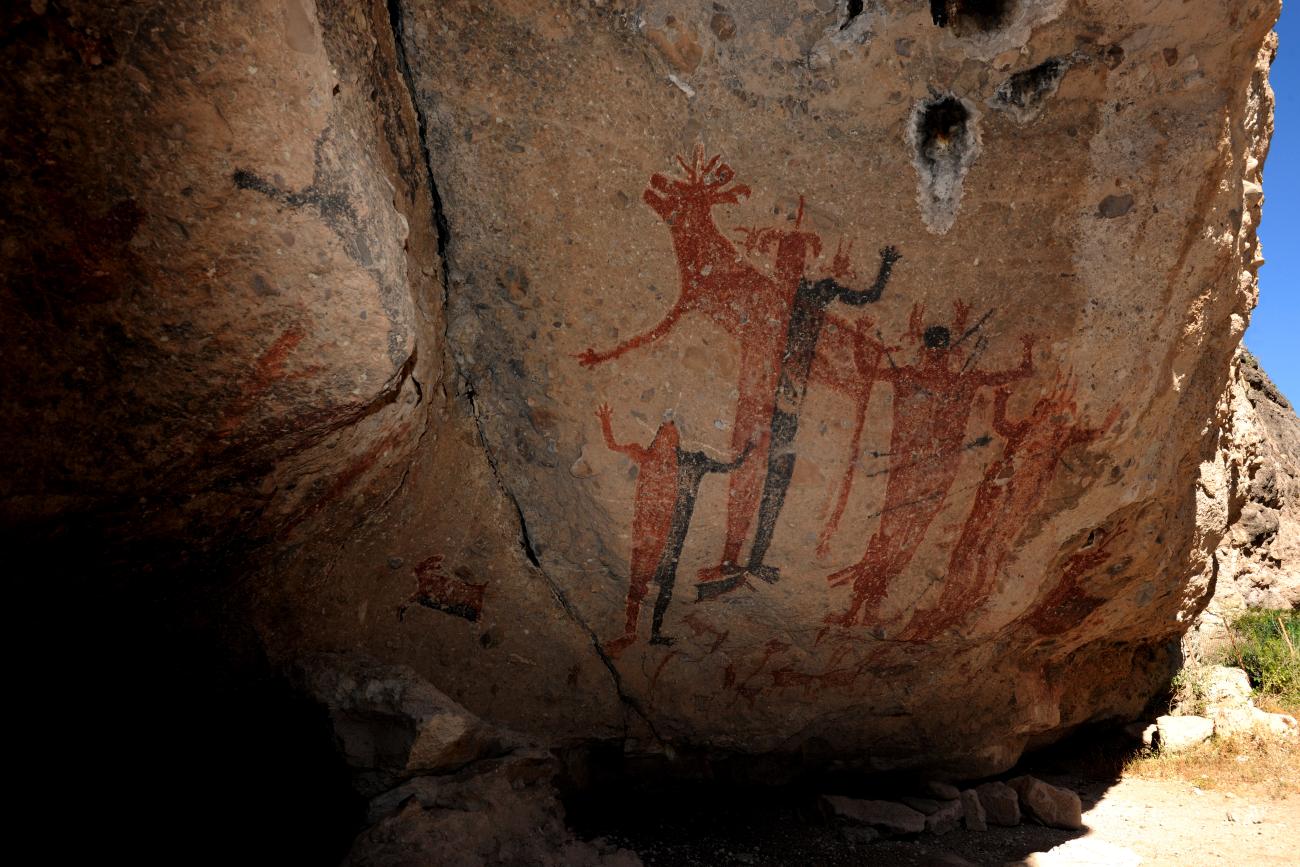

The second of the panels of La Pintada Cave is at a considerable height, a reason for speculation regarding the difficulty involved in its elaboration, which suggests the great skill of the authors, who were also excellent stone workers, weavers of cords and nets of agave, palm and datilillo fibers; they worked ornaments of shell, bone and wood, so it is to be assumed that they could have built scaffolding, ladders or any other structure that allowed them to reach the highest parts of the caves.

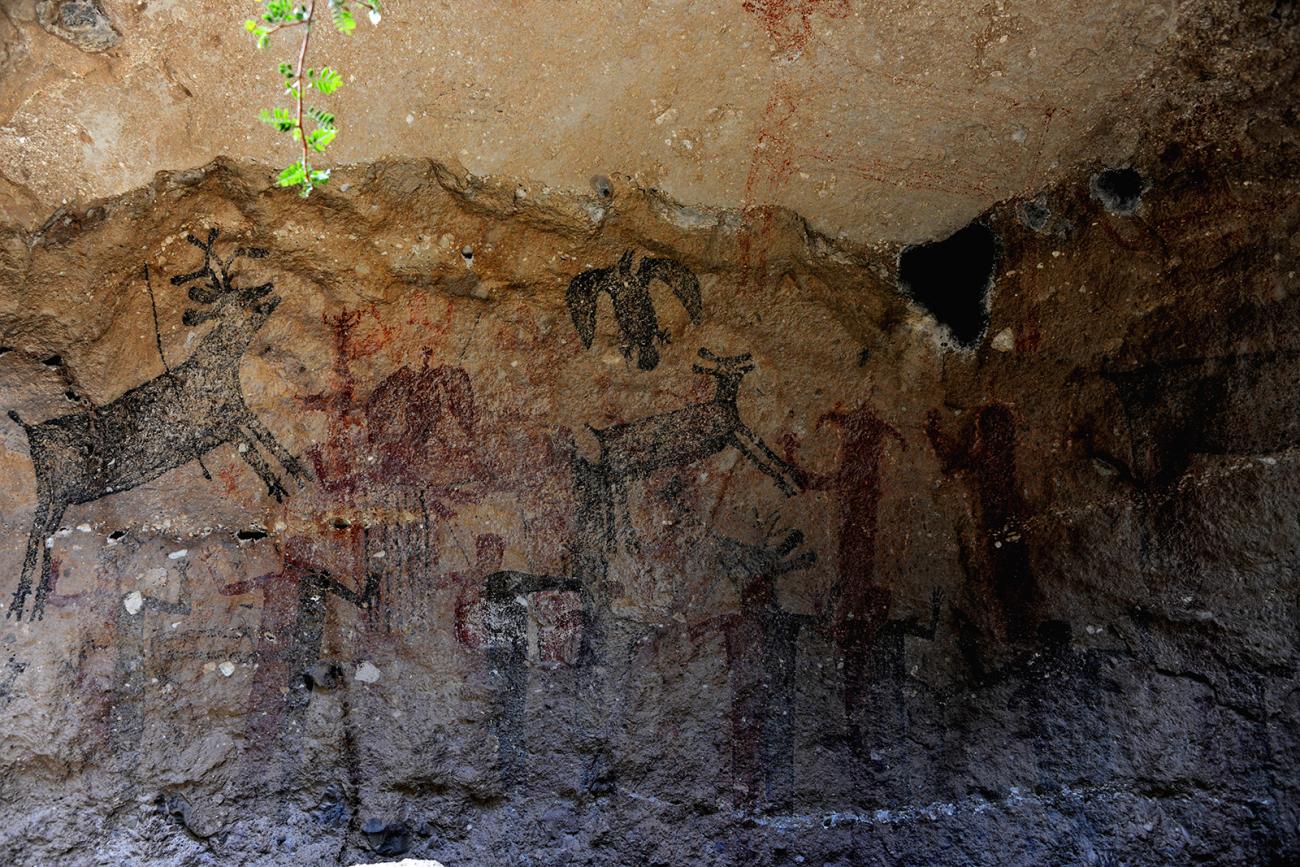

The last panel of the cave is very unique due to the distribution and balance of the forms, as well as the representation of the designs. There is a group of human and animal figures, almost all life-size. Also striking is the figure of an enormous marine animal, apparently a composite animal, half whale, half seal. A peculiar aspect of the group is the use of natural reliefs to enhance special characteristics in human and animal forms, such as the representation of pregnancy in a female human figure. Some figures wear plumes or headdresses, which gives them a certain identity, and perhaps represent sorcerers, shamans or group leaders, as the chronicles of the first missionaries describe headdresses similar to those observed.

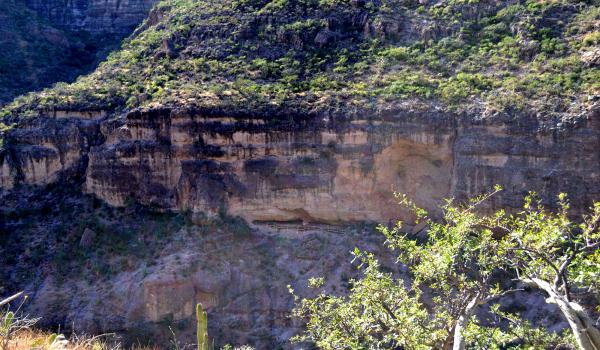

Panoramic view: Panoramic view of La Pintada Cave, Sierra de San Francisco. The oasis of Cañón de Santa Teresa and its palm grove can be seen.

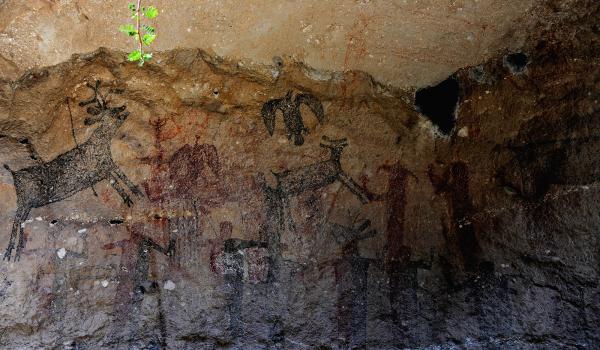

Sector of the central panel: A sector of the central panel of La Pintada Cave. It highlights a deer with the body painted in black and yellow and two birds in flight, apparently vultures. The intense overlapping of figures can be appreciated.

Central Panel: Not all the Great Mural paintings are of great dimensions; it includes some small ones as it is appreciated in this group of two birds, a human figure and a rabbit. The scale measures 10 cm.

East end panel: Panoramic view of the rock panel located at the east end of La Pintada Cave. These figures are of enormous dimensions, even larger than life size.

Detail of the panel at the east end: Detail of the cave panel at the east end of La Pintada Cave. In the center of the composition are a male and a female bighorn sheep.

Composite animal: One of the most enigmatic figures in La Pintada Cave. It is a composite animal: the upper part corresponds to a whale, the lower part to a seal. Some authors claim that it is a representation of a seal.

Detail of the panel at the east end: Detail of the rock panel at the east end of La Pintada Cave. Male and female fused with a red male deer; the abdomen of the deer was designed taking advantage of the protuberance of the stone support. The women are distinguished by the breasts designed below the armpits.