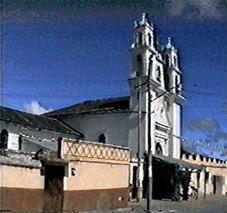

Comitán de Domínguez

Historical Monuments Zone

Abstract

The oldest city in Chiapas, the cradle of independence in that state and birthplace of Belisario Domínguez, who opposed the usurping government of Victoriano Huerta during the Mexican Revolution. Its colonial architecture, its Santo Domingo monastery and its San Caralampio festival give the city its own unique stamp.

Formerly known as Balún Canán and later called Comitlán by the Mexica people, meaning “place of potters”, this city is located on the edges of the Central Highlands of the state of Chiapas. In pre-Hispanic times this territory was occupied by the Tzeltales, who established an intense trading and cultural exchange with the peoples of central Mexico. In 1486, the city was subjugated by the Mexica.

In 1528 Comitán was explored by Pedro de Portocarrero, sent by the conquistador of Guatemala, Pedro de Alvarado. Later the territory was granted to Diego de Olguín as an encomienda. The colonization of Comitán was formally commenced in the year 1556 when the Dominican friars and a group of indigenous Tojolabales, led by missionary Diego Tinoco, moved the population of Comitán to the site where it is currently located.

However, there is a legend that says that a group of Spaniards and indigenous people were exploring the region when they discovered the trail of a lion, which they followed to hunt it. The tracks led them to a fountain that flowed between the rocks, from which the lion drank. The Spanish respected the life of the animal and decided to settle in that place. Later, a monumental fountain was built with a statue of a lion, which is preserved today in the square in the La Pila neighborhood.

The Dominican friars, in addition to evangelizing the natives, influenced the urbanization of the town. The construction of the Santo Domingo de Guzmán monastery, patron of the city, was carried out between the 16th and 17th centuries. Its architecture is a clear example of the influence of the Mudejar style in the region.

The name of the city has undergone several changes, in 1625 it was named the town of Santo Domingo de Comitán and on October 29, 1813 the courts of Cádiz, Spain, granted it the title of Ciudad de Santa María de Comitán. Between 1542 and 1821, Comitán belonged to the Audiencia de los Confines, based in Guatemala City, whose jurisdiction included: Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Guatemala and Chiapas. This meant that Chiapas was not part of the Audiencia of Mexico.

One of the most significant events in the history of Comitán occurred in the context of the struggle for independence. Father Fray Matías de Córdoba Ordóñez, parish priest of the San Sebastián neighborhood, addressed the town, urging it to seek independence from the Spanish crown. After obtaining the support of his parishioners, he went to the Town Hall where an open council meeting was held at which Fray Matías insisted on the importance of drafting an official letter stating the declaration of independence. It is said that thanks to the support of Josefina García and other women who exerted pressure on the men present at the meeting, it was possible to convince the people to fight for independence and to draft the official letter declaring the independence of Comitán. This happened on August 28, 1821. A few days later, on September 3, the independence of the province of Chiapas was declared.

When the independence of Mexico was declared and the first Mexican empire was established under the command of Agustín de Iturbide, Chiapas was annexed to it. Later, in 1823, when Central America separated from Mexico, Chiapas did so too, however, in 1824 it was definitively reintegrated into the Mexican Republic. During the Porfiriato period the landowners and ranchers of Comitán enjoyed a boom time. This led to some of the best-preserved historical buildings in the city being built.

In the revolutionary era, the most significant episode was the intervention of Belisario Domínguez, a Mexican politician from the city who, as a senator of the republic for the state of Chiapas, denounced before the National Congress the illegitimacy of the government of Victoriano Huerta, an action that cost him his life. In honor of his bravery, on November 21, 1934, the surname Domínguez was added to the name of his hometown, making it the city of “Comitán de Domínguez”.

Another important character in the history and culture of our country who lived in Comitán is the writer and poet Rosario Castellanos, considered one of the most important Mexican writers of the 20th century. Although she was born in Mexico City in 1925, she spent her childhood in Comitán.

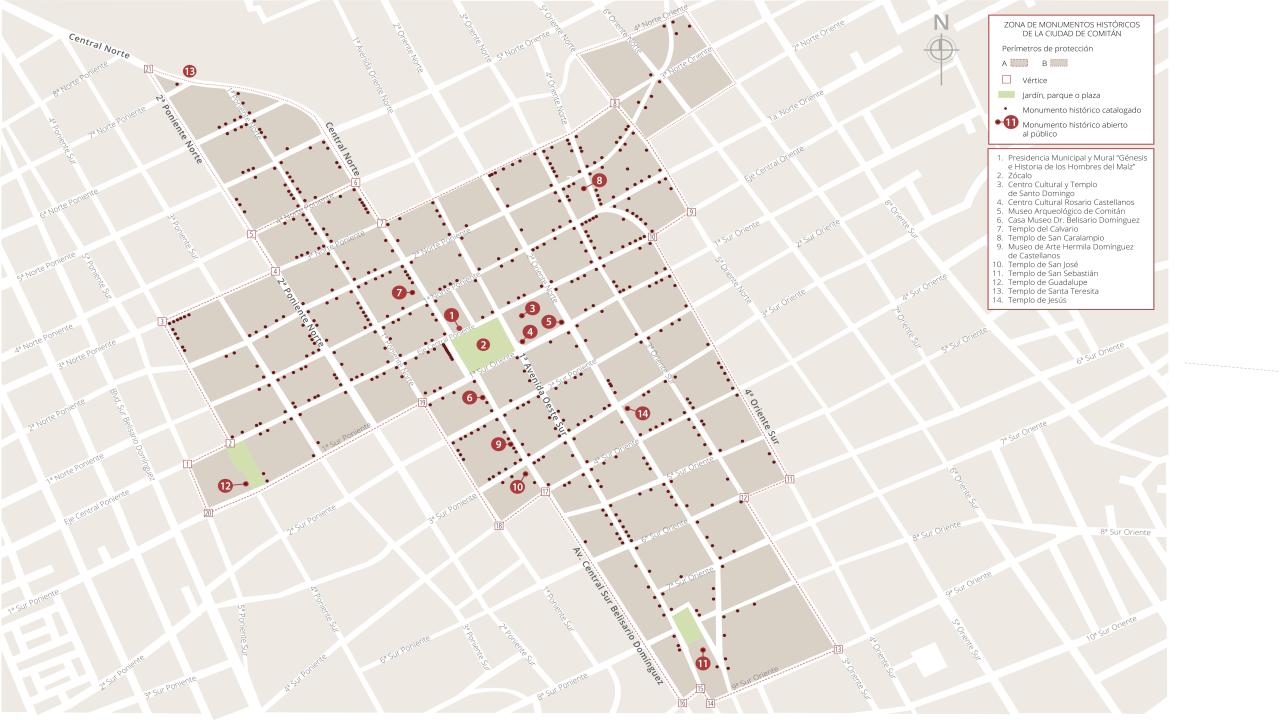

In the mid-20th century, Comitán began a gradual process of growth that turned it into a center of economic, administrative and political activity, favored by its geographical location. Today it enjoys a high level of regional social and economic development, as the fourth largest city in the state. Likewise, it is distinguished by its beautiful colonial appearance, notably the wooden colonnades that form unique spaces for visitors to stroll.

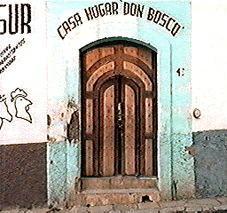

One of its main traditions is the festival in honor of San Caralampio that takes place from February 10 to 20. According to tradition, the martyr Saint Caralampio (Asia Minor, 89-202 AD) cured the population of the plague that occurred in 1852. For this reason, every year on February 10, a pilgrimage is held in honor of the saint. The Church of San Caralampio was completed in 1868 in a Neoclassical style.

Comitán was declared a Zone of Artistic and Historical Monuments in 2000 and in September 2012 it was designated a Pueblo Mágico (Magical Town) by the Ministry of Tourism. The zone of historical monuments has an area of 1.12 km2 and it is made up of 84 blocks that comprise 243 historical buildings, some dedicated to religious worship such as: the Former Monastery of Santo Domingo, and the churches of San Caralampio, San José, Guadalupe, San Sebastián, Calvario and Jesús.

The city preserves the urban layout of the 16th century, set on a hillside with a series of sloping streets located around the Central Plaza. Its urban landscape is made up of single-story buildings with the outline of religious buildings emerging above them, integrated into the natural landscape of the Comitán Valley with its mountainous surroundings.

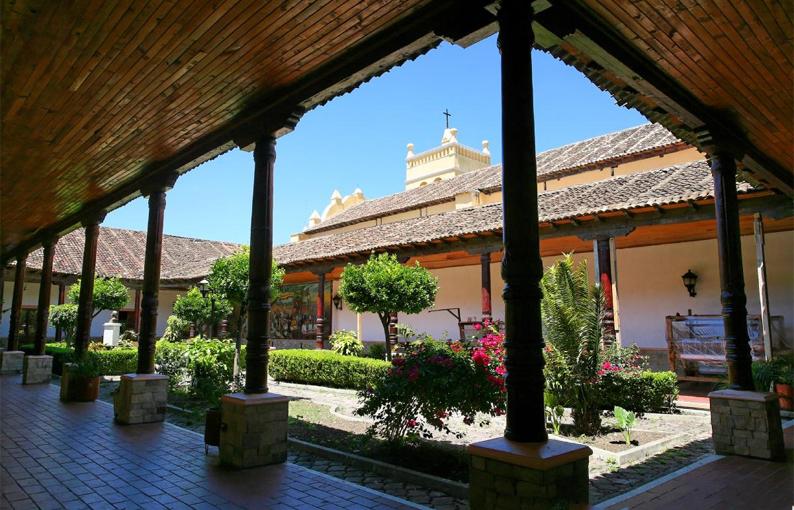

The civil architecture and urban physiognomy present elements dating from the 19th century. Proof of this are the buildings aligned to the street, composed of a central or lateral courtyard based on wooden columns with arches. These buildings employ a construction system based on adobe walls and a wooden structure that supports the tile roofs.

Templo de San José

On April 18, 1827, permission was granted to build a public chapel in honor of Saint Joseph the Patriarch at the expense and devotion of Casimiro Pérez, who donated the land and built the structure.

Templo de San José

On April 18, 1827, permission was granted to build a public chapel in honor of Saint Joseph the Patriarch at the expense and devotion of Casimiro Pérez, who donated the land and built the structure. The oratory cracked after the tremors caused by the eruption of the Santa María volcano in Guatemala, so it had to be rebuilt. On September 1, 1910, the first stone was laid.

Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán

This building was constructed by the Dominican friar Diego Tinoco in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. It is the oldest church in the city and has undergone several renovations. In 1914, it was occupied for four years by soldiers under the command of General Jiménez Méndez.

Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán

This building was constructed by the Dominican friar Diego Tinoco in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. It is the oldest church in the city and has undergone several renovations. In 1914, it was occupied for four years by soldiers under the command of General Jiménez Méndez. In 1918, the priest Belisario Trejo took charge again and provided the parish house with everything it needed.

San Caralampio

19th-century religious building

Portales

19th-century civil building

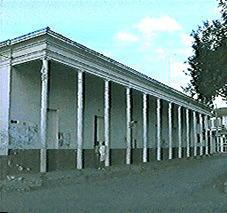

Casa Hogar Don Bosco

19th-century building

Templo de Santa Teresita del Niño Jesús

19th-century religious building

Museo Arqueológico de Comitán

Between 1960 and 1980, it was a primary school, then it became a municipal prison, and since 1991 it has been operating as a cultural center.

n>

Museo Arqueológico de Comitán

Between 1960 and 1980, it was a primary school, then it became a municipal prison, and since 1991 it has been operating as a cultural center.

n>

Propiedad privada

20th-century domestic architecture

n>

Casa habitación

20th-century domestic architecture

Centro Cultural Rosario Castellanos

In 1564, a Dominican convent was built; after the confiscation of church property, the convent became a barracks. The building was completely rebuilt in the 1930s, using stone for the walls and wood covered with tiles for the roof.

n>

Centro Cultural Rosario Castellanos

In 1564, a Dominican convent was built; after the confiscation of church property, the convent became a barracks. The building was completely rebuilt in the 1930s, using stone for the walls and wood covered with tiles for the roof. In 1946, it was occupied by public offices, and later became the Comitán Secondary and Preparatory School. In 1975, it became the first House of Culture in Chiapas, and since 1997, it has been the Rosario Castellanos Cultural Center, where art workshops and other activities are held.

Parque Central Benito Juárez