Orizaba

Historical Monuments Zone

Abstract

Watched over by the spectacular Pico de Orizaba, during the vice-regal period this city was a vital site of passage and stopover on the Veracruz-Mexico City reset, and home to an economically active population. Thanks to its climate and the many rivers running around and through it, it is known as the “city of happy waters” and “Pluviosilla”.

The city of Orizaba is located in the green and humid valley of Pico de Orizaba, in the center-east of the state of Veracruz. Its name derives from Nahuatl word Ahuializapan, which means “happy waters”. In the pre-Hispanic period it was a Totonaca settlement, conquered successively by Toltecs, Chichimecas and Mexicas, to which it paid tribute. In the colonial period, during the first half of the 16th century it remained a small village with a mostly indigenous population.

Soon, however, the valley acquired strategic importance for the Spaniards as a waypoint on the route between Veracruz and Mexico City. The route to the central altiplano through Orizaba was longer in terms of distance than the route via Xalapa, but shorter in time. Its large expanses of grazing lands, abundant water and a more temperate climate than that of the coast offered the mule caravans the chance to rest. This led to Orizaba’s transformation into a way station; later, it was surrounded by fields of corn, barley and sugar cane, and became a center for the sale and distribution of agricultural products.

The city was divided in two: to the south, the Spanish settlement, along the Royal Road; to the north, with a strip of empty land between them, the indigenous district of Ixhuatlán. At the end of the 16th century, a new indigenous district developed, known as Cocolapan, which widened the outline of the town. Over time it grew, with the timber houses in the Spanish district gradually replaced by lime and stone ones, even though they were still modest. The streets were laid out in an irregular manner, adapting to the passage of the wagons and following the predominant east-west orientation of the old Royal Road, from the barrio of San Juan de Dios towards the east.

In 1580, the prosperity of the Spanish businesses and the increase in the population were factors in the granting of Orizaba the title of cabecera de jurisdicción. From this moment on, the construction of stone buildings accelerated in the center of the town. Likewise, wealthy Spanish families came to settle and a first parish church was built, forming a nucleus for other buildings: the priest’s house, the council houses and a school.

In 1619 construction commenced on the Monastery of San Juan de Dios and later on the hospital beside the Orizaba river. In 1696 an earthquake levelled both buildings, forcing them to be rebuilt. It is highly likely that this tremor led to the authorities prohibiting the construction, anywhere in the city, of buildings over one story in height. Meanwhile, in the mid-17th century, the stone Church of Calvario was built in the indigenous district. In this period, Orizaba reached the size it would retain until the mid-19th century, even though there were several large spaces not built on.

In the 18th century tobacco crops brought about Orizaba’s golden age. Cultivation of this crop had gradually displaced sugar cane. When in 1764 the monarchy monopolized tobacco production, Orizaba was one of the few regions authorized to harvest it. This is the root of its prosperity, as one of the largest factories of cigars and cigarettes in all of New Spain was established here. The boom lasted until the outbreak of the War of Independence.

In the same period (the second half of the 18th century) the parish church and other chapels were built, together with the monasteries of Carmen, San Felipe Neri and San José de Gracia; the latter was based on plans by renowned architect Manuel Tolsá, in the early 19th century. Other buildings were constructed around the Church of Concordia, together with a bridge, and the roads were repaired. The De la Borda, Santa Anita, Escamela, Jalapilla and the La Angostura bridges were built, together with one in the village of Ingenio and another across the Metlac ravine. A road was laid from the city gate at La Angostura to the village of El Ingenio, greatly easing the transit through the city and across the valley.

The city saw a rapid increase in inhabitants, who occupied the areas within the town boundary as yet unbuilt on, thereby connecting up heretofore separate districts. By 1765 the construction of the council houses and the prison commenced on the main plaza, opposite the indigenous council house. In 1774 the town was awarded its coat of arms and the title of villa; in 1830, as part of independent Mexico, it acquired the title of city.

The city of Orizaba experienced some of the most significant episodes in Mexico’s history: one of the most important was in the 19th century during the French Intervention, when the city became a strategic point and the site of heroic battles. Subsequently, in the first two decades of the 20th century, Orizaba was the backdrop to key events: in 1906 it saw one of the first strikes in the country, in 1910 Francisco I. Madero passed through the city, in 1915 it was the headquarters of the House of the World Worker, and in 1919 the first strike was held under the aegis of Article 123 of the 1917 Constitution.

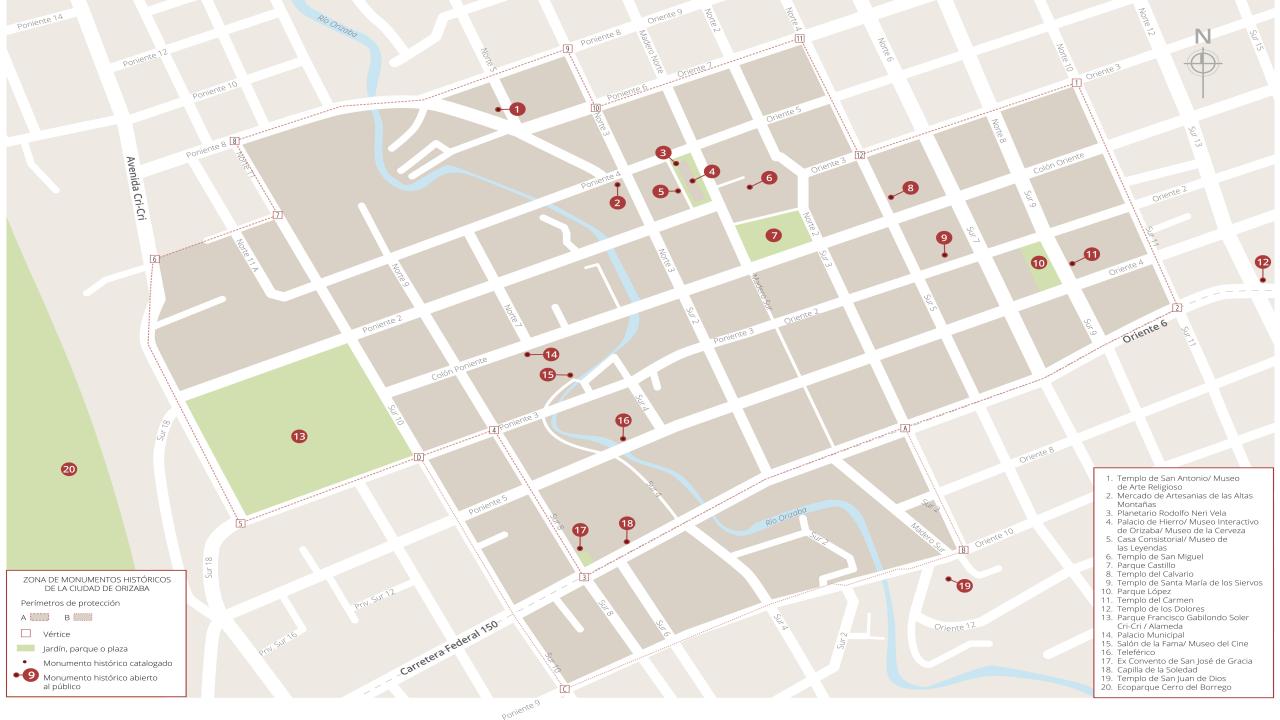

The Zone of Historical Monuments, declared on 25 January 1985, covers an area of 0.123 km2 and comprises 53 city blocks, which include religious buildings of historical significance. These include the church of San Miguel (parish church), the churches and former monasteries of San José de Gracia, El Carmen and San Juan de Dios, the chapel of Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, the churches of San Antonio, El Calvario, Santa María de los Siervosla Concordia and Santa Gertrudis; as well as the former oratory of San Felipe Neri.

This perimeter is also noted for its open spaces including the Plaza de Armas, the Parque Alberto López and the Alameda Prado Colón. Other emblematic buildings worthy of mention are the Ignacio de la Llave Theater, the Regional Institute of Fine Arts and the Town Hall.

Teatro Ignacio de la Llave

It was built at the initiative of Governor Ignacio de la Llave and inaugurated on January 1, 1875. The design by architect Joaquín Huerta follows the structure of the Italian theater, with a neoclassical style.

Teatro Ignacio de la Llave

It was built at the initiative of Governor Ignacio de la Llave and inaugurated on January 1, 1875. The design by architect Joaquín Huerta follows the structure of the Italian theater, with a neoclassical style. In 1973, it was struck by an earthquake that destroyed it, leaving only the facade; it wasn't until 1985 that the damaged structure was rebuilt using modern reinforced concrete systems.

Antigua Estación Orizaba

On January 1, 1873, the construction of the railway line was completed and put into service. This was one of the main stations of the former Mexican Railway, open to both freight and passenger trains. It underwent several phases of expansion and growth.

Antigua Estación Orizaba

On January 1, 1873, the construction of the railway line was completed and put into service. This was one of the main stations of the former Mexican Railway, open to both freight and passenger trains. It underwent several phases of expansion and growth.

Museo de Arte del Estado de Veracruz

Poliforum Mier y Pesado

Palacio de Hierro

Building designed by Gustave Eiffel in Art Nouveau style.

Catedral de Orizaba (San Miguel Arcángel)