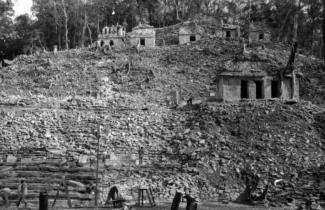

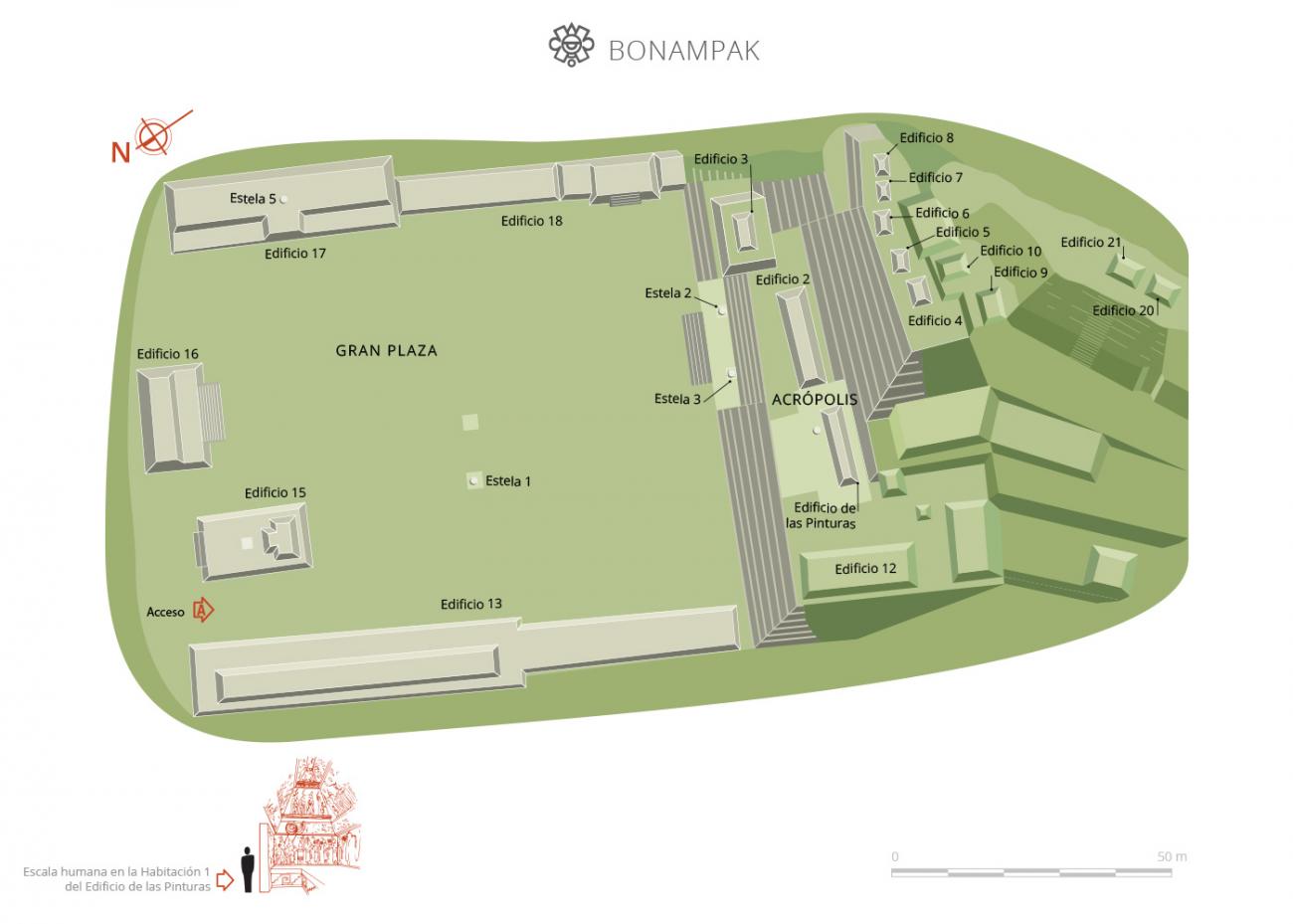

The Acropolis is built on a 46 m high hill, with three bodies formed by platforms, whose staggered bases give access to the buildings that were built in different stages.

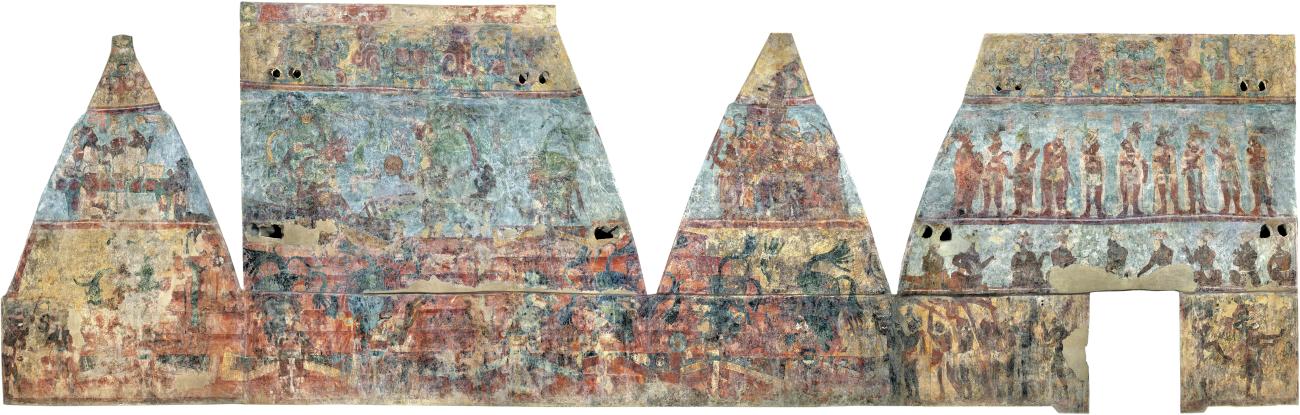

Building 1 or Temple of the Paintings: The Temple of the Paintings belongs to the last constructive sequence of the site and its murals are inscribed within the tradition of the Mayan painting of the Classic period (300-900 A.D.). Its base covers the remnants of a previous structure; the rooms that conform it are completely painted in its interior and show a chronological order in the thematic of its images.

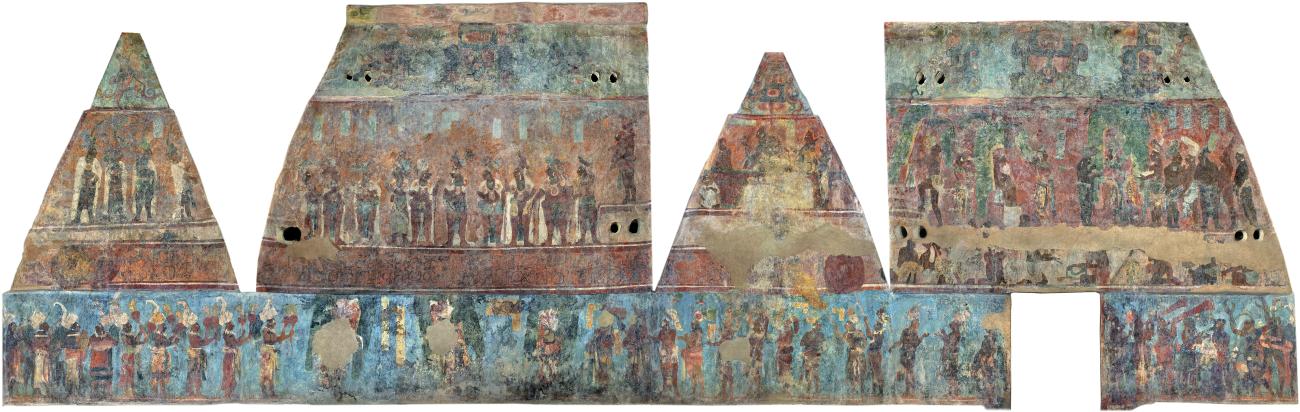

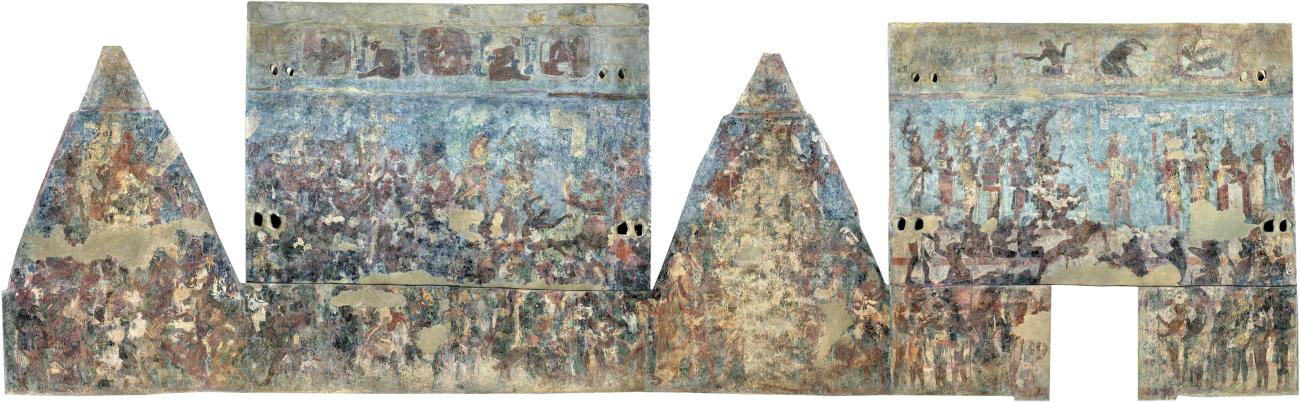

The construction divides the pictorial space into walls and vaults, in which the scenes are distributed in horizontal registers. In the upper register of the vaults and in the keyhole of the three rooms, figures related to the stars that preside over the historical and mythical events depicted in the rest of the pictorial space were painted.

Murals of Room 1, Temple of the Paintings: Its walls depict three scenes separated from each other by stripes alternating red and white colors. The first scene that covers the vaults is the presentation of the heir to the throne of Bonampak, distributed on the east, south and west sides; the second, on the north vault, is the clothing of a group of nobles; and the last, on the vertical walls, represents a group of musicians accompanying several characters, all distributed on the four sides.

Stainer Cicero, Leticia, 1998, La pintura mural prehispánica en México. Volume II, Maya area. Bonampak, Mexico, UNAM / IIE.

Murals of Room 2, Temple of the Paintings: The murals of this room relate two scenes: the most extensive is a battle, which occupies the east, south and west sides; the following, in the north, represents the subjugation and sacrifice of the captives in front of the victors. There are approximately 126 human figures, 41 glyphic clauses and 11 figures towards the closing of the vault.

Stainer Cicero, Leticia, 1998, La pintura mural prehispánica en México. Volume II, Maya area. Bonampak, Mexico, UNAM / IIE.

Murals of Room 3, Temple of the Paintings: Unlike the previous ones, the murals of this room show only one scene formed by different groups of characters: on the east, south and west sides it is a festivity in which sacrifices and dances are included, and two groups of spectators occupy the north vault. The number of human figures reaches 69, that of glyphic clauses 20, and 7 figures near the vault's closure.

Stainer Cicero, Leticia, 1998, La pintura mural prehispánica en México. Volume II, Maya area. Bonampak, Mexico, UNAM / IIE.

Building 3: It has a precinct with three entrances and the interior has stucco plaster covered in black, as well as several graffiti.

Buildings 4 - 8: They are small buildings with Mayan vault of more ritual than residential character. Number six is the oldest of the whole complex; it has a lintel carved with the image of the ruler Chaan Muan I, who ruled Bonampak around 600 AD.