Chapultepec Castle is a magnificent late-eighteenth century construction (1785-1787) designed and built as a stately home at the behest of the Viceroy of New Spain at the time, Bernardo de Gálvez. Over the years, however, the building has been adapted several times for different uses. It was the headquarters of Mexico’s military academy, the site of battles fought during the US invasion, residence of Emperor Maximilian and Empress Carlota, and of a number of Mexican presidents. President Lázaro Cárdenas eventually issued a presidential decree in 1939 for the Castle to be used as a museum housing the collections and personal effects of Mexico’s leading historical figures. The building, standing at the highest point of Chapultepec Park, opened its doors as a museum in September 1944.

The National Museum of History—undoubtedly one of the most important exhibition spaces in Mexico—offers visitors a comprehensive view of national history, from the Conquest and the founding of New Spain until the dawn of the twentieth century. On display are more than 65,000 objects including paintings, sculptures, furniture, clothing, coins, musical instruments, silver and ceramic utensils, flags, carriages, and documents.

In the former military academy the galleries’ exhibits date from the time of the Conquest until the 1910 Revolution. Visitors to this part of the museum can also admire mural paintings created by leading artists between 1933 and 1970, notably Jorge González Camarena’s “La fusión de dos culturas” (“Fusion of Two Cultures”) and “La Constitución de 1917” (“1917 Constitution”); Juan O’Gorman’s “El retablo de la Independencia” (“Independence Altarpiece”), “El feudalismo porfirista” (“Porfirian Feudalism”) and “Sufragio Efectivo, no Reelección” (“Effective Suffrage, No Reelection”); José Clemente Orozco’s "La Reforma y la caída del Imperio" (“The Reform and the Fall of the Empire”), and Siqueiros’s “Del Porfirismo a la Revolución” (“From the Dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz to the Revolution”).

The ground-floor rooms in the building known as the Alcázar (“Fortress”) are decorated with furniture, domestic items, jewelry, paintings and various objects related mainly to the imperial era of Maximilian and Carlota, while the top floor contains the furniture, paintings and other belongings of President Porfirio Díaz and his wife Carmen Romero Rubio.

Chapultepec Hill and the Chapultepec Castle’s National Museum of History have their own history. In pre-Hispanic times, Moctezuma had his pools and baths here, as well as a shrine and living quarters; it is also known that Moctezuma I ordered the construction of the aqueduct to carry water from Chapultepec to Mexico-Tenochtitlan, and that Nezahualcóyotl, Lord of Texcoco, was responsible for the actual building work.

Construction on this hilltop took place between 1785 and 1787; the residence was commissioned by Viceroy Bernardo de Gálvez, who died before seeing it completed. Due to the building’s exorbitant cost, the Spanish crown tried to sell it but there were no buyers and it fell into disuse.

The Mexico City government acquired the property in 1806, but at the outbreak of the War of Independence it did not make any further use of it. It was not until 1833 that a decree was issued for it to be converted into a military academy and, after a period of alterations, it began to operate as such in 1844. On September 12 and 13, 1847, it resisted bombardment from the US army, which nevertheless caused it serious damage. After its reconstruction, the military academy reopened and Miguel Miramón, a former pupil and survivor of the Battle of Chapultepec in 1847, ordered the construction of some rooms on the second floor of the Alcázar. However, its current appearance dates from the time when Maximilian and Carlota decided to make it their imperial residence, and their team of Austrian, French, Belgian, and Mexican architects transformed it. At the end of the Second Mexican Empire, the building was abandoned once again.

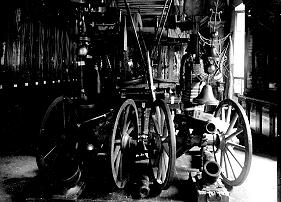

From 1878 to 1883 it briefly became an astronomical, meteorological and magnetic observatory, until the military academy returned, and the Castle itself was converted into a presidential residence, providing a home successively for Porfirio Díaz, Francisco I. Madero, Venustiano Carranza, Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, Emilio Portes Gil, Pascual Ortiz Rubio and Abelardo Rodríguez. On February 3, 1939, it was declared the National Museum of History.