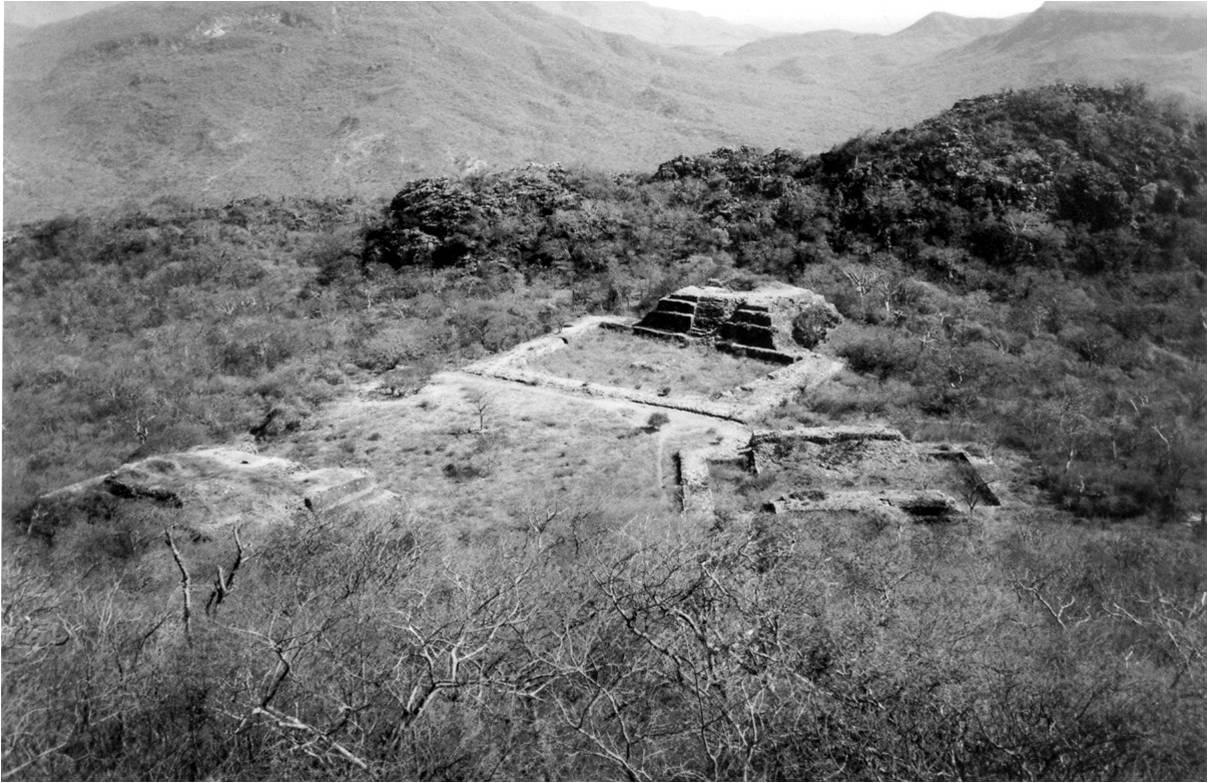

Guiengola is situated on a hill of the same name. The course of the Tehuantepec River runs to the west of this limestone hill with many caves, making its way to the Gulf of Tehuantepec.

According to seventeenth-century sources, the Zapotecs of this settlement were allied with the Mixtecs to defend the isthmus territory against the advance of the imperialist Mexica in their push to the Soconusco region of Chiapas. The isthmus was controlled by the Zapotecs from the Central Valleys, who made use of its varied natural resources. The Mexica were defeated and had to agree a marriage alliance.

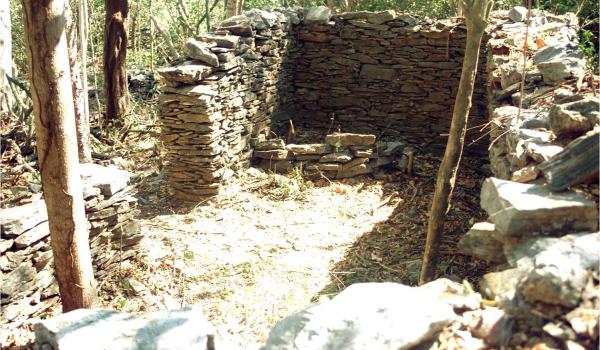

It is said that this site was built purposely as a fortress and its location certainly made it unassailable. It was an impregnable fortress with well-planned construction and the topography was carefully exploited. In short, it was a fortified place with seven-foot-wide defensive walls with a height of 10 to 16 feet, depending on the position on the hill. River stones were placed at regular intervals along the enormous defensive wall surrounding a part of the hill. Examples of military infrastructure include probable stores for foodstuff, the remains of a few controlled tight access points as well as surveillance posts.

This fortified civic-ceremonial center of the Postclassic period was described by Fray Francisco de Burgoa in his geographical work. Among the first to visit the site were Guillaume Dupaix, Charles Brasseur de Bourbourg, Teobert Maler and Eduard Seler.

The formal archeological investigation of the site began in the 1950s. In 1955 James Forster obtained collections of ceramics and figurines from Guiengola and from the nearby sites of Juchitán, Tlacotepec and Mixtequilla. He made a contribution to understanding the styles of these artifacts and finds from other regions of Mesoamerica. The archeologist David Peterson published the first piece in a series of works on the site in 1972. He wrote his most important work with Thomas MacDougall in 1974, the result of several mapping exercises, which were the basis for the plans drawn of the principal structures. In this work Paterson records relatively unknown structures and mentions building techniques and the looting they had suffered, among other matters.

Martín Cendrero published his bachelor’s degree thesis on the site, the only one to date (ENAH, 1986). The author did no excavation, but he did record the site’s in situ materials and explored the whole mountain. A decade later, in 1997, Roberto Zárate made a similar survey for a study focused on the rock art, reporting that many of the overhangs contain paintings of this kind, but he also noted the damage to some of these works.