This Mayan port city from the Classical period had a lengthy occupation (200 BC - 900 AD). The Nahua traders who found it after it had been abandoned named it Comalcalco, which means “in the house of the griddles.” To date, the only inscription found in the site is written on a brick in the Mayan language ch’olano and says “Joy’Chan,” a word which can be translated as “rolling sky.” The earliest historical record of the site is from August 10 of the year 561, whilst the latest date found is March 7, 814. This is when it began to decline and disappear into the rainforest, which would conceal it for more than a thousand years.

The city was founded on the bank of the Mezcalapa river on the Tabasco alluvial plateau, within a large lagoon system near the sea. This allowed the Joy’Chan Mayans to keep control of the clay deposits from which they made multiple objects, such as bricks, drains, crockery, urns and statuettes, among others. Thanks to fishing and gathering of species from the lowland rainforest floodplains (mangrove swamps), and an intensive agriculture based on the farming of corn, beans and cacao, it became the most important tradng port not only of the region, but also for distant areas. The traders who traversed this valuable river route used to move between the Cuchumatanes mountain range in Guatemala and the present-day states of Chiapas and Tabasco, down to the river mouth in the Gulf of Mexico.

The production of handmade goods in Comalcalco allowed its local inhabitants and traders to obtain obsidian, flint, jade and basalt, among many other raw materials, for the production of tools, spoons, axes, grinding stones and mortars, to mention but a few. A key product made locally were figurines of animals and individuals moulded from clay. Particularly special among these is a representation of a female who holds a fan in her right hand and wears a decorated blouse. She has been called the Lady of Comalcalco and is considered to be the ideal model of a woman from the region.

The farming of the cocoa bean drove the development of the economy. During its time of prosperity, the city established ties with important trading ports on the coastal border of the Gulf of Mexico and sites along the banks of the Mezcalapa river, with which it traded high quality ceramics and figurines, which have now been found in sites such as Jaina, Campeche and Xcambó in Yucatán. It also maintained commercial and political relationships with cities like Jonuta, Palenque and Tortuguero.

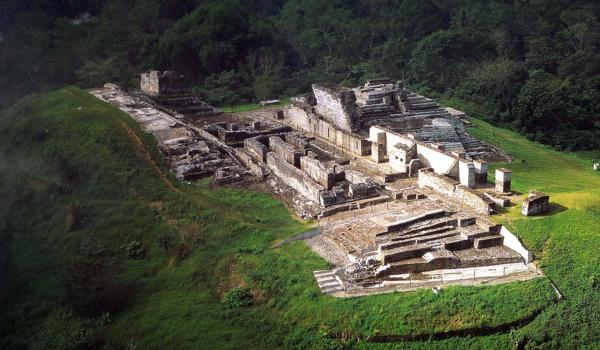

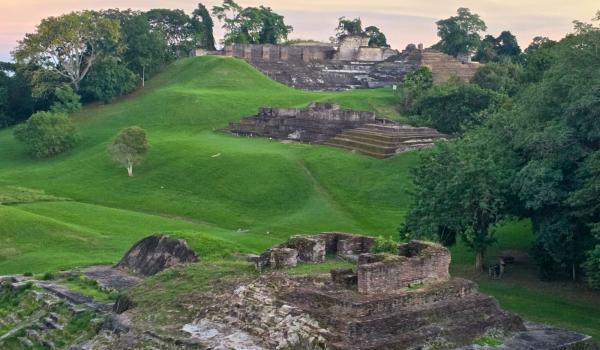

Its spectacular architecture is comprised of earth plinths covered in stucco. On top of these were temples with arched roofs, built with thousands of bricks. They were adorned with attractive cresting and had plaster sculptures attached to them, showing figures from the royal family. These characters appeared in scenes which combine gods, animals and aquatic plants associated with the culture’s world view, which were painted with lavish polychrome, endowing them with great vitality and realism.

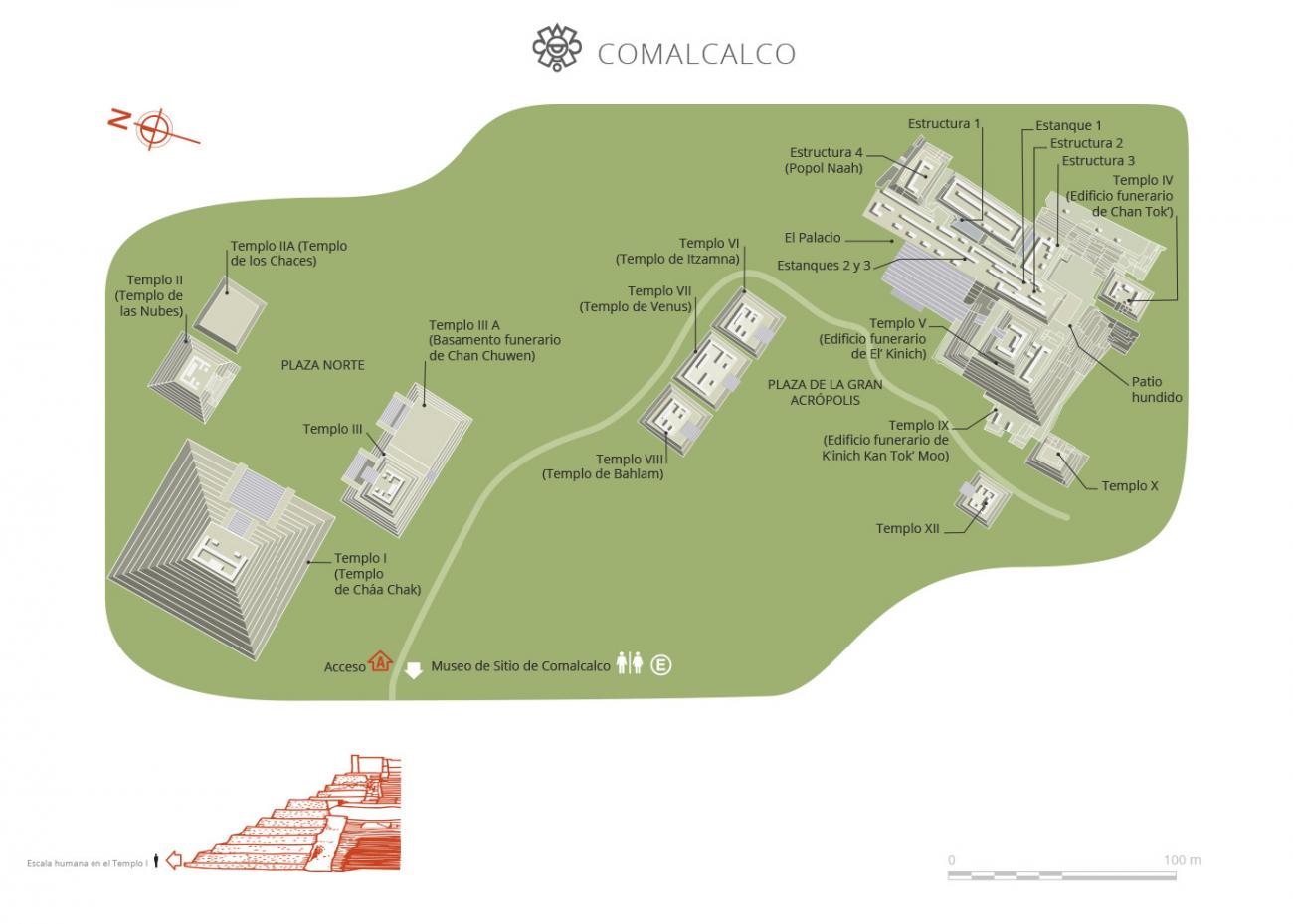

In Comalcalco, the main architectural sites are the Northern Plaza, the Great Acropolis, the Eastern Acropolis and the Western Group. These were built on domes of earth, which made it easy to orient them towards the cardinal points on an axis which runs in an orderly sequence from east to west. The scale of the Northern Plaza suggests that it served as the tianquiztli (market). It is found near to the river channel and the piers where people and goods disembarked, but at the same time far enough away to avoid floods in the rainy season. As for the Great Acropolis, it is the most outstanding architectural complex of the site. It is in the shape of a horseshoe, is 125 feet high and has an area of 11.8 acres.

Comalcalco was discovered in 1880 by Désiré Charnay. In 1925, it was described and photographed by Frans Blom and Oliver La Farge, and Gordon Eckohlm studied it in 1956-1957. In 1960, Román Piña Chan began the excavation of six buildings in the Great Acropolis, and in 1966 George F. Andrews carried out a topographic and architectural survey of the central area of the site. Between 1972 and 1981 Ponciano Salazar added seven buildings to the areas open to the public, and from 1993 to 2016 Ricardo Armijo excavated, restored and investigated 13 more buildings in the Great Acropolis and the Northern Plaza.

The historical record of the site spans 300 years, and confirms the existence of an emblematic glyph which reveals the settlement’s importance. It also mentions a great war which resulted in the capture and beheading of Kuhul Ajau Ox Balam on December 23 of the year 649. From this time on, the city remained subject to the kingdom of B’aakal (Palenque) and adopted its emblematic glyph from then on.