An overview of the rich history of Acapulco in the emblematic San Diego Fortress. It is the most important historical monument in the port of Acapulco, unique in Mexico due to the classic “star” design of Marquis de Vauban, military architect to Louis XIV, and is typical of Spanish forts after the enthronement of the Bourbons following the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1715). With its singular geometric design in the shape of a pentagon or five-pointed star, the building fulfilled the Spanish crown’s policy to maintain a defensive structure for its possessions on the Pacific coast. The fort was intended to protect the galleons which landed in Acapulco at the end of their “return trip” journey from Manila, carrying valuable goods from China (silk, porcelain, brocade) and other places in the East. This trade lasted for 250 years.

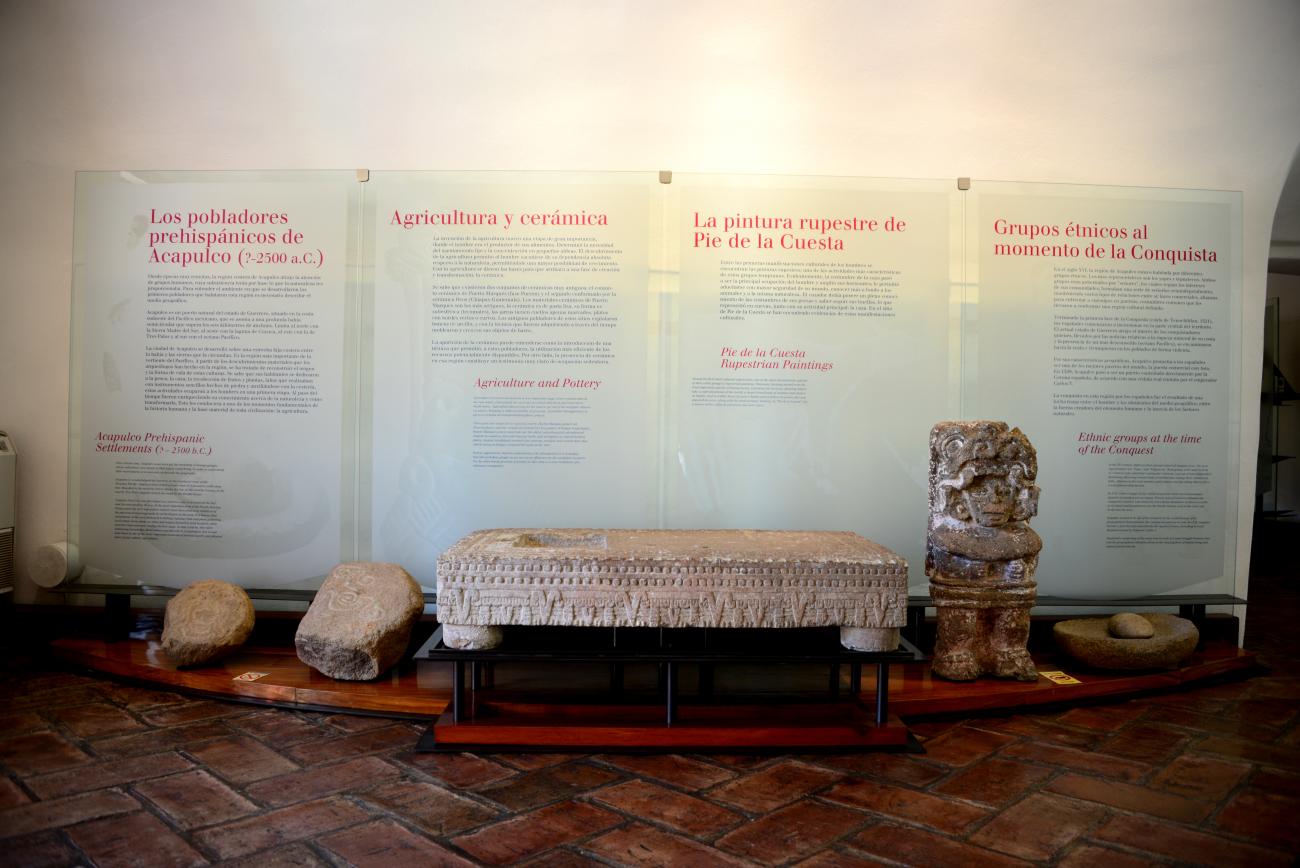

Since 1986, thanks to joint work between the INAH, the National and State “Adopt a Work of Art” Boards, and the Association of Friends of the Fuerte de San Diego, this huge building has housed the Acapulco History Museum. With 14 permanent exhibition galleries and one temporary exhibition space, it provides the people of Guerrero and of Mexico in general with an overview of their history. It offers visitors a summary of the evolution of the port: the first settlers, the conquest of the Southern Seas (the Pacific Ocean), trade with the East, pirates, the spread of the Christian faith and the War of Independence. The independence leader José María Morelos y Pavón, following the struggle to capture the site (he lay siege to the fort for two years and seven months, between 1811 and 1813), authorized a banquet in the Fort of San Diego, and in the kitchen and dining hall he raised the toast: “Long live Spain, yes, but a sister Spain and not one that dominates America!”

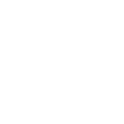

The pieces on show are both archeological (from Guerrero’s Mezcala culture) and historical in character. They belong to the museum’s own collection and are enriched with objects loaned from other institutions, such as the National History Museum and the National Museum of the Viceroyalty, as well as with personal items, such as the valuable collection of antiques dealer Rodrigo Rivero Lake.

One noteworthy object in the museum is an opulent carriage known as the “royal carriage,” as well as some figureheads from the eighteenth century, a large Chinese porcelain jar also from the eighteenth century, as well as silk and embroidery, an old silk kimono and Chinese coins from ancient dynasties, to mention but a few. Among the most important and iconic objects exhibited in the museum is the galleon San Pedro de Cardeña. It is a European model from the eighteenth century, made of wood, metal, fabric and tin thread, both assembled and carved, colored brown, black, ochre and gold and measures 90 inches in height, 100 inches in length and 109 inches in width. In the absence of technical drawings, miniatures like this were built to construct the galleons.

Collections of Chinese porcelain from different periods also play an important role. These are mainly from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and some is from the Qing dynasty. There are also plates, platters and china cups from the Indies Companies, a generic name by which all original porcelain from the Far East is recognized, manufactured in China since ancient times. Huge quantities of this very fine crockery arrived in Mexico thanks to the Manila Galleon.

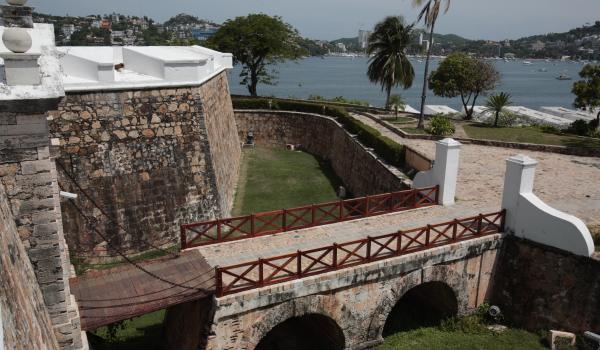

The Fuerte de San Diego is the most important maritime fortresses on Mexico’s Pacific coast. It is located in a reef, in the current district of Petaquillas. Its construction in 1616 was overseen by the engineer Adrián Boot, of Dutch origin (from then Spanish Flanders). He gave it the name of San Diego in honor of the patron saint of the 13th Viceroy of New Spain (1612-1621), Diego Fernández de Córdoba, Marquis of Guadalcázar. The bastions around the wall were given the names “King,” “Prince,” “Duke,” “Marquis,” and “Guadalcázar.” In 1776 to 1778, following a strong earthquake which seriously damaged the port, it was renovated by the engineer Miguel Constanzó (based on the design of engineer Ramón Panón), who rebuilt the fortress with five bastions and surrounded by a moat. The reconstruction work was finished in 1783. It had room for two thousand soldiers with provisions and drinking water all year round, and was supplied with 63 long distance cannons. Later, it became a monastery, hospital and prison. In 1933, President Abelardo Rodríguez declared it to be a national monument, in 1959 it hosted the Worldwide Cinema Review and from April 24, 1986, it has been the headquarters of the Acapulco History Museum.