Central Highlands

Mexico’s central region comprises four zones with interlinked cultural traditions: the Valley of Morelos to the south, the Puebla-Tlaxcala Valley in the east, the Mexico Basin in the center and the Valley of Toluca in the west. The Valley of Morelos is the only one with a hot climate. On the other hand the three zones surrounded by high mountains to the north of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt are over 6,500 feet above sea level. These are vast areas of fertile soils, which in pre-Hispanic times had important river and lake systems.

The oldest signs of settlement are in places like Tlapacoya, Texcal and in several caves on the Tehuacan site, where evidence of the first nomadic groups was found, as well as signs of their gradual transformation into sedentary and agricultural societies.

Settlements such as Tlatilco and Chalcatzingo sprung up in the Middle Preclassic (1200-400 BC), showing significant Olmec influence. The settlement of Cuicuilco grew in the Late Preclassic (400 BC-200 AD) and was the site of the region’s first monumental public structures, while Teotihuacan started its rise between 300 and 100 BC. A series of eruptions of the Xitle volcano caused Cuicuilco to be abandoned around the beginning of the Common Era, as well as a mass population movement involving three quarters of the people of the Basin who went to the Valley of Teotihuacan.

The Classic horizon from 200 to 900 AD witnessed the first large scale urban phenomenon, with advanced urban planning and a high population density, living in residential complexes. Slope-panel was a typical feature of its architectural technique, as seen in the temples and the complexes lining the great central avenues. Teotihuacan consolidated its power and established vast exchange networks linking up distant regions, for the first time forming an integrated Mesoamerican culture. The aspects of Teotihuacan’s culture which spread elsewhere were: slope-panel architecture, the 260 day and 365 day calendars for ritual and farming purposes respectively, as well as the worship of the Plumed Serpent.

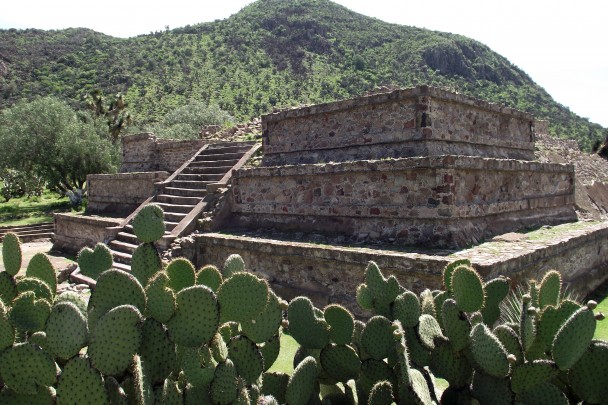

In the Epiclassic (650-900) Teotihuacan commenced a process of deterioration which culminated in its collapse, giving way to other Central Highland cities such as Cacaxtla, Xochicalco, Tula and Cholula, which acquired importance as political capitals. These centers created their own artistic styles and some of them combined elements of several cultures harmoniously, as can be appreciated from the Cacaxtla murals, the Xochicalco reliefs and the architectural features of cities such as Cantona, San Miguel Ixtapan and Teotenago.

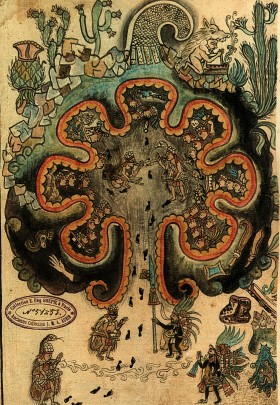

Tula dominated a large swathe of central Mexico in the Early Postclassic (900-1200), basing its power on the god Quetzalcoatl. After its fall other sites came to dominate smaller territories, notably Huamango, Calixtlahuaca, Texcoco, Cholula, Huexotzinco and Azcapotzalco. The Nahua political centers sought to rule other regions linked by their Toltec heritage and their overlord, Quetzalcoatl. This was how Azcapotzalco developed. Originally a Tepanec city, it ruled over the Highland towns when the Mexica first arrived in the area.

The Mexica and the people of Texcoco defeated Azcapotzalco and other Tepanec territories in 1430, forming a politico-military alliance with Texcoco and Tlacopan (Tacuba). It was known as the Triple Alliance. The governors of the three cities aided each other politically, economically and militarily, and the alliance made possible a series of conquests which led to the subjugation of more than 400 towns and fiefdoms in Mesoamerica. Despite the Triple Alliance’s great influence there were places which managed to resist the might of the Mexica and stay free of its political influence. These included Metztitlan, Tlaxcala, Cholula and Yopitzinco.