El Tigre

(The tiger) Gets its name from the ejido (communal farm land) where it is located.

Capital of the province of Acalán, also known as Itzamkanac, El Tigre is situated on the banks of the river Candelaria and was renowned for its trading activity. Notable is the ceremonial center with the large stucco masks. It is believed that Hernán Cortés executed Cuauhtémoc here.

About the site

The archeological site was named after the neighboring ejido, but in ancient times it was called Itzamkanac, meaning the place of the lizard or serpent, possibly in reference to the god Itzamna. El Tigre was the Acalan capital. Its status was reflected in the monumental size of its buildings and the extent of the urban footprint. It is speculated that this was the site of the execution of Cuauhtemoc by Hernan Cortes.

The region’s inhabitants were Chontal Maya, or Putun as Eric Thompson called them. They were traders, warriors and priests who imposed the worship of Kukulcan. Their territory stretched from Champotón to the Grijalva-Usumacinta basin, in other words from the Gulf coast inland, and they settled the northeast Mayan lowland river banks and lake margins in the present day states of Campeche, Tabasco and Chiapas.

El Tigre covers a series of low ridges next to the river Candelaria and has a long history of settlement stretching from the Middle Preclassic (600–300 BC) to around 1557, after the conquest. Until a few years ago, it was thought that Chontal settlement of this area took place in the Late Postclassic, but thanks to the ongoing excavations, we know that it reached its apogee during the Terminal Classic, since this was when the majority of the building took place. There is also evidence for significant settlement during the Middle and particularly in the Late Preclassic when coastal activity was very significant. The area was still populated when the Spanish arrived.

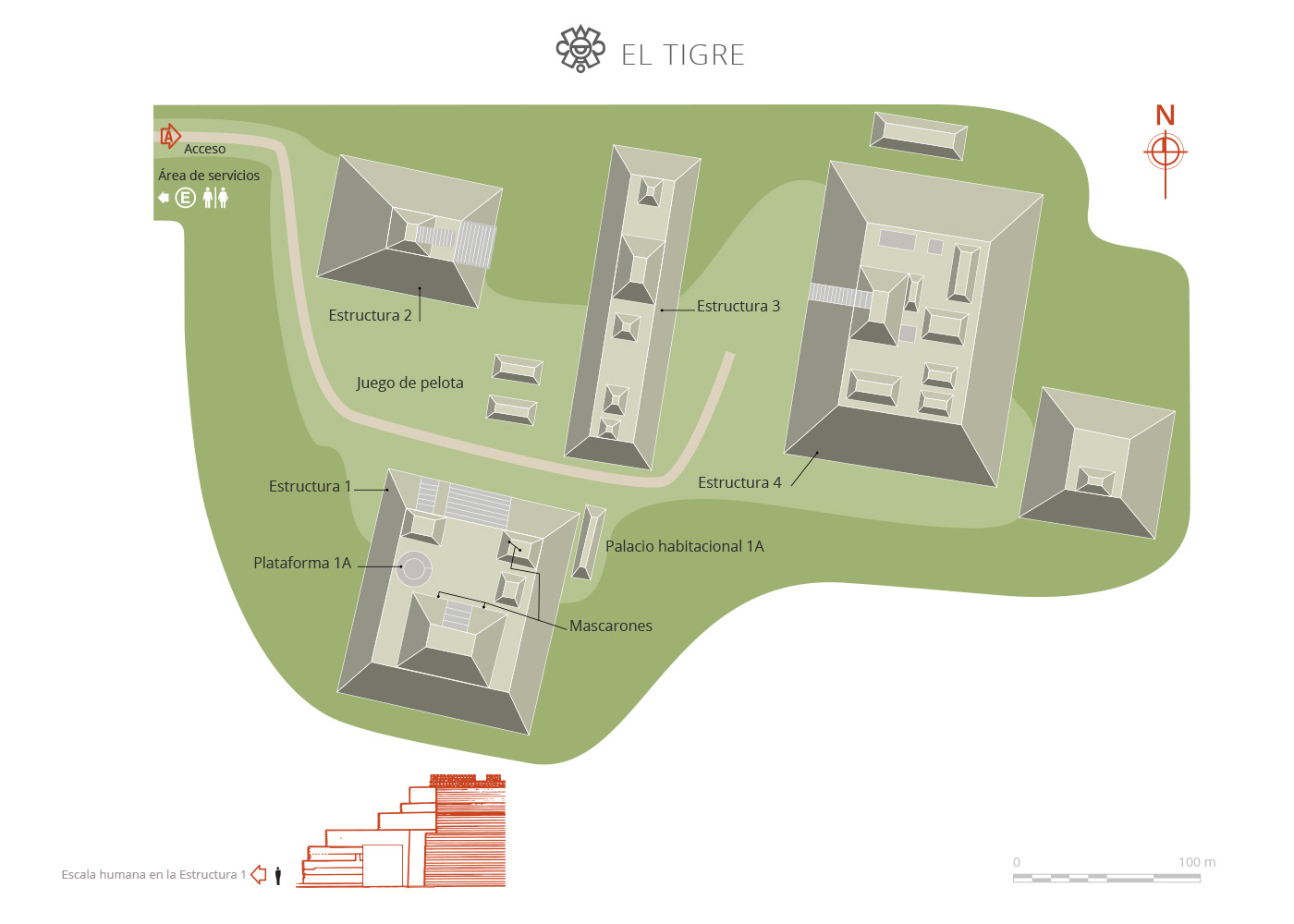

The archeological site is made up of six architectural groups, and the core area includes Peten-style buildings in the underlying structures. There are also elements of Rio Bec architecture from the later period. El Tigre’s main ceremonial center was distributed between two large plazas. The first and most important is the physical center of Structures 1, 2 and 3, which is classed as an E-group, although it is sometimes difficult to identify structures like these because of the substantial changes made in the Late Classic, undoubtedly because of social and political change in the region.

The internal arrangement of El Tigre has remained intact from at least the Middle to Late Preclassic. This is the site of Structures 2 and 3 which have Peten-style features, widespread in the Mayan southern lowlands. It is also possibly the oldest architectural pattern identified in them to date. The buildings were first interpreted as potential observatories and astronomical markers of the equinoxes and solstices, a purpose that was undoubtedly lost in the Classic period. The current thinking is that they were very closely tied to the identity of the elites and to divination using lines, circles and points marked out in the ground. The astronomical interpretation cannot be dismissed, however, and there would in any case have been a close relationship with the elites, and possibly with the agricultural calendar.

The stelae appear to be an important additional component since they are often located on the axes of these structures. At El Tigre a stela was found in alignment with the E-group axis. Although very fragmented and out of place, we do know where it used to be and we may assume it had been situated on this axis.

Stucco facade masks may also be considered elements of significance, since they are frequently found in the few sites that have been excavated. At El Tigre, for example, anthropomorphic facade masks were found at the sides of the stairways of Structure 2 facing towards the east, which may be identified with the ancestors, or with the establishment of lineages during this period. Two anthropomorphic facade masks facing the east were also found in Structure 4, but since the excavation was limited, it was not possible to determine whether there was a stairway between the two. There are also three ballcourts.

The first excavations at El Tigre were carried out in 1943 by Edward Wyllys Andrews IV who worked in various parts of the Mayan region. He highlighted the absence of information on southern Campeche, particularly on the municipalities of El Carmen and Candelaria. Even at the time Andrews emphasized the importance of El Tigre, although he had not visited all the sites to the south of the river Candelaria. The same year Alberto Ruz Lhuillier visited the coast of Campeche, but without going inland. It was not until 1959 that Román Piña Chan and Pavón Abreu published a paper on the ruins of El Tigre, proposing the hypothesis that the site is Itzamkanac, the capital of the province of Acalan, the place where Cortes killed Cuauhtémoc on the ill-fated journey to Las Hibueras.

INAH’s 1960 publication of volume two of the Atlas of Mexican Archeology included El Tigre as one of the sites mentioned in Campeche. The work of Alfred H. Siemens and Dennis E. Puleston on the canals of the river Candelaria, including the first preliminary map of the El Tigre, was published in 1972. An archeological survey of the river Candelaria basin was carried out in 1983 and the region was divided into seven sections, covering 33 archeological sites. El Tigre was one of those described.

The El Tigre Archeological Project commenced in 1984 under the direction of Dr. Román Piña Chan. Some residential areas were excavated as well as two of the site’s principal structures, which were numbered 1 and 2. Unfortunately the report and the project itself were never concluded. A year later Sofía Pincemín undertook a survey of the Candelaria basin, and more recently she has carried out intensive work in three different parts of the same basin. Nevertheless, despite these various archeological projects the region’s settlement pattern remains largely unknown. Nor do we understand the chronology of the sites, their architecture or their ceramic typology.

In 1996 the INAH Archeological Council approved the El Tigre, Itzamkanac, Provincial Capital of Acalan Archeological Project. The work includes recording the main sites in the province of Acalan, topographical surveys of the structures excavated in 1984, determining the boundaries of the El Tigre site and detailed surveying of the two residential structures, as well as an overall survey of the former province of Acalan, where 148 sites have been found.

The region’s inhabitants were Chontal Maya, or Putun as Eric Thompson called them. They were traders, warriors and priests who imposed the worship of Kukulcan. Their territory stretched from Champotón to the Grijalva-Usumacinta basin, in other words from the Gulf coast inland, and they settled the northeast Mayan lowland river banks and lake margins in the present day states of Campeche, Tabasco and Chiapas.

El Tigre covers a series of low ridges next to the river Candelaria and has a long history of settlement stretching from the Middle Preclassic (600–300 BC) to around 1557, after the conquest. Until a few years ago, it was thought that Chontal settlement of this area took place in the Late Postclassic, but thanks to the ongoing excavations, we know that it reached its apogee during the Terminal Classic, since this was when the majority of the building took place. There is also evidence for significant settlement during the Middle and particularly in the Late Preclassic when coastal activity was very significant. The area was still populated when the Spanish arrived.

The archeological site is made up of six architectural groups, and the core area includes Peten-style buildings in the underlying structures. There are also elements of Rio Bec architecture from the later period. El Tigre’s main ceremonial center was distributed between two large plazas. The first and most important is the physical center of Structures 1, 2 and 3, which is classed as an E-group, although it is sometimes difficult to identify structures like these because of the substantial changes made in the Late Classic, undoubtedly because of social and political change in the region.

The internal arrangement of El Tigre has remained intact from at least the Middle to Late Preclassic. This is the site of Structures 2 and 3 which have Peten-style features, widespread in the Mayan southern lowlands. It is also possibly the oldest architectural pattern identified in them to date. The buildings were first interpreted as potential observatories and astronomical markers of the equinoxes and solstices, a purpose that was undoubtedly lost in the Classic period. The current thinking is that they were very closely tied to the identity of the elites and to divination using lines, circles and points marked out in the ground. The astronomical interpretation cannot be dismissed, however, and there would in any case have been a close relationship with the elites, and possibly with the agricultural calendar.

The stelae appear to be an important additional component since they are often located on the axes of these structures. At El Tigre a stela was found in alignment with the E-group axis. Although very fragmented and out of place, we do know where it used to be and we may assume it had been situated on this axis.

Stucco facade masks may also be considered elements of significance, since they are frequently found in the few sites that have been excavated. At El Tigre, for example, anthropomorphic facade masks were found at the sides of the stairways of Structure 2 facing towards the east, which may be identified with the ancestors, or with the establishment of lineages during this period. Two anthropomorphic facade masks facing the east were also found in Structure 4, but since the excavation was limited, it was not possible to determine whether there was a stairway between the two. There are also three ballcourts.

The first excavations at El Tigre were carried out in 1943 by Edward Wyllys Andrews IV who worked in various parts of the Mayan region. He highlighted the absence of information on southern Campeche, particularly on the municipalities of El Carmen and Candelaria. Even at the time Andrews emphasized the importance of El Tigre, although he had not visited all the sites to the south of the river Candelaria. The same year Alberto Ruz Lhuillier visited the coast of Campeche, but without going inland. It was not until 1959 that Román Piña Chan and Pavón Abreu published a paper on the ruins of El Tigre, proposing the hypothesis that the site is Itzamkanac, the capital of the province of Acalan, the place where Cortes killed Cuauhtémoc on the ill-fated journey to Las Hibueras.

INAH’s 1960 publication of volume two of the Atlas of Mexican Archeology included El Tigre as one of the sites mentioned in Campeche. The work of Alfred H. Siemens and Dennis E. Puleston on the canals of the river Candelaria, including the first preliminary map of the El Tigre, was published in 1972. An archeological survey of the river Candelaria basin was carried out in 1983 and the region was divided into seven sections, covering 33 archeological sites. El Tigre was one of those described.

The El Tigre Archeological Project commenced in 1984 under the direction of Dr. Román Piña Chan. Some residential areas were excavated as well as two of the site’s principal structures, which were numbered 1 and 2. Unfortunately the report and the project itself were never concluded. A year later Sofía Pincemín undertook a survey of the Candelaria basin, and more recently she has carried out intensive work in three different parts of the same basin. Nevertheless, despite these various archeological projects the region’s settlement pattern remains largely unknown. Nor do we understand the chronology of the sites, their architecture or their ceramic typology.

In 1996 the INAH Archeological Council approved the El Tigre, Itzamkanac, Provincial Capital of Acalan Archeological Project. The work includes recording the main sites in the province of Acalan, topographical surveys of the structures excavated in 1984, determining the boundaries of the El Tigre site and detailed surveying of the two residential structures, as well as an overall survey of the former province of Acalan, where 148 sites have been found.

Map

Did you know...

- In the pre-Hispanic period this anciente Mayan city was a major trading port.

- The Chontales were the leading Mayan traders. Thompson called them the Phoenecians of America.

- The site contains a large number of facade masks, not all of them excavated. To date eleven have been discovered, some anthropomorphic and others zoomorphic, all from the Late Preclassic.

An expert point of view

Ernesto Vargas Pacheco

Practical information

Monday to Sunday from 8:00 to 17:00 hrs. Last entry 16:45 hrs.

$75.00 pesos

Se localiza al suroeste del estado de Campeche, a 40 km del poblado de Calendaria.

Desde la capital campechana la distancia a El Tigre es de 250 km.

From the city of Campeche take the Escárcega-Villahermosa highway. Upon reaching the town of Nuevo Coahuila continue on the turn off towards Monclova and, at km 13.5, you will find a road that leads to the site. The site can also be reached by boat, starting from the town of Candelaria, situated on the river of the same name.

Services

-

+52 (981) 816 9111 ext. 138016

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

FACEBOOK

-

TWITTER

Directory

Encargada de Operación de Zonas Arqueológicas del Centro INAH Campeche

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (981) 816 9136, ext. 138016