The earliest signs of human occupation at this site have been dated to 400 BC. Shortly before the beginning of the Common Era, a small community developed and created a centralized government. Over time, the inhabitants built a complex and efficient system for the collection and storage of rainwater, as well as a drainage network. They also concentrated production and the workforce, erected large buildings and dominated the surrounding villages. Edzná became a powerful regional capital in the west of the Yucatán peninsula between 400 and 1000 AD. The ancient city of Edzná covered an average area of almost 10 square miles and estimates suggest that at its peak—when it formed an alliance with Calakmul and Piedras Negras—its total population numbered some 25,000. Over the next four centuries it lost its political and financial power until it was eventually abandoned in around 1450 AD.

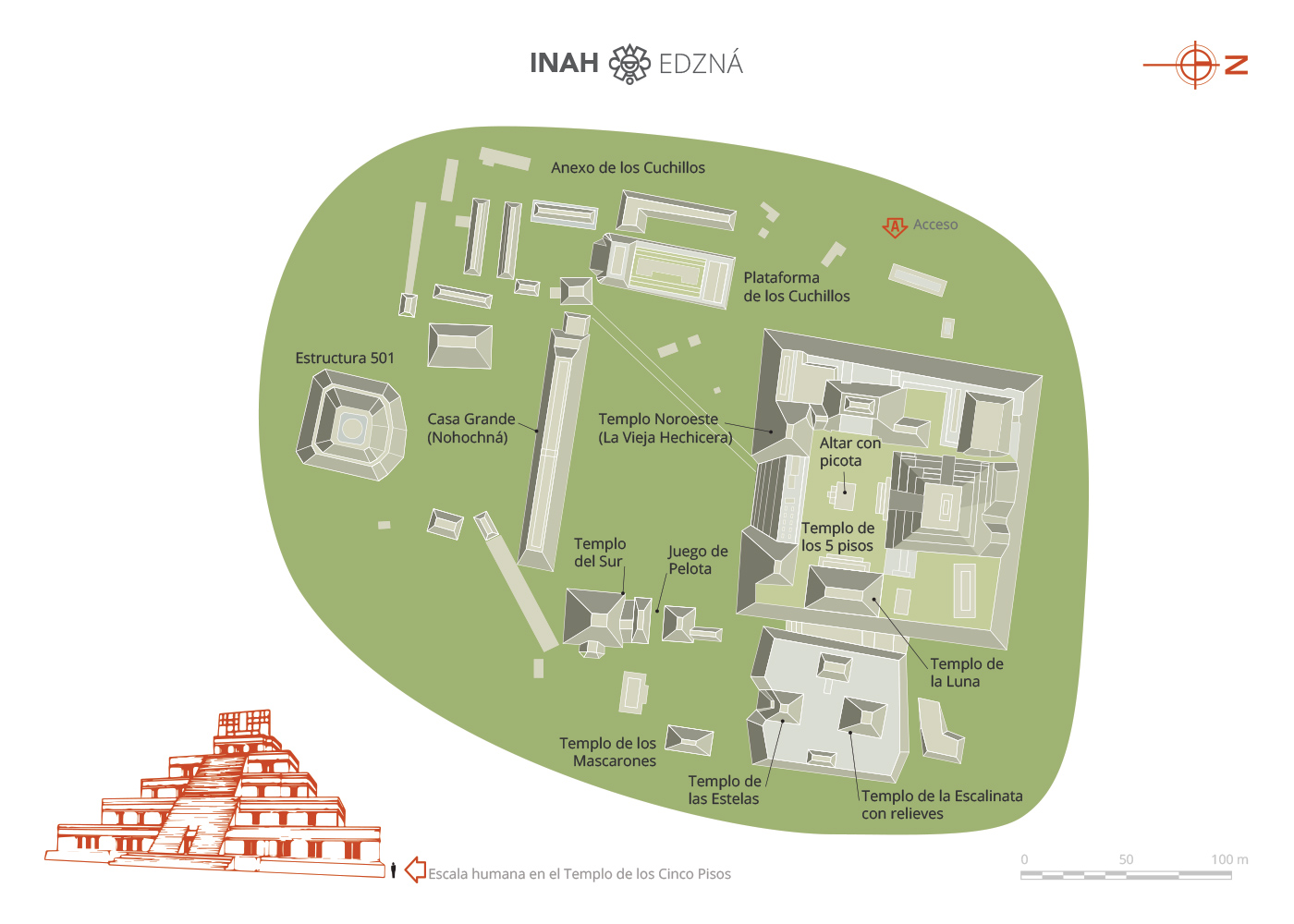

The construction of the water management system ensured the availability of this vital liquid for various practical purposes, particularly agriculture and subsistence during the different seasons. This also made it possible to produce the mortars required in the construction of the monumental buildings, which visitors can still admire today in various parts of the ancient city. The inhabitants later covered up these structures—which they considered sacred—with new constructions. This led to bulky volumes, as in the case of the Great Acropolis, an enormous construction reflecting the site’s great economic, political and religious power, and over which other monumental temples were built.

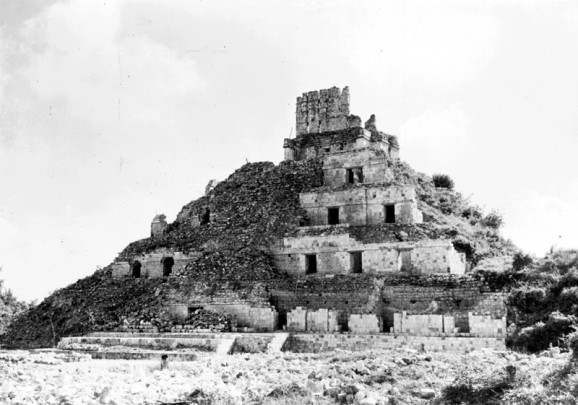

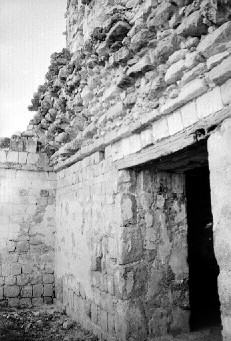

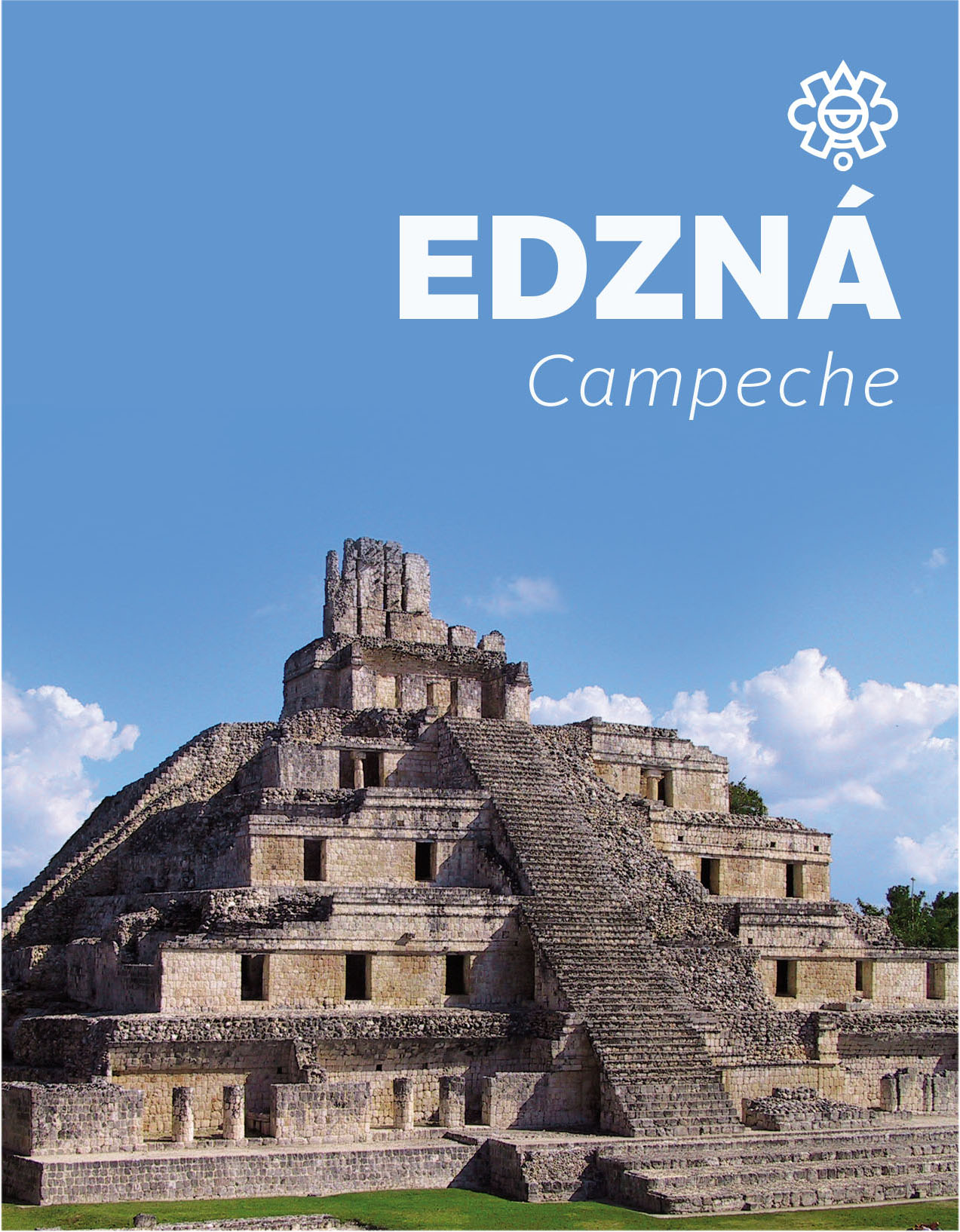

The Building of the Five Floors (BFF) stands out from the other structures in the central part of the eastern side of the Great Acropolis. This construction owes its name to the five levels that are visible on its eastern side, each one with vaulted chambers. The BFF rises up 118 feet from the level of the eastern plaza, making it one of the highest points in the Edzná valley. The original temple was partially demolished to build the building currently visible with its roof comb. This west façade dates back to the ninth century AD and it was the last section added to the plinth. The north side of the BFF shows the characteristics of the Petén architectural style: it was covered with wide, convex slabs in the Postclassic period (800-1200 AD). The roughly hewn central steps were added in the Postclassic. The eastern side of the BFF bears the mark of a similar process, only that there the beginnings or footing of the pyramid’s base can be seen, meaning that later it was covered by the Great Acropolis. The bottom of this plinth could have measured 260 by 260 feet.

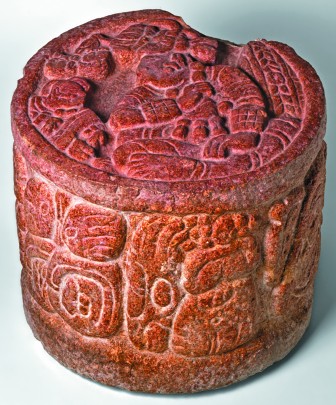

We know of 33 stelae at Edzná: four were carved between the years 41 and 435 AD; eleven are inscribed with glyphs that date them between 633 and 830 AD; the others are from the ninth and tenth centuries. Almost all of them show governors wearing luxurious garments that celebrate an enthronement, participation in the ballgame, the subjugation of a region, an alliance with another political center, and so on. Recent studies have included the reading of two iconic glyphs for Edzná (city and territory), and ten governors’ names, including one who was a woman.

The name by which this large collection of Maya remains is known today seems to have been derived from the final centuries of its pre-Hispanic occupation, when it might have been called Ytzná. This is a word from Chontal Mayan and means “house or place of the Itzá”; in other words, a settlement in which a family called Iztá once governed. In fact, this name continues to be used as a surname in many parts of the Yucatán peninsula. Over time “Ytzná” turned into “Etzná” and in the mid-twentieth century a further change made it Edzná.

However, the city did not always bear this name. The study of the hieroglyphs at the site has revealed two specific signs used to refer to the place. A toponym that refers to the center of the settlement represents the rattle of a snake. It could also refer to the Pleiades, a star cluster recorded by Maya astronomers. The word “tzab” was used to refer to the rattlesnake and also this cluster of stars. Meanwhile, the Edzná glyph shows a profile of a human face wearing an ear flare with crossed bands. It was used to mark the ancient city’s sphere of political and territorial rule. Both hieroglyphs were used between the seventh and ninth centuries of the Common Era.

The earliest references to Edzná are attributed to Teobert Maler, an Austrian explorer who came to Mexico as part of the militia attached to Maximilian of Habsburg in the 1860s, and then decided to remain in Mexico. Maler reached a point just 6 miles to the south of Edzná in 1887, but decided not to visit the ruins because he was informed that none of the “building façades were still standing."

Local farmers and hunters in the region had long been aware of these pre-Hispanic ruins, but it was not until 1906 when the inhabitants of Finca Hontún (four miles to the northeast of Edzná) reported its existence to the government of Porfirio Díaz. This news was lost in the chaos of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), and it was only in 1927 that the site was officially recognized thanks to Nazario Quintana Bello, Inspector of Pre-Hispanic Monuments for the country’s Ministry of Education. That same year, explorations of the site began, led by José Reygadas Vértiz (photographs), Federico Mariscal (plans and drawings), Enrique Juan Palacios and Sylvanus Morley (inscriptions and dates).

In 1943 Alberto Ruz Lhuillier and Raúl Pavón Abreu commenced work to discover the extent and distribution of the buildings. In 1958 César Sáenz, Héctor Gálvez and Raúl Pavón began their excavations and restoration of some sectors of the Great Acropolis. In the late 1960s George Andrews and a group of US architects (University of Oregon) drew up the first topographical map and undertook an architectural analysis of the site. At the start of the following decade, Ray Matheny, Donald Forsyth and other specialists (New World Archeological Foundation/Brigham Young University in Utah) conducted further explorations, preparing a second map as well as carrying out research into the ceramic materials and chronology of the site. Excavation and restoration work continued in the 1970s under the supervision of Román Piña Chán.

In 1981 and 1982 many communities in northwestern Guatemala ware gravely affected by the many clashes between the guerrilla forces and the army. Thousands of peasant farmers emigrated to Chiapas and eventually to Campeche. After 1986, the UN and the Mexican government implemented a job-creation program for those displaced by the conflict, and they worked on excavating, restoring, and maintaining Edzná’s archeological heritage. Luis Millet Cámara directed the project for the first two years, supported by a team of archeologists that included Florentino García, Heber Ojeda and Vicente Suárez, among others. Since 1988, Antonio Benavides C. has coordinated various research projects at Edzná, working together with many specialists such as Rosario Domínguez, Alan Maciel, Sara Novelo, Carlos Pallán and Ana María Parrilla. Beween 1996 and 2000 the program received European Union funding, and since 2000 the field seasons have been supported and funded by the INAH. After the past decade of archeological work, the public are now able to access some twenty buildings scattered over an area of 22 acres.

- Specialists suggest that adjustments were made to the Maya calendars here during the Classic period in the north and south of the Maya area.

- Crops found in this area include maize, squash, amaranth, nopal, yuca and chile, cultivation of which dates back to before the start of the Common Era.

-

+52 (981) 816 8179

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

FACEBOOK

-

TWITTER