It was the biggest pre-Hispanic settlement in North-Central Mexico; no other achieved its monumental scale. It was active from the fourth to the twelfth centuries of the Common Era and at its peak (from 600 to 850) it was a governing center which controlled 220 surrounding settlements. It had a network of roads, paved with slabs over a firmly compacted clay infill. They connected to areas which supplied natural resources such as clay deposits, timber and vegetation, as well as manufacturing workshops, farming villages or sanctuaries for religious processions. In other words, these pre-Hispanic roads had various uses.

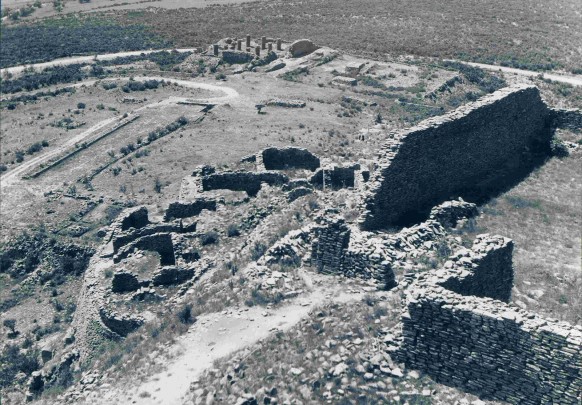

The site came to have a complex hierarchical organization and its architectural diversity testifies to the different areas of social power, such as housing for the elite, palaces, temples or public squares and ballgame courts, which could be accessed by people of different social status.

Various hypotheses have been put forward regarding the site’s origin and the background of its inhabitants. At first, it was believed that as well as groups of successor tribes of hunter gatherers from the north, settlers from Teotihuacan or people linked to this city may have lived here. Perhaps it had a defensive use against Chichimeca invasions. It may also later have become the capital of the Caxcan people, or a federation of this and other northern ethnic groups. By the time of the Spanish Conquest, it had been uninhabited for centuries.

In 1615, the evangelist and historian Fray Juan de Torquemada identified the site as one of the places where the Nahua people stopped during their pilgrimage from the north, and in 1780, the Jesuit priest Francisco Clavijero thought he saw Chicomóztoc (“place of seven caves”) in La Quemada, where the Seven Nahuatlaca Tribes came from. Thanks to the excavations and studies which began in the 1980s, it was possible to determine the archeological site’s timeline as beginning the Classic and Early Postclassic periods, developing in parallel to that of the neighboring Chalchihuite culture.

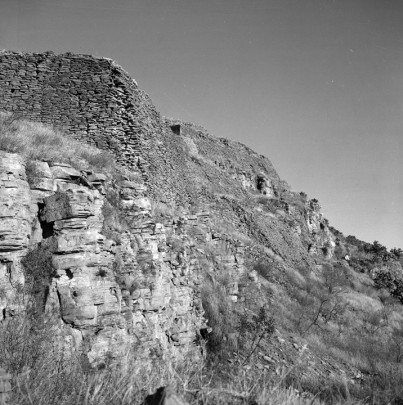

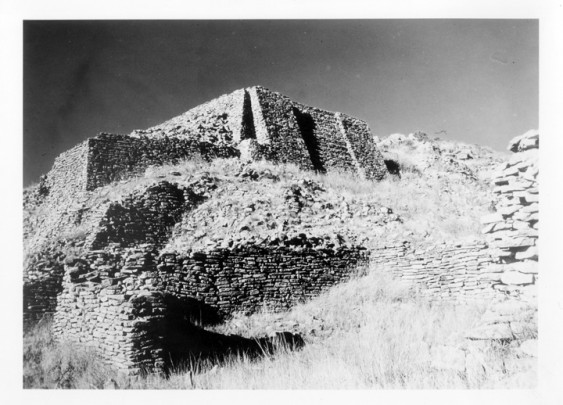

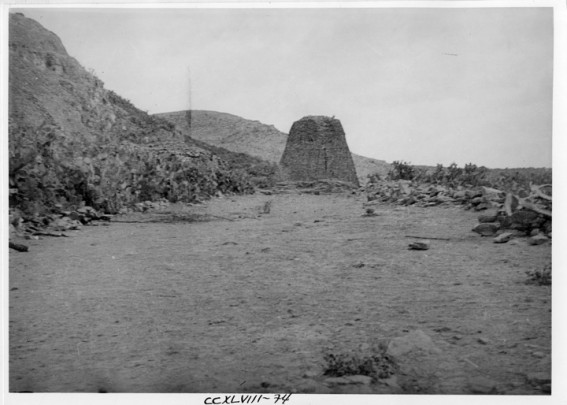

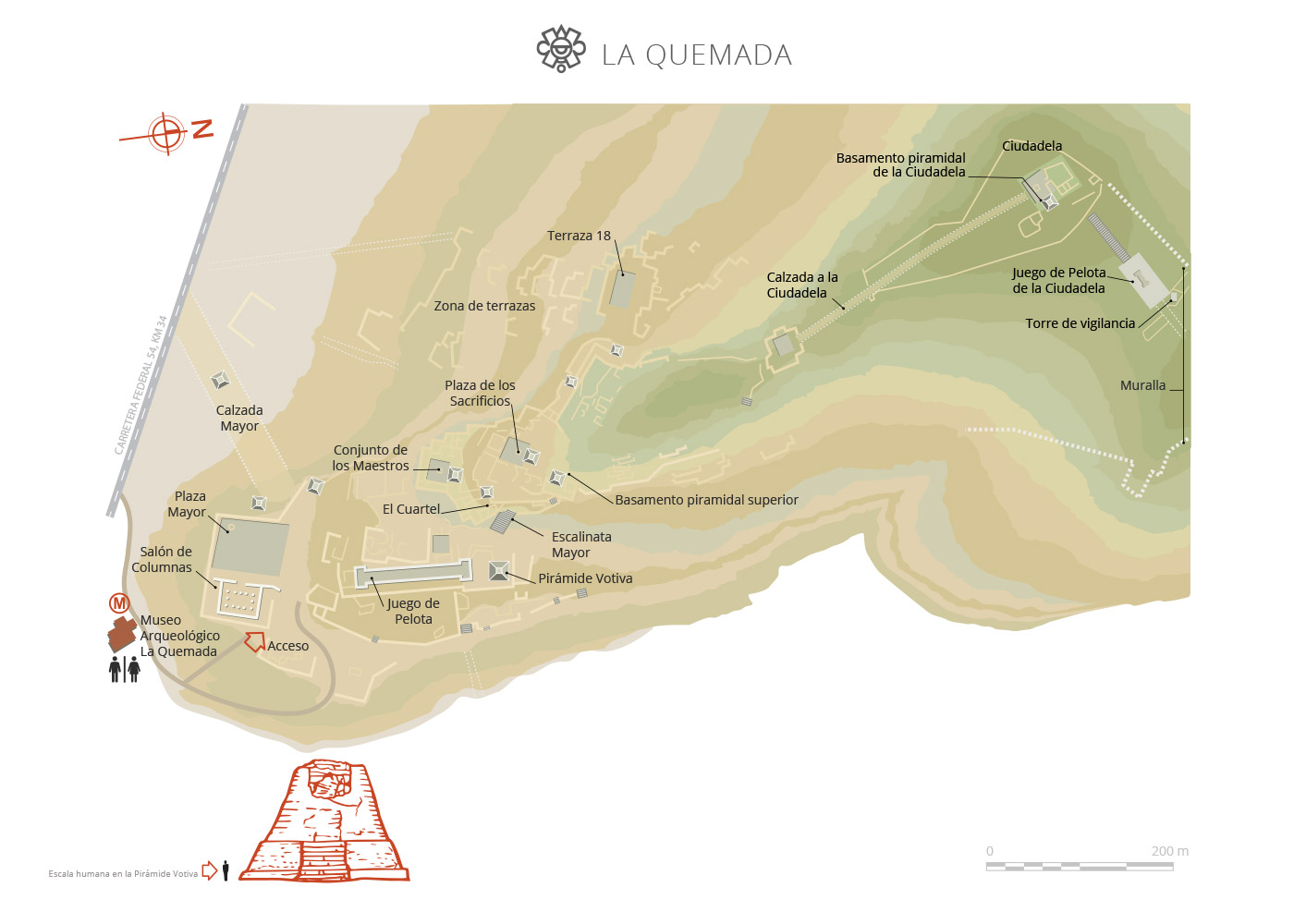

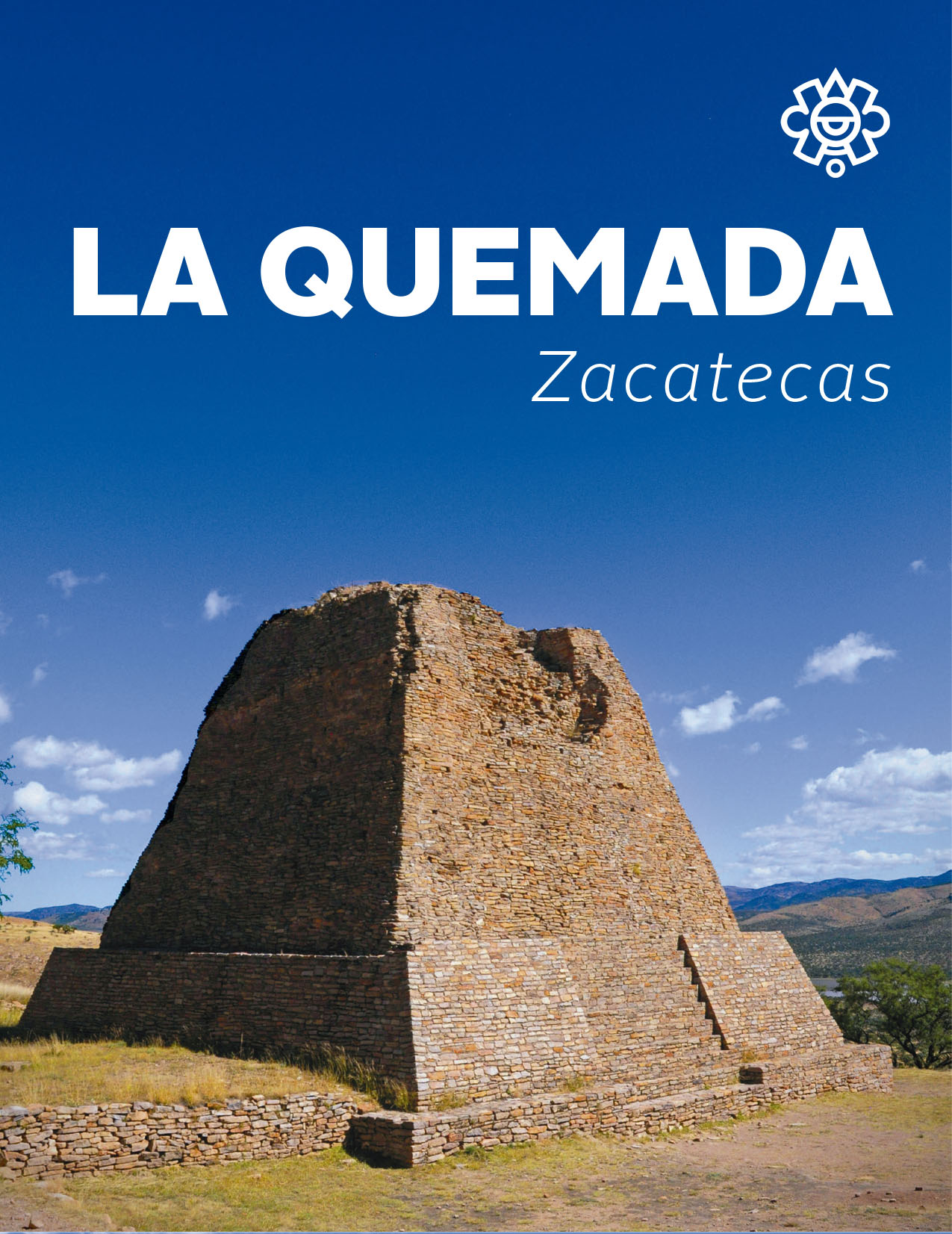

La Quemada contains structures far greater in size than any other archeological site in the region. For example, La Ciudadela (“The Citadel”), a complex surrounded by an 2,626 feet wall to the north, with walls measuring 20 feet in height and 13 feet in width; el Salón de las Columnas (“The Hall of Columns”), which extends over an area of 134 by 105 feet and may have had a roof 20 feet in height, or the Ballcourt, which at 262 by 49 feet is the largest in the area, with lateral walls of 10 and 16.5 feet in height. The Pirámide Votiva (“Votive Pyramid”) may be added to the list, with its sloping walls that are 33 feet in height, and the remains of a staircase which has collapsed at the top, where there used to be a temple. The housing areas consisted of a sunken courtyard with a temple overlooking them, like in Mesoamerica.

All of these structures were raised on platforms and terraces built on the hill of La Quemada, and the walls and columns are elegantly constructed with slabs of volcanic rock known as porphyritic rhyolite. In turn, these were coated with a clay stucco and possibly a mural decoration which has been completely lost, but can be deduced from other ancient pre-Hispanic cities. On some walls it is still possible to see the polished lime whitewash, whcih gives the city its overall appearance of elegance.

Nowadays, we know that La Quemada was an urban pre-Hispanic settlement which controlled the Malpaso valley and extended its trade network to the canyons of Southern Zacatecas, the region of Tunal Grande, the Altos de Jalisco and part of present-day Guanajuato and Michoacán.

- At different times, the site has been known as Tuitlan, Chicomoztoc, Coalcamatl, Cerro de los Edificios and La Quemada.