Monte Albán

Pre-Hispanic name unknown or the Hill of the Jaguar

The great Zapotec capital, on the flattened top of a group of hills, where the populace lived on the hillsides. Marvellous monuments, burial sites, ceramics, gold jewellery and fine stones. A rival of Teotihuacan, it was invaded by this empire, but survived to leave this amazing legacy.

About the site

Monte Albán was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. This ancient Zapotec capital crowns the Cerro del Jaguar (Jaguar Hill), 4,921 feet above sea level. Its main plaza was artificially levelled, measures 328 yards long by 197 yards wide, and has a capacity of up to 15,000 visitors.

Other hills and sites, such as Atzompa, Cerro del Gallo, El Plumaje, Monte Albán Chico and El Mogollito, were incorporated into its sphere of influence from Period II onward (200 BC to 200 AD). During this time, Monte Albán expanded and consolidated itself as a state, eventually reaching a population of approximately 35,000. This site was the longest occupied in Mesoamerica (500 BC to 900 AD) and was one of the first states, as its origins predate those of Teotihuacan.

The archeological site covers more than eight square miles, but most of the population was concentrated into an area of two and a half square miles. Its main plaza lies on the highest part of the hill, around which run natural and artificial terraces with residential structures on them. High-status residential units are near the center, which was also an area of religious and governmental activity, while lower status residences (related to agricultural and craft activities) are on the hillsides, especially to the north and east.

The pre-Hispanic structures consist of panels (vertical walls) and slopes (inclined walls), with raised sloping sections (alfardas) bordering the very wide stairways, thus giving the structures a great deal of solidity. One of the city’s architectural characteristics from the height of its splendor consists of double scapulary panels. Elite residences had a square base, with a central courtyard surrounded by rooms in hierarchical order. People were generally buried within residences, and the associated architecture and offerings tell us that their funerary customs were also based on hierarchy.

Monte Albán was the capital of a state that exacted tribute in kind (e.g. corn, beans and squash) from the communities it controlled. Merchants from different villages travelled to the city to exchange different goods. The city was also a center for the production of ceramics such as urns, a striking example of which is the depiction of Cocijo, god of lightning and rain. Its most noteworthy discoveries include carved stones (the Dancers, Conquest Slabs and Stelae of Governors), some of which bear evidence of Zapotec writing.

The relationship with Teotihuacan became very important from 200 to 500 AD. Evidence of a Zapotec neighborhood in Teotihuacan is one sign of this, as is the influence of Teotihuacan on the ceramic style of Monte Albán. Despite the site’s fall, people visited it from different places to leave offerings, as it was still considered a sacred site.

Other hills and sites, such as Atzompa, Cerro del Gallo, El Plumaje, Monte Albán Chico and El Mogollito, were incorporated into its sphere of influence from Period II onward (200 BC to 200 AD). During this time, Monte Albán expanded and consolidated itself as a state, eventually reaching a population of approximately 35,000. This site was the longest occupied in Mesoamerica (500 BC to 900 AD) and was one of the first states, as its origins predate those of Teotihuacan.

The archeological site covers more than eight square miles, but most of the population was concentrated into an area of two and a half square miles. Its main plaza lies on the highest part of the hill, around which run natural and artificial terraces with residential structures on them. High-status residential units are near the center, which was also an area of religious and governmental activity, while lower status residences (related to agricultural and craft activities) are on the hillsides, especially to the north and east.

The pre-Hispanic structures consist of panels (vertical walls) and slopes (inclined walls), with raised sloping sections (alfardas) bordering the very wide stairways, thus giving the structures a great deal of solidity. One of the city’s architectural characteristics from the height of its splendor consists of double scapulary panels. Elite residences had a square base, with a central courtyard surrounded by rooms in hierarchical order. People were generally buried within residences, and the associated architecture and offerings tell us that their funerary customs were also based on hierarchy.

Monte Albán was the capital of a state that exacted tribute in kind (e.g. corn, beans and squash) from the communities it controlled. Merchants from different villages travelled to the city to exchange different goods. The city was also a center for the production of ceramics such as urns, a striking example of which is the depiction of Cocijo, god of lightning and rain. Its most noteworthy discoveries include carved stones (the Dancers, Conquest Slabs and Stelae of Governors), some of which bear evidence of Zapotec writing.

The relationship with Teotihuacan became very important from 200 to 500 AD. Evidence of a Zapotec neighborhood in Teotihuacan is one sign of this, as is the influence of Teotihuacan on the ceramic style of Monte Albán. Despite the site’s fall, people visited it from different places to leave offerings, as it was still considered a sacred site.

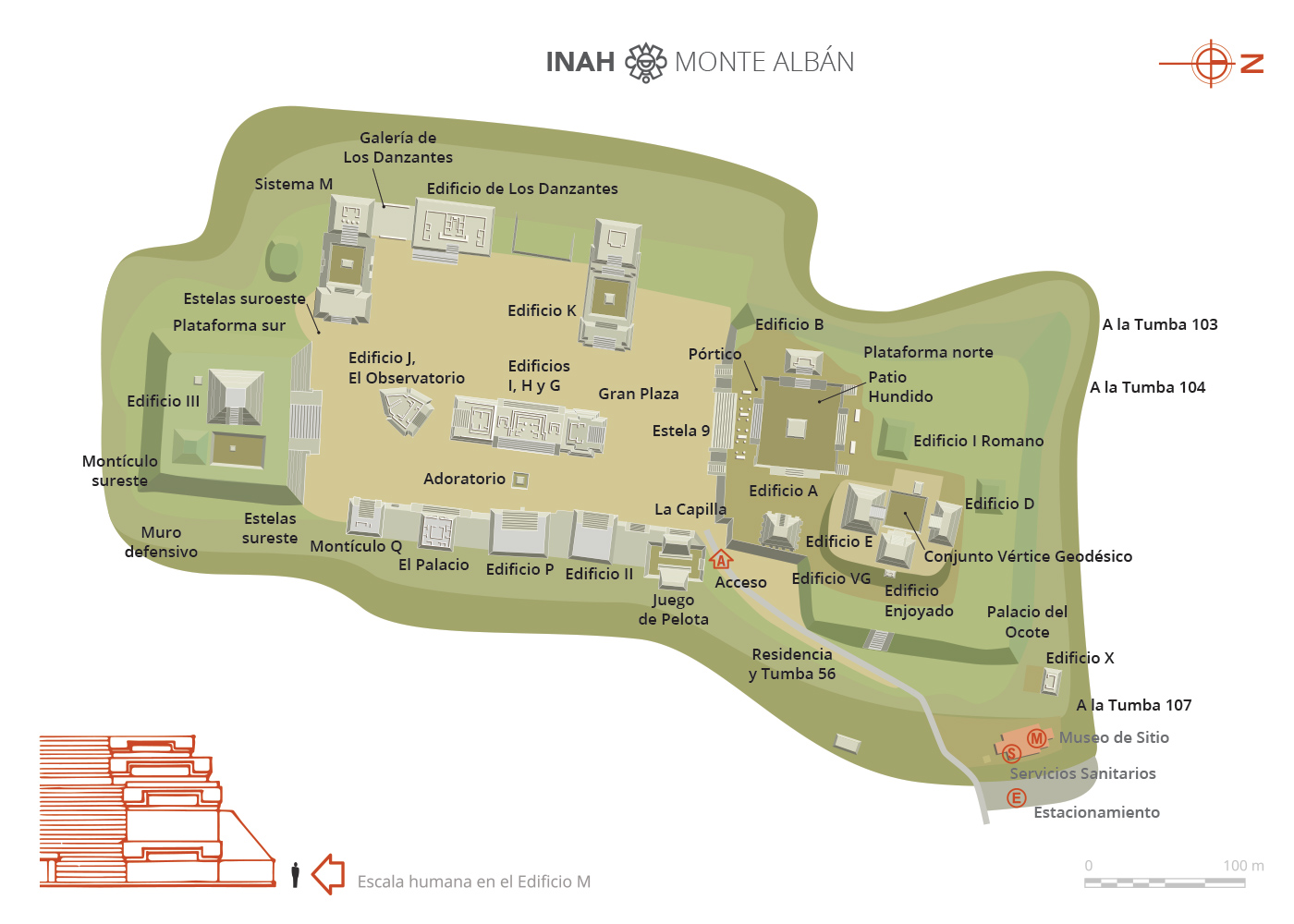

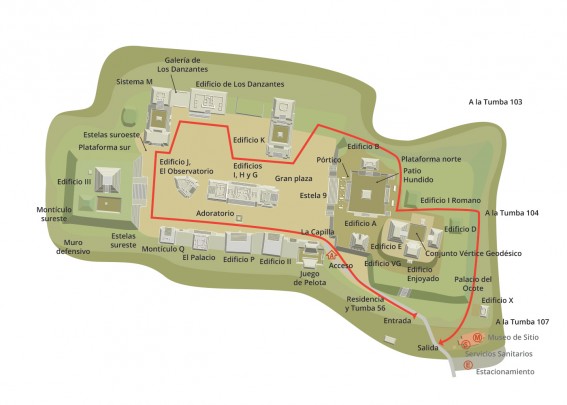

Map

Did you know...

- Monte Albán’s protected area covers eight and a half square miles and includes three hills: that of Monte Albán, El Gallo and Atzompa.

- The Wall of the Dancers and Building J were built with large monoliths, as was the wall of Mesoamerican ballgame players in Dainzú.

- In 200 AD, a group of families who were possibly from Monte Albán established a Zapotec neighborhood on the western side of Teotihuacan, about two miles from the Avenue of the Dead. Although relations were initially peaceful between the two cities, the inhabitants of Teotihuacan conquered Monte Albán in approximately 350 AD and settled on the North Platform.

- The palace above Tomb 105, on the eastern side of the access road, was an elite residence and may have been occupied by the last ruler of Monte Albán.

- Tomb 7 is one of the best known archeological finds in Mexico. It was built and used during the Classic period. Centuries later, it was reused by a royal family who were perhaps of Zapotec and Mixtec descent to hide the family treasure (gold, jewels and carved bones).

- A large circular wall was built on the South Platform in the Postclassic period, after Monte Albán had been abandoned. This was used as a fortress by people who lived on the valley floor, perhaps in what is now Xococotlán.

An expert point of view

Jesús Eduardo Medina Villalobos

Zona Arqueológica de Monte Albán

-

+52 (951) 516 70 77

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

FACEBOOK

Directory

Directora de la Zona Arqueológica

Patricia Martínez Lira

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (951) 516 9770 y 501 2311

Área de Difusión y Servicios Educativos

Eric Valentín Flores Ramírez

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (951) 516 9770 y 501 2311

Área de Conservación e Investigación

Jesús Eduardo Medina Villalobos

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (951) 516 9770 y 501 2311

Encargada de Difusión

Yuridia Inelva Ríos Gómez

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (951) 516 97 70; +52 (951) 501 23 11