Monte Albán, an archeological site occupying a central position in the Valley of Oaxaca, was the civic and administrative capital of Zapotec society for a period of nearly 1,300 years: from its founding in 500 BC to its decline as the valley’s ruling political entity at the end of the Classic period, between 800 and 850 AD.

The funerary practices of the Zapotec people are one of Monte Albán’s most interesting aspects, as most people were buried in different places within residential units. These places could be stone tombs, cists (graves consisting of four lateral slabs with a fifth as a lid) dressed with tiles and bricks, graves excavated from the bedrock, domestic spaces such as storage pits, ovens and dumpsites reused as funerary areas, or often in holes or pits in the floor surfaces of rooms.

Of the aforementioned examples, tombs were Monte Albán’s most representative type of funerary architecture. So far, a total of 249 tombs have been discovered in different sections of the archeological zone. These were formal constructions for housing the human remains of the most important individuals from each family. They have been classified into three types based on architectural analysis: 1) rectangular tombs, with adobe or stone walls on all four sides, accessed through the roof; 2) rectangular tombs with an antechamber and a main chamber, which have vaulted ceilings and niches in the walls around the chamber; and 3) cross-shaped tombs with flat ceilings whose main chamber sometimes has niches in its walls.

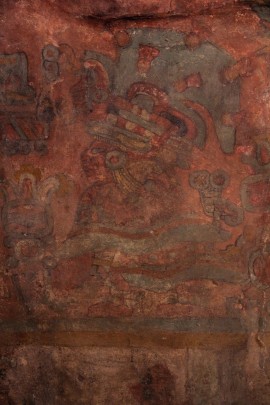

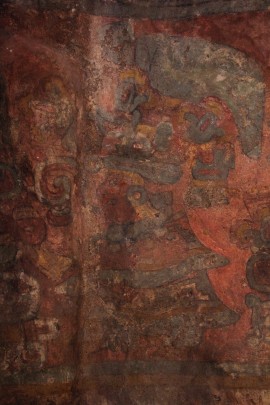

Moreover, the development of mural painting in Monte Albán focused on funerary architecture, which provided a canvas for displaying the complex system of religious beliefs associated with life and death. These murals generally depicted a procession of richly attired figures performing complicated funerary rites, who have in turn been interpreted as direct ancestors of the individuals deposited within the tombs.

Preserving these tombs is therefore extremely important, which is why they are unfortunately closed to the public. To compensate for this, a number of activities are programmed in order to display the mural paintings.

One noteworthy example of funerary architecture is Tomb 105. It was discovered by Alfonso Caso in 1937, during the sixth season of the Monte Albán Project explorations. The tomb lies in one of the archeological zone’s largest palatial residences, northeast of the main plaza. It corresponds to Period IIIB-IV (700-800 AD), and displays the same classic style of Zapotec pictorial representation that had already been consolidated in the murals of Tomb 104.

This is a cross-shaped tomb which has a chamber and a main antechamber that is accessed from the west, while the back faces east. As with Tomb 104, the funeral chamber was excavated from the bedrock of the hill, which was smoothed and covered with a stucco coating that served as a support for the paint, although in this case the surface of the walls is not regular but has a rougher finish.

The tomb is mainly decorated inside the funeral chamber, where pigments have also been applied to the ceiling and floor, although the main motifs were painted on the side and back walls, creating a general scene that can be divided into three horizontal sections: 1) the upper section repeats a rectangular panel that recalls a double scapulary panel, typical of Zapotec architecture, below which lies the motif of the “celestial jaws,” which serves to contextualize the scene within a sacred space; b) the central section shows 18 richly attired individuals who share certain characteristics: all are shown with their torsos facing forwards and their faces in profile, and all (bar one female figure) appear to be elderly, as they are depicted as wrinkled or toothless; the women are barefoot and wearing quexquémetl (shawls) and skirts; the men are wearing sandals and holding sticks, bags of copal or grain which they are scattering on the ground; in front of each individual there is also a calendar glyph that probably corresponds to the figure’s name; 3) finally, the bottom section consists of a border decorated with pairs of rectangles with rounded corners that alternately rise and fall.

Based on the context and the scene reproduced in the mural painting, some scholars have interpreted the figures depicted as ancestors belonging to a high social class, who are carrying out a religious ceremony or a funerary rite, and are related to the individual who was originally deposited within the tomb.