Western Mexico

The ancient inhabitants of this vast territory occupied much of the Pacific coast in a region covering the modern-day states of Sinaloa, Nayarit, Jalisco, Colima, Michoacán and parts of Guanajuato and Guerrero. The most ancient remains, dating back as far as 1800 BC, have been found mainly in isolated settlements in Michoacán and Jalisco.

Chupicuaro culture developed during the Late Preclassic (400 BC- 200 AD), spreading from Guanajuato westwards, to the north and the Central Highlands following the course of the river Lerma. This tradition has left tombs cut directly into the earth and offerings with a notable presence of female figures, referring to the cult of maternity as well as to the fertility of the earth.

The West was a connecting point that encouraged the exchange of cultural practices and the commercial circulation of materials such as turquoise, and the migration of different ethnic groups from the periphery towards the Central Highlands. During the Early Classic (200-650) sites such as Tingambato had aspects that reflected their connection with Teotihuacan’s sphere of influence. In the Classic period the West can be seen as the backdrop to three significant cultural traditions: Tierra Caliente (Hot Land), Shaft Tomb and the Bajio. These cultures are marked out by a craft production based on clay and shell, stonework and metalwork with a high degree of specialization and a wide range of subjects.

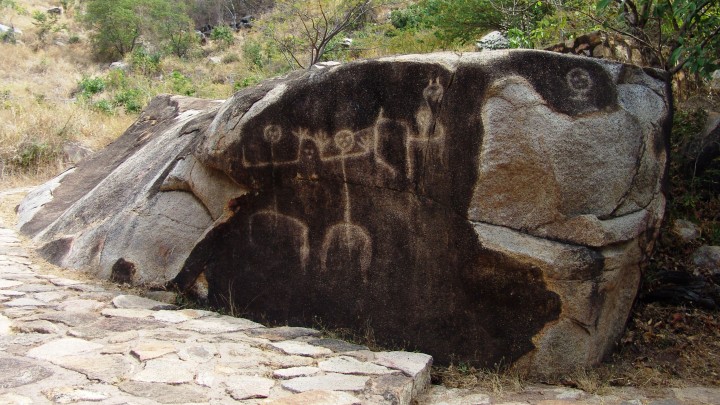

Tierra Caliente cultures are closer to Mesoamerica than the West and sometimes reflect marked Teotihuacan influence. This tradition developed along the length of the Balsas river to the Mezcala region in the center of Guerrero and even in archeological sites such as La Organera Xochipala. The settlements feature very tall pyramid structures, plazas and ballcourts, as well as carvings on hard stone.

Shaft Tomb culture on the other hand arose between 200 and 600 AD in the modern states of Colima, Jalisco and Nayarit. This culture was distinguished by the custom of burying the most distinguished members of the community, such as the rulers and their family, in shaft tombs and chambers which consisted of vertical wells connecting to one or more vaulted chambers. Tombs were occasionally reused and rich offerings have been found with objects from a range of materials including clay figures, shell ornaments, grinding stones, spindle whorls, projectile tips made from obsidian or stone, axes and musical instruments. In this tradition buildings were made from perishable materials such as palm and adobe, on top of small stone platforms. The archeological site of Guachimontones in the Teuchitlan region is one of the main examples of the building design of rectangular and circular plan houses.

We have little information on the Bajio cultures, which grew out of a tradition based on Chupicuaro culture, with sites such as El Coporo whose architecture consists of terraces built on hillsides and extensive platforms with vestiges of rooms and columns built from mud and stone.

The use of shaft tombs was abandoned after 600 AD and regional developments came to the fore, notably at sites like Ixtlan del Rio and El Chanal. Around 900 the West displayed cultural influence from the Central Highlands tradition, such as the Toltecs and the Mixteca-Puebla. Settlements with a marked militaristic outlook can be seen, with elements such as building complexes around plazas, platforms, altars and sunken patios dedicated to deities such as Quetzalcoatl, Xipe and Tlaloc.

The Postclassic (900-1521) was the period in which Purepecha culture flourished, when this group held sway over Michoacán and some neighboring areas, extending to the borders of the Mexican empire. Around 1325 the ruler Tariacuri consolidated Tarascan political and military power, establishing his capital at Patzcuaro, which made it easier to retain absolute control of the lake shores. By 1450 Tzintzuntzan had become the most important city of the Tarascan kingdom, and its domination lasted until the arrival of the Spanish.

The West is the area with the earliest evidence of metal objects and during the Postclassic it was distinguished by significant metallurgical development with practical use in tree felling, wood working, working the land, fishing, hunting and warfare. Copper, gold, silver, tin, lead and possibly also bronze were worked into ornaments such as discs, rattles, ear flares, beads, rings, pendants and bracelets, as well as tools for making holes.