Contrary to what we might expect, this ancient settlement has many archeological remains distributed across practically the whole of the mountainous terrain, extending up to the neighboring Cerro Chihuahua. These remains include a monument complex covering the whole summit of the Cerro de las Ventanas.

There are remains of shaft tombs dating to the first centuries AD very close to the mountainside. This was a sedentary society which practiced agriculture. Since the Cerro de las Ventanas is surrounded by a curve of the Juchipila River, it is probable that the cultivation of crops was one of the principal activities of the ancient inhabitants, making use of the river banks for this purpose.

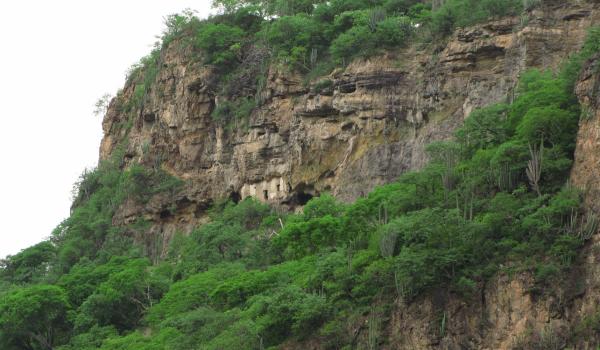

Various terraces and platforms have been found on the east side of the mountain slopes. These modified the terrain by countering the slope to create flat spaces for dwellings and possibly for cultivation. Adaptations of this nature can also be seen in other areas of the mountain, serving as the foundations for building complexes used for ceremonies between the seventh and fifteenth centuries.

Topographical adaptation for architectural purposes altered the appearance of the mountainside, building a cultural landscape which served as a place of worship for at least seven or eight centuries.

Several human burials of different periods have been uncovered on the lower parts of the mountainside with grave goods and offerings consisting of sea-shell bracelets, pots, clay figurines and copper ornaments in later burials.

Human occupation was interrupted a couple of centuries before the arrival of the conquistadors, although the region continued to be inhabited by Caxcan groups.

The region was known as Xochipillan, or the place of the flowers, possibly because of its fertile soil. Around 1530 Cristóbal de Oñate founded the modern town of Juchipila close to a settlement known as Tlatlan or Tlaltan. The Caxcan were tired of the abuses of the Spanish and in 1541 they led an indigenous rebellion which threatened the conquest of New Spain. The episode ended in the famous battle of Cerro del Mixton, which the Spanish won.

There has been relatively little research into the Cerro de las Ventanas. One of the few exceptions was the photographic work of the Czech anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička, who documented the site’s emblematic remains in 1902, without excavating them. Many decades later, between 1988 and 1991, the U.S. archeologist Elizabeth Mozzillo carried out surveys and excavations which included taking samples for radiocarbon dating, which gave results from between the years 20 to 1405 AD.

A complex of terraces to the east of the site was explored between 2002 and 2006, as well as topographical surveys of the highest part of the Acropolis. They were directed by Dr. Nicolás Caretta. Subsequently, between 2008 and 2010, the archeologist Armando Nicolau Romero undertook some research and as part of his role he carried out some minor maintenance. Later, Marco Santos Ramírez took over responsibility, partially clearing the Plaza de los Altares.

Since mid-2014 Cerro de las Ventanas has been the focus of a comprehensive research and conservation project managed by the Zacatecas office of the INAH, under the charge of the archeologists Laura Solar Valverde, Luis Martínez Méndez and Peter Jiménez Betts. Good work has also been done to make the archeological site more accessible to the public. A Visitor Services Center was designed and built as part of this project, establishing the basic infrastructure for the site’s operation and management. Currently, the site is temporarily closed.