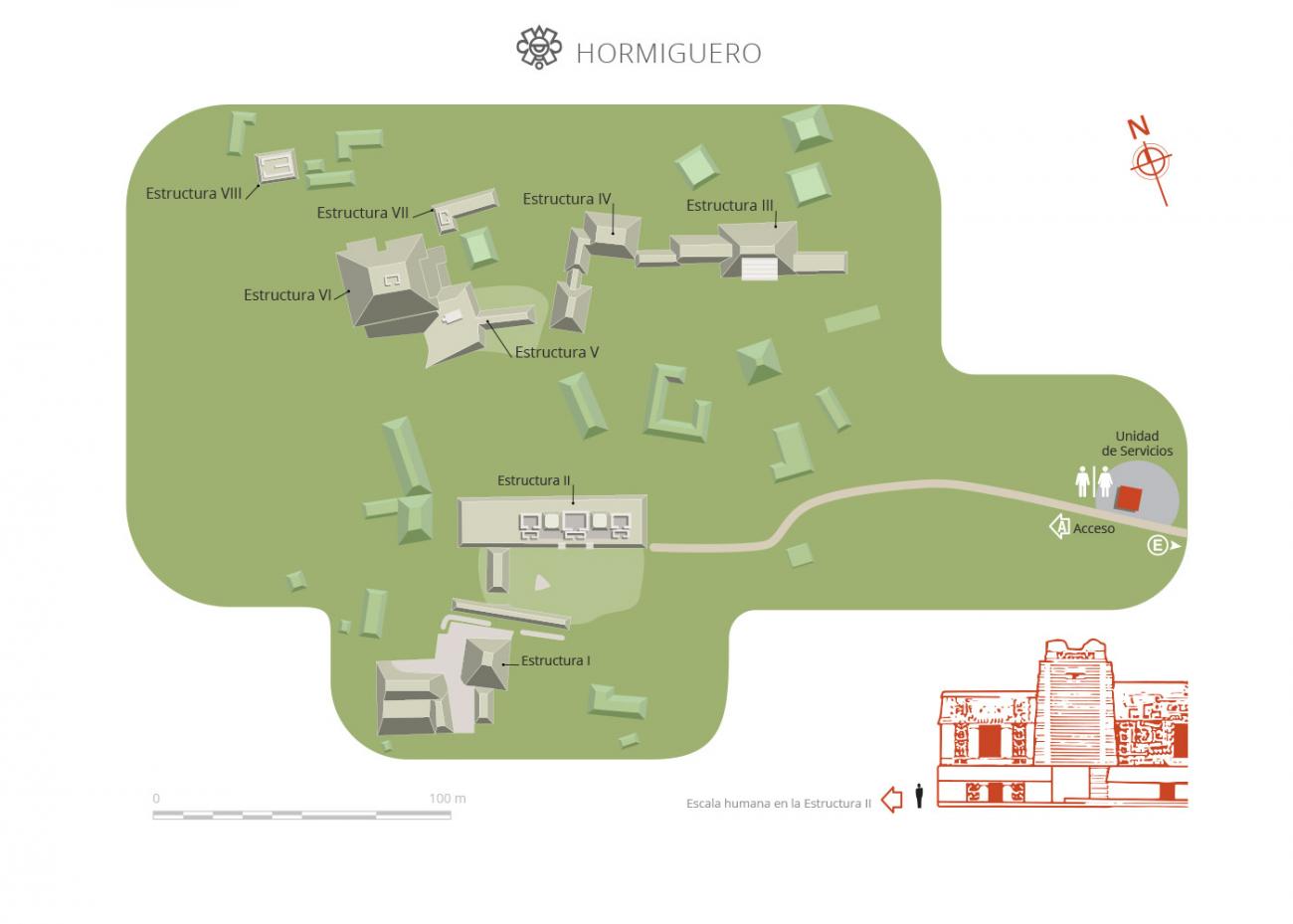

Ensconced in the heart of the southern jungles of the state of Campeche, El Hormiguero consists of around a hundred pre-Hispanic structures. It was reported in 1933 by the Americans Karl Ruppert and John Dennison, who named it El Hormiguero (“the anthill”) due to the large number of anthills found there. It was a Maya city of medium importance and subordinate to Becán, the principal city in the entire Río Bec region. The settlement was first inhabited at the beginning of the Common Era, during the Late Preclassic. In the Early Classic (300 AD) there already existed a small, self-sufficient community, and a century later this transformed from being a village to a more hierarchical society that built a number of monumental structures.

However, it was only in the Late Classic, in around 750 AD, when construction work intensified: the buildings became larger, had more refined finishes and bore more symbolic features, indicating a stratified society. Impressive structures with towers were erected during this period of the city’s development. For example, Structures 2 and 6 have an integrated zoomorphic entrance, while Structure 66 has a series of mask panels. Also, a particularly fine example of a tripartite facade has been preserved on Structure 2, as well as a large zoomorphic entrance with lateral towers.

The site was abandoned in around 950 AD and its buildings looted. By contrast, the population of Becán grew considerably, perhaps because it received the people who had left El Hormiguero and other Maya settlements in the region.

Since the 1970s, a number of archeological studies have begun to be carried out at El Hormiguero. Specifically, Agustín Peña of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) was in charge of early conservation works at the site. Between 1984 and 1985 the INAH initiated—under the supervision of Román Piña Chán and with Ricardo Bueno in charge of the team in the field—projects to excavate and consolidate Structures 2 and 5, which are now some of the few remains of the architectural features open to the public, with their zoomorphic entrances and a series of administrative or residential chambers.

Between 1991 and 1994, with Ricardo Bueno as director of a team of graduates from the National School of Anthropology and History (ENAH), work was resumed at El Hormiguero. Another INAH project was led by Ángeles Cantero from 1997 to 1998, focusing on previously unexplored parts of Building 2, and exploration of Structure 5 began. In 2001, archeologist Luz Campaña was in charge of conducting maintenance on the ceiling of the temple on top of this building. In late 2011, and during early 2016, Vicente Suárez of INAH’s regional office in Campeche carried out both small and large-scale interventions on Structures 2 and 5, which were showing signs of damage due to the ravages of time and a lack of upkeep. At the same time, the west facade of Building 6 was explored, consolidated and restored. In recent dates, Structure 7 was completely restored. The damage seen in Structures 2, 5, 6 and 7 of this archeological area were caused by exposure to the elements, encroaching vegetation, cracks and filtrations in the wall faces, causing ashlar stones to become detached, disintegration of mortar and sections of some walls to crumble.