Tulum

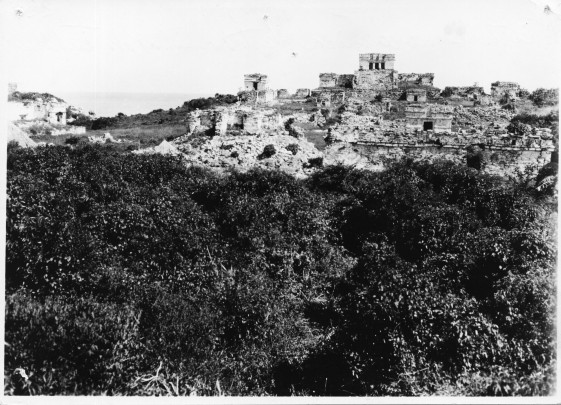

Walls/ramparts

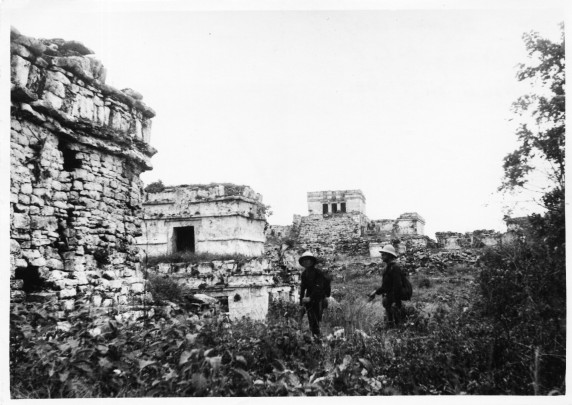

A powerful walled city on the coast, with some of the best preserved mural paintings in the Mayan area. Its monuments exemplify the particular style of the East Coast, where the ancient pointed arch gave way to flat roofs supported by columns.

About the site

The buildings that can be seen in Tulum today are from the Middle and Late Postclassic (1250-1550), the final period of pre-Hispanic occupation of the Yucatan peninsula. The presence of some elements corresponding to previous stages, such as Stela 1 which dates to 564, as well as Structure 59, which has some stylistic elements from the Terminal Classic, indicate that the city could have been founded in an older period, possibly under the control of nearby Tancah.

Archeological studies have consistently shown that Tulum was one of the principal Mayan cities from the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries. Its strategic location between the “kuchkabaloob” (Maya for provinces) of Cochuah and Cozumel, its setting at the highest point of the region and its effective defensive position ensured that it was a nodal point, well positioned to exploit the rich marine resources of the coast of Quintana Roo. Tulum might have been a “batabil” (Maya for independent city), free from the control of other states, practically until the arrival of the Spanish in the fifteenth century, when it was finally abandoned.

The architecture of its earliest buildings features some Puuc-style elements, but like the other structures of the east coast of Quintana Roo, Tulum is free from jonquils (semi-rounded Puuc columns) and mosaics. On the other hand it presents some unique features such as smooth surfaces, which were undoubtedly decorated with beautiful wall paintings, now lost.

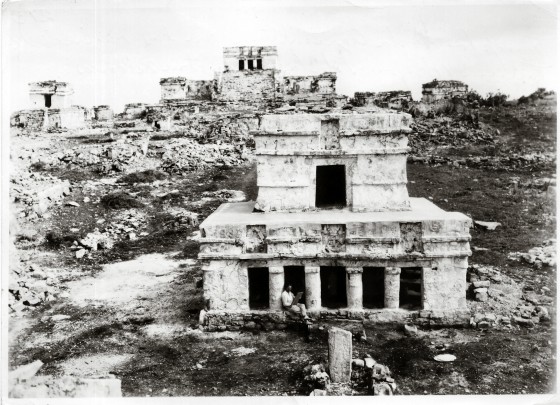

The Tulum region seems to have experienced significant population growth after the year 1200. At this time, the architects of the region perfected their own building style which later became very popular. It was certainly not until after 1400 that the majority of the area’s architectural projects were carried out, and when the style known by the archeologists as “East Coast” came into its own. This style is typified by the use of miniature temples, shrines within shrines (small buildings inside larger ones), buildings with intentionally collapsed walls, as well as palaces with colonnades and flat roofs, which replaced the vaulted coverings of the Mayan buildings of previous eras.

The adornment of the Tulum buildings includes niches over the door lintels, which nearly always featured a stucco representation of the diving god. The technique and religious content of the Tulum mural paintings were immensely complex. The outstanding feature is the presentation of human and animal figures in profile, whilst objects were presented from the front. According to some authors, the symbolic content of the Tulum paintings is concerned with cosmological themes linking to rebirth and the passing of beings from the underworld to a middle earth, where human and mythical traits come together, and where Venus and the Sun play very important roles. The researcher Arthur Miller has suggested that the sanctuaries of Tulum were dedicated to cosmological rituals in which pilgrims from various locations participated, and which were possibly related to long distance trade, the city’s principal source of wealth.

If this hypothesis is true, the sacred and the profane would have been indissolubly linked to the design and features of the walled city of Tulum, since trade would have been the basis for this city becoming a highly important ceremonial center and a notable seat of political power.

It appears that the name “Tulum” is relatively recent. It means a protective wall, enclosure or palisade, in allusion to the still-intact walls which encircle the group of monuments. The name Tulum seems to have been given to the city after it was abandoned or already in ruins.

The story of Tulum’s discovery is long and complex. In 1518, during Juan de Grijalva’s second expedition to the Mexican coast, the expedition’s chaplain and chronicler Juan Diaz wrote about having seen a city “as large as Seville,” which might well have been Tulum, which in those times was densely populated and was apparently the principal city of an independent province, a Mayan “batabil,” as mentioned above. The beginnings of the conquest, and eventual Spanish colonization of the Yucatan peninsula, had such a devastating impact on the region that when the “Relaciones de Yucatán” (Accounts of the Yucatan) were written by Juan de Reigosa in 1579, Tulum was described as a ruined settlement, and its splendor was a thing of the past.

Archeological studies have consistently shown that Tulum was one of the principal Mayan cities from the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries. Its strategic location between the “kuchkabaloob” (Maya for provinces) of Cochuah and Cozumel, its setting at the highest point of the region and its effective defensive position ensured that it was a nodal point, well positioned to exploit the rich marine resources of the coast of Quintana Roo. Tulum might have been a “batabil” (Maya for independent city), free from the control of other states, practically until the arrival of the Spanish in the fifteenth century, when it was finally abandoned.

The architecture of its earliest buildings features some Puuc-style elements, but like the other structures of the east coast of Quintana Roo, Tulum is free from jonquils (semi-rounded Puuc columns) and mosaics. On the other hand it presents some unique features such as smooth surfaces, which were undoubtedly decorated with beautiful wall paintings, now lost.

The Tulum region seems to have experienced significant population growth after the year 1200. At this time, the architects of the region perfected their own building style which later became very popular. It was certainly not until after 1400 that the majority of the area’s architectural projects were carried out, and when the style known by the archeologists as “East Coast” came into its own. This style is typified by the use of miniature temples, shrines within shrines (small buildings inside larger ones), buildings with intentionally collapsed walls, as well as palaces with colonnades and flat roofs, which replaced the vaulted coverings of the Mayan buildings of previous eras.

The adornment of the Tulum buildings includes niches over the door lintels, which nearly always featured a stucco representation of the diving god. The technique and religious content of the Tulum mural paintings were immensely complex. The outstanding feature is the presentation of human and animal figures in profile, whilst objects were presented from the front. According to some authors, the symbolic content of the Tulum paintings is concerned with cosmological themes linking to rebirth and the passing of beings from the underworld to a middle earth, where human and mythical traits come together, and where Venus and the Sun play very important roles. The researcher Arthur Miller has suggested that the sanctuaries of Tulum were dedicated to cosmological rituals in which pilgrims from various locations participated, and which were possibly related to long distance trade, the city’s principal source of wealth.

If this hypothesis is true, the sacred and the profane would have been indissolubly linked to the design and features of the walled city of Tulum, since trade would have been the basis for this city becoming a highly important ceremonial center and a notable seat of political power.

It appears that the name “Tulum” is relatively recent. It means a protective wall, enclosure or palisade, in allusion to the still-intact walls which encircle the group of monuments. The name Tulum seems to have been given to the city after it was abandoned or already in ruins.

The story of Tulum’s discovery is long and complex. In 1518, during Juan de Grijalva’s second expedition to the Mexican coast, the expedition’s chaplain and chronicler Juan Diaz wrote about having seen a city “as large as Seville,” which might well have been Tulum, which in those times was densely populated and was apparently the principal city of an independent province, a Mayan “batabil,” as mentioned above. The beginnings of the conquest, and eventual Spanish colonization of the Yucatan peninsula, had such a devastating impact on the region that when the “Relaciones de Yucatán” (Accounts of the Yucatan) were written by Juan de Reigosa in 1579, Tulum was described as a ruined settlement, and its splendor was a thing of the past.

Map

Did you know...

- The walled city is part of a large pre-Hispanic settlement to which the site of Tancah, two miles to the north, also belongs.

- It is the most representative and famous site of the coast of Quintana Roo.

- During the indigenous rebellion known as the Caste War (1847), the walled city became a sanctuary for the rebellious Maya.

An expert point of view

An exceptional site with well-preserved buildings, ornate wall painting and a striking setting overlooking the Caribbean.

Adriana Velázquez Morlet

Centro INAH Quintana Roo

Practical information

Monday to Sunday from 08:00 to 17:00 hrs. Last entry 15:30 hrs.

Cobro oficial en taquillas INAH $100.00 pesos

https://ventadeboletosenlinea.inah.gob.mx/

Se localiza al sur de Cancún, junto al poblado de Tulum, dentro del Parque Nacional Tulum.

Services

-

+52 (983) 837 24 11

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Directory

Encargado

José Manuel Ochoa

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.