Toluquilla

Hunchback hill

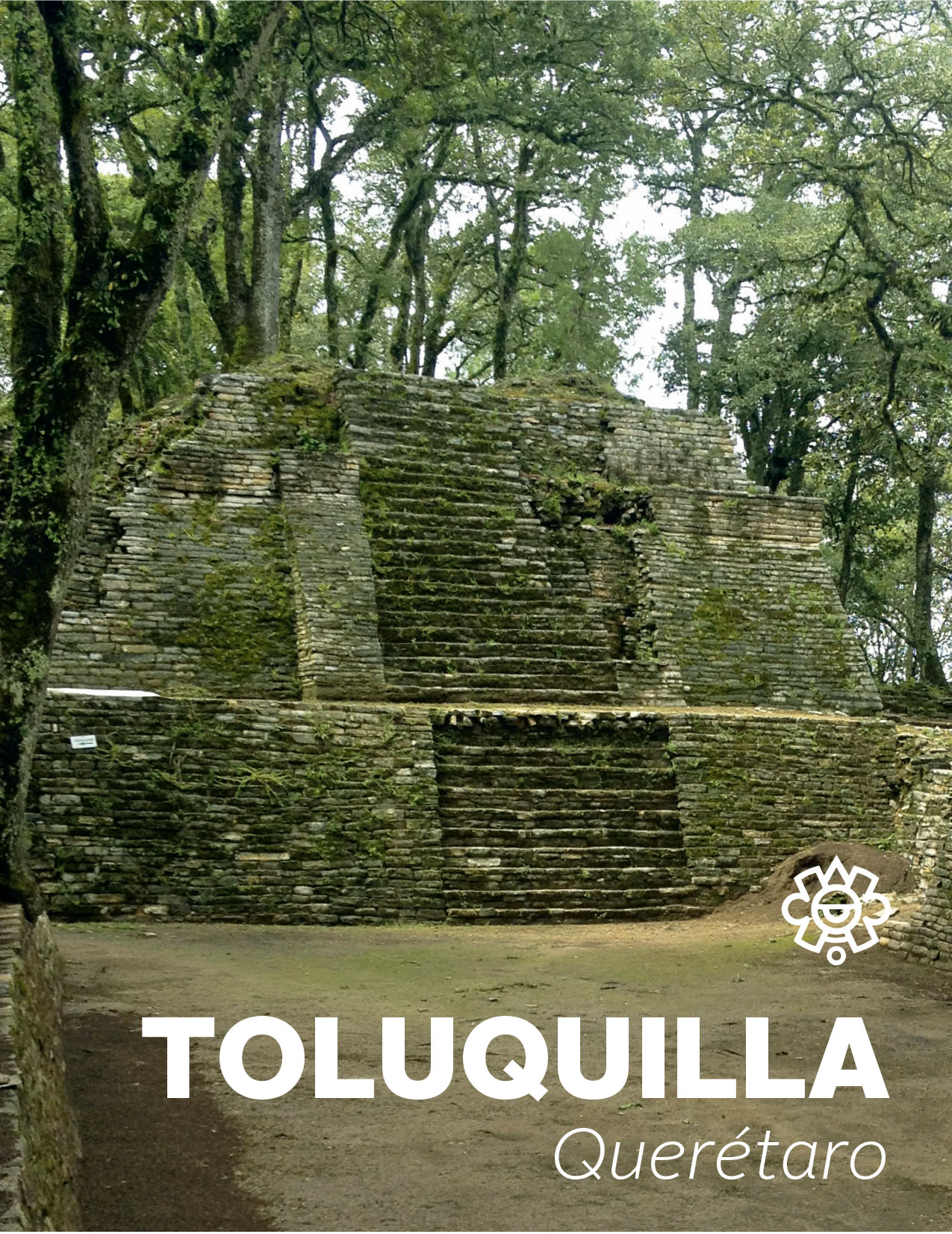

Situated south of the Sierra Gorda, this city was inhabited from 400 AD until shortly before the Conquest. Miners and mineral workers, influenced by different cultures, left impressive constructions in the area.

About the site

Toluquilla sits on a hill almost completely surrounded by ravines, which endows it with a strategic position to control the movement of people. This site’s importance is also largely owed to the mineral resources which are found nearby.

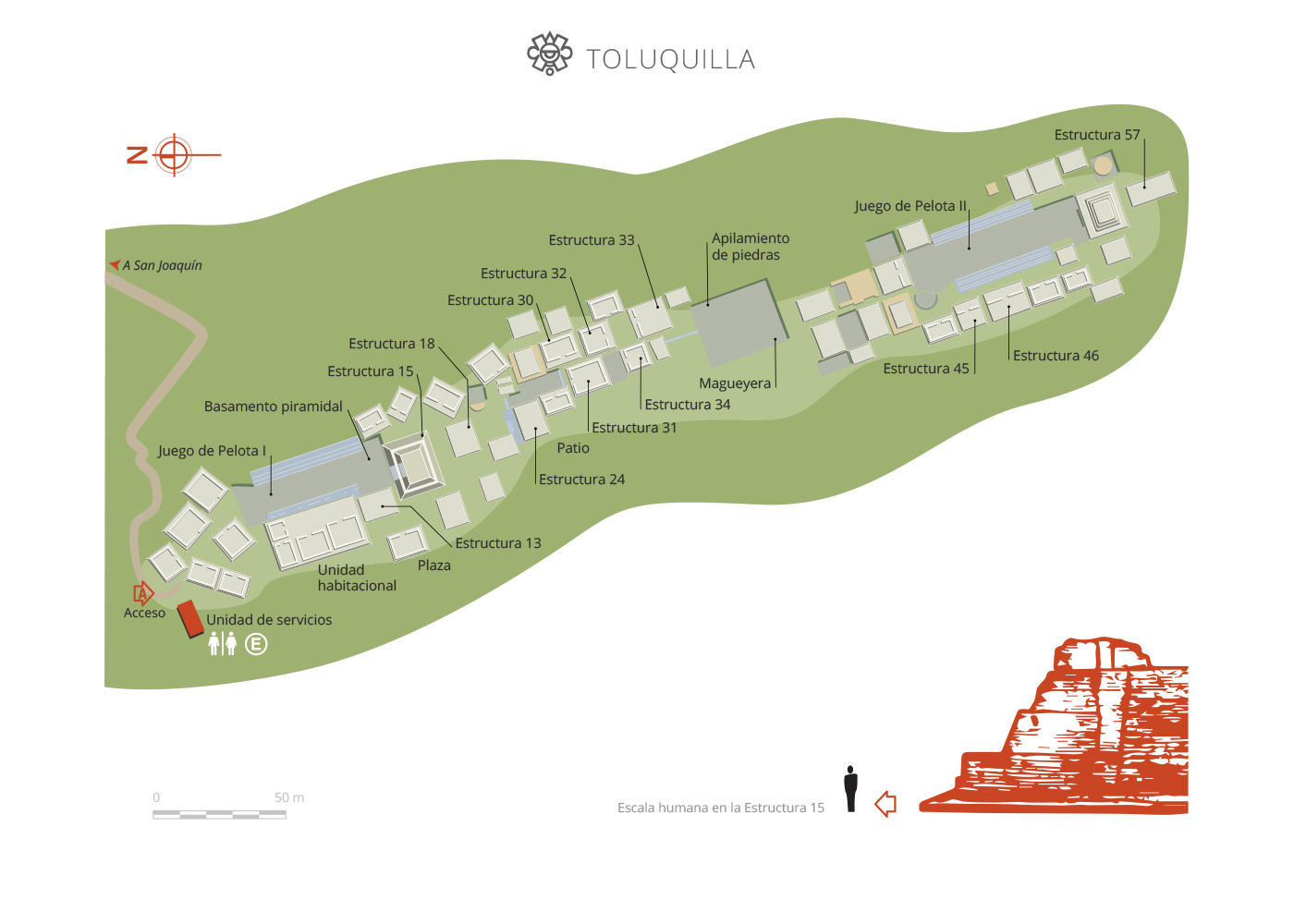

The upper section was shaped by excavating and infill to form flat areas at different levels. A medium-sized town was built on these terraces, with the buildings followed the north-south axis of the hill. Most of them were located on the summit: rooms, squares and temples distributed around four ballcourts. Terraces were formed to the south and the west of the hill, for the construction of houses.

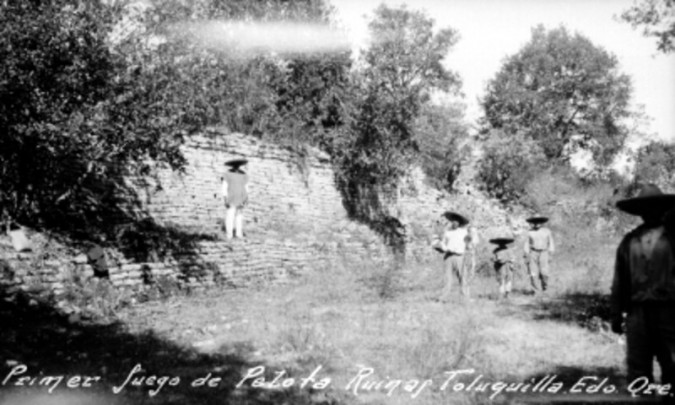

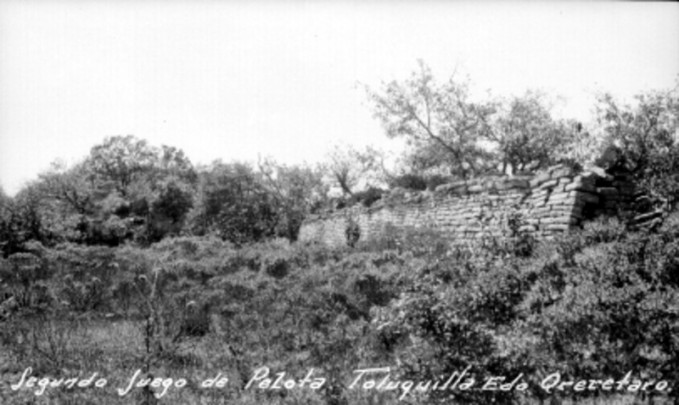

The first reference to the site is found in an 1838 issue of the newspaper "El Sol de México." However, it was between 1870 and 1880 that painters, travelers and, above all, mining engineers reported its existence more extensively. The majority of visitors marveled at what they saw and, given that they were not specialists, they compared the structures with those of Ancient Greece or Rome. They even spoke of walled fortresses, small forts and watchtowers.

The emergence of the discipline of archeology in the twentieth century led to a visit to Toluquilla. In 1931, the first archeologist arrived, Eduardo Noguera, who soon showed the military character attributed by former engineers to be false. He concluded that the site was related to Teotihuacan and Tula, and was also an intermediate point between the Gulf cultures and those from the center of Mexico.

As part of the newly created INAH Center in Querétaro, the archeologist Margarita Velasco worked in Toluquilla over two periods: first, for four months from 1987 and 1988, and later, in 2010. This specialist is responsible for the interpretation of the word Toluquilla, a hybrid term from the Náhuatl ‘toloa’, a verb which describes the the action of crouching and the Spanish suffix ‘illa’ (to make something small or endeared). Furthermore, according to the archeologist, Las Ranas is the largest site in the region, while Toluquilla is a secondary and incomplete site.

From 1996 until the present day, the INAH has maintained an ongoing research project at Toluquilla, under the responsibility of the archeologist Elizabeth Mejía Perez Campos. This has made it possible not only to obtain a large quantity of materials, but also to carry out radio carbon dating and DNA analysis. Today it is known that this town of 200 monuments (the largest in the state of Querétaro) specialized in the knowledge of, search for and exploitation of minerals. The settlers began by digging small holes and, over the years, excavated underground mines with winding tunnels that followed the mineral veins, as well as underground passages and some vertical shafts. Two red pigment minerals stand out: red ochre (iron oxide) and, above all, cinnabar (mercury sulphide). The latter was used extensively by the Olmecs, the Maya and the Teotihuacanos to cover the bodies of leaders in preparation for burial. It has been confirmed that cinnabar combined with oxygen was also used to paint the outer walls and murals inside living quarters, as well as to cover pots and other objects placed with the dead.

Toluquilla is very well preserved. Even before the archeological excavations, it was possible to explore its streets and alleys and pass through its doorways. The visit currently covers the entrance plaza, the first ballgame court, a residential complex, the Magueyera area and the second ballgame court. After this point, the site is overgrown and covered by five centuries’ worth of collapse. Altogether, around 40 percent of the ancient town has been explored.

The upper section was shaped by excavating and infill to form flat areas at different levels. A medium-sized town was built on these terraces, with the buildings followed the north-south axis of the hill. Most of them were located on the summit: rooms, squares and temples distributed around four ballcourts. Terraces were formed to the south and the west of the hill, for the construction of houses.

The first reference to the site is found in an 1838 issue of the newspaper "El Sol de México." However, it was between 1870 and 1880 that painters, travelers and, above all, mining engineers reported its existence more extensively. The majority of visitors marveled at what they saw and, given that they were not specialists, they compared the structures with those of Ancient Greece or Rome. They even spoke of walled fortresses, small forts and watchtowers.

The emergence of the discipline of archeology in the twentieth century led to a visit to Toluquilla. In 1931, the first archeologist arrived, Eduardo Noguera, who soon showed the military character attributed by former engineers to be false. He concluded that the site was related to Teotihuacan and Tula, and was also an intermediate point between the Gulf cultures and those from the center of Mexico.

As part of the newly created INAH Center in Querétaro, the archeologist Margarita Velasco worked in Toluquilla over two periods: first, for four months from 1987 and 1988, and later, in 2010. This specialist is responsible for the interpretation of the word Toluquilla, a hybrid term from the Náhuatl ‘toloa’, a verb which describes the the action of crouching and the Spanish suffix ‘illa’ (to make something small or endeared). Furthermore, according to the archeologist, Las Ranas is the largest site in the region, while Toluquilla is a secondary and incomplete site.

From 1996 until the present day, the INAH has maintained an ongoing research project at Toluquilla, under the responsibility of the archeologist Elizabeth Mejía Perez Campos. This has made it possible not only to obtain a large quantity of materials, but also to carry out radio carbon dating and DNA analysis. Today it is known that this town of 200 monuments (the largest in the state of Querétaro) specialized in the knowledge of, search for and exploitation of minerals. The settlers began by digging small holes and, over the years, excavated underground mines with winding tunnels that followed the mineral veins, as well as underground passages and some vertical shafts. Two red pigment minerals stand out: red ochre (iron oxide) and, above all, cinnabar (mercury sulphide). The latter was used extensively by the Olmecs, the Maya and the Teotihuacanos to cover the bodies of leaders in preparation for burial. It has been confirmed that cinnabar combined with oxygen was also used to paint the outer walls and murals inside living quarters, as well as to cover pots and other objects placed with the dead.

Toluquilla is very well preserved. Even before the archeological excavations, it was possible to explore its streets and alleys and pass through its doorways. The visit currently covers the entrance plaza, the first ballgame court, a residential complex, the Magueyera area and the second ballgame court. After this point, the site is overgrown and covered by five centuries’ worth of collapse. Altogether, around 40 percent of the ancient town has been explored.

Map

Did you know...

- The structures of the area known as the Magueyera were dismantled to plant maguey in their place.

- The inhabitants of Toluquilla sold cinnabar and red ocher in exchange for obsidian and seashells.

- The inhabitants' dedication to mining reveals their deep knowledge of the region in identifying locations for mineral extraction.

An expert point of view

Elizabeth Mejía Pérez Campos

Centro INAH Querétaro

-

+52 (442) 245 5204

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

VISITA VIRTUAL

Directory

Administrador de Zonas Arqueológicas del Centro INAH Querétaro

Armando Bahena Quintana

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (442) 212 2036, ext. 308013