Teotihuacan

The place of the gods

The great Mesoamerican city was at the heart of politics, the economy, trade, religion and culture. Its influence reached such distant places as Tikal. The city of Teotihuacan was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987, owing to the outstanding value of its monumental building complexes, mural paintings and living areas.

World heritage since 1987

About the site

This was the largest city in ancient Mexico. It had a population of approximately 100,000 inhabitants at its height (350-450 AD) and has left us extraordinary monuments like the enormous pyramids, as well as its outstanding urban layout (it was the first geometrically designed city in this hemisphere), and its superb mural paintings. It has been on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1987.

As capital of one of the first organized states, it maintained trade and political relations which stretched across great distances: the arid north of Mesoamerica (now Zacatecas), the Yucatan peninsula and the high Mayan lands of Petén (Campeche and Guatemala). It had a complex and hierarchical society, in which the priest class occupied the apex, followed by the warrior nobility. There followed the orders of artists and artisans (some living in districts for foreigners, such as the Zapotecs from the present-day state of Oaxaca), builders, miners and a vast number of farmers.

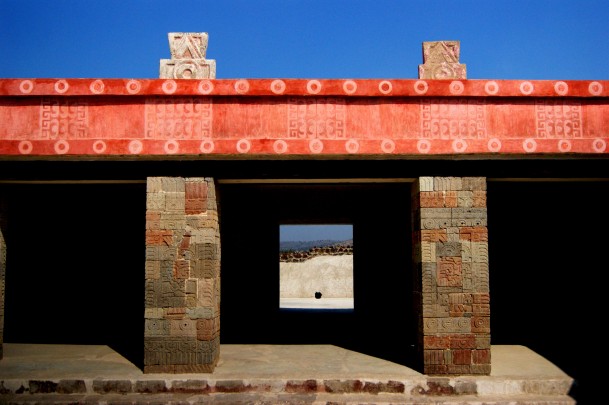

The community first emerged three centuries before the current era, established by villagers from the south of the five lakes in the Basin of Mexico. One characteristic of its architecture was the combination of “talud” (a sloping wall) and “tablero” (a vertical wall, frequently decorated with painted designs). By the third century AD, they had built the great Pyramid of the Sun, the beautiful Pyramid of the Moon and the Avenue of the Dead: their level of organization was already capable of this and more. The city occupied almost 8 square miles.

The city's trade routes soon reached the valleys that surround Monte Albán, Cholula and Matacapan (the latter in present-day Veracruz), as well as Kaminaljuyú and Tikal (both in what is now Guatemala), where the influence of Teotihuacan was made felt in different spheres such as the production of pottery and architecture. Cotton, precious feathers, fine blankets, sea and snail shell jewelry, chalchihuites (jade) and many fruits and vegetables arrived to the city from a multitude of markets, including very distant ones. Its apogee was reached in the fourth and fifth centuries AD.

However, violence erupted in the city in the mid-sixth century AD. Its central area was severely damaged, apparently by sectors of the population itself. The great city, sadly diminished, conserved a preeminent role in the region, but had to share it with others. Decline followed. In the thirteenth century, groups of people who spoke the Uto-Aztec language arrived from the north. As they passed through, they found it abandoned, surrounded by only a few hamlets. Its majestic, half-ruined constructions led them to call it admiringly in their language “place of the gods" or “place of deification”: Teotihuacan. Nobody knows what its inhabitants called it.

We do know that they worshipped Tlaloc for rain and agriculture, Huehueteotl for fire, Chalchiuhtlicue for running water, Quetzalcoatl for creative ability and the morning star, Quetzalpapalotl apparently for war and Xipe Totec for corn. They worshopped them all with names that have not survived, different to the Nahua names that prevailed. They believed that the dead lived on, and buried them as if for a journey, with offerings and formal attire. They thought they would last forever. However, these people, their city and their state only lasted from 50 to 650 AD.

In 1675, the colonial-period scholar Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora explored the square-based building at the foot of the staircase that climbs the Pyramid of the Moon. In the 1880s and in 1905, the anthropologist and archeologist Leopoldo Batres performed excavations and reconstructions near the Pyramid of the Moon and the Pyramid of the Sun on the instructions of President Porfirio Díaz. He also founded the first site museum. Three new projects of investigation, excavation and preservation (the largest in Mexico’s archeological history until then) were then performed in 1962-64 by the INAH. Others took place in 1980-82 and 1992-94. This interdisciplinary task continues.

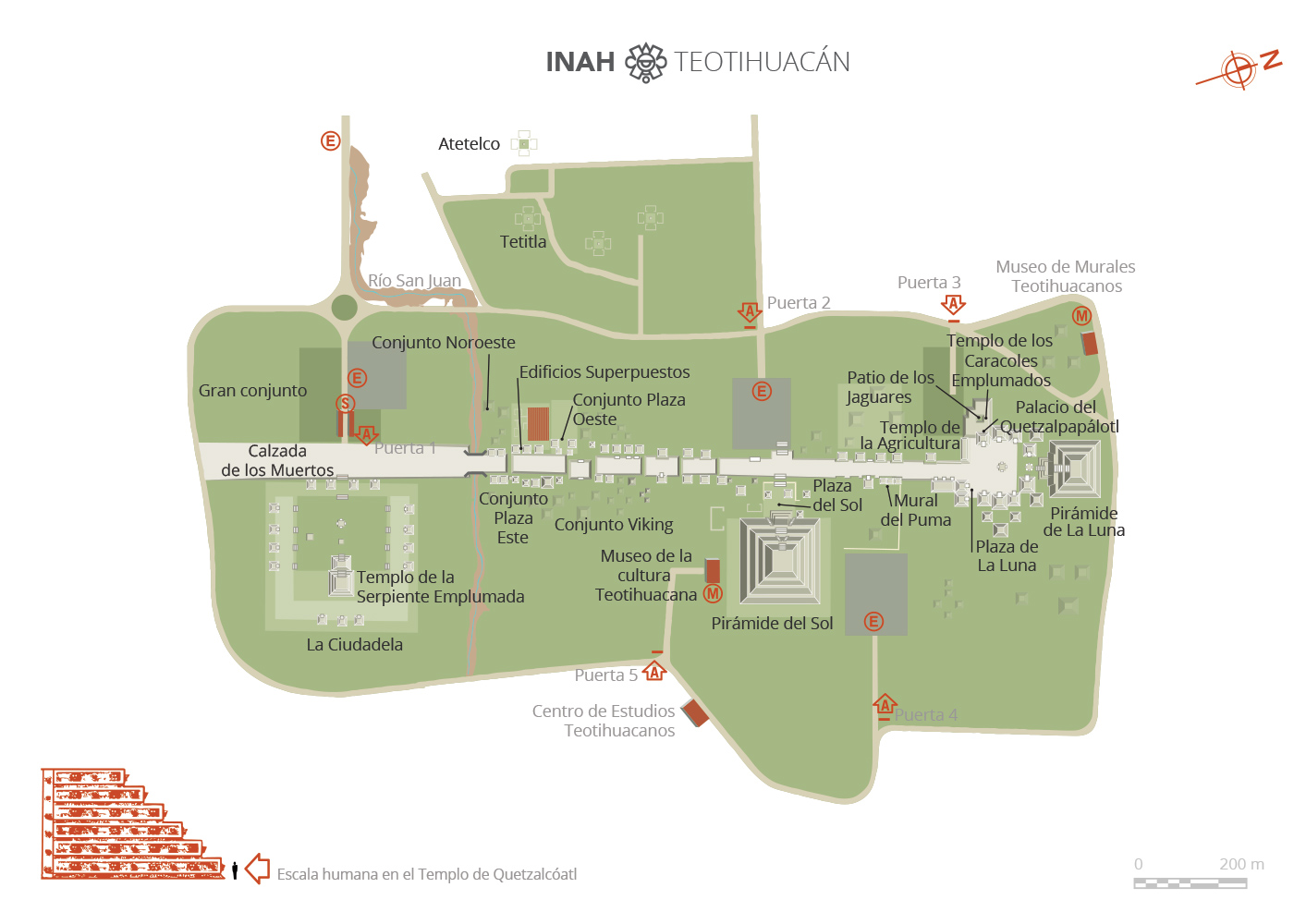

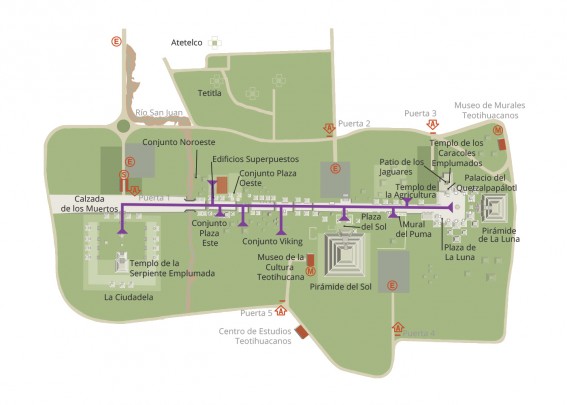

The archeological zone open to visitors covers 652 acres, within which the following main groups of structures and monuments can be found: the Citadel and the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl and three apartment areas with noteworthy mural paintings (Tetitla, Atetelco and Tepantitla).

Two site museums round off the visit and guide our learning and curiosity: the Museum of Teotihuacan Culture and the Beatriz de la Fuente Museum of Teotihuacan Murals, in addition to which there is a temporary exhibition hall in the so-called “Former Museum.” Archeological pieces can also be admired in the Sculpture Garden. It is also well worth visiting the botanical garden adjacent to the Museum of Teotihuacan Murals.

As capital of one of the first organized states, it maintained trade and political relations which stretched across great distances: the arid north of Mesoamerica (now Zacatecas), the Yucatan peninsula and the high Mayan lands of Petén (Campeche and Guatemala). It had a complex and hierarchical society, in which the priest class occupied the apex, followed by the warrior nobility. There followed the orders of artists and artisans (some living in districts for foreigners, such as the Zapotecs from the present-day state of Oaxaca), builders, miners and a vast number of farmers.

The community first emerged three centuries before the current era, established by villagers from the south of the five lakes in the Basin of Mexico. One characteristic of its architecture was the combination of “talud” (a sloping wall) and “tablero” (a vertical wall, frequently decorated with painted designs). By the third century AD, they had built the great Pyramid of the Sun, the beautiful Pyramid of the Moon and the Avenue of the Dead: their level of organization was already capable of this and more. The city occupied almost 8 square miles.

The city's trade routes soon reached the valleys that surround Monte Albán, Cholula and Matacapan (the latter in present-day Veracruz), as well as Kaminaljuyú and Tikal (both in what is now Guatemala), where the influence of Teotihuacan was made felt in different spheres such as the production of pottery and architecture. Cotton, precious feathers, fine blankets, sea and snail shell jewelry, chalchihuites (jade) and many fruits and vegetables arrived to the city from a multitude of markets, including very distant ones. Its apogee was reached in the fourth and fifth centuries AD.

However, violence erupted in the city in the mid-sixth century AD. Its central area was severely damaged, apparently by sectors of the population itself. The great city, sadly diminished, conserved a preeminent role in the region, but had to share it with others. Decline followed. In the thirteenth century, groups of people who spoke the Uto-Aztec language arrived from the north. As they passed through, they found it abandoned, surrounded by only a few hamlets. Its majestic, half-ruined constructions led them to call it admiringly in their language “place of the gods" or “place of deification”: Teotihuacan. Nobody knows what its inhabitants called it.

We do know that they worshipped Tlaloc for rain and agriculture, Huehueteotl for fire, Chalchiuhtlicue for running water, Quetzalcoatl for creative ability and the morning star, Quetzalpapalotl apparently for war and Xipe Totec for corn. They worshopped them all with names that have not survived, different to the Nahua names that prevailed. They believed that the dead lived on, and buried them as if for a journey, with offerings and formal attire. They thought they would last forever. However, these people, their city and their state only lasted from 50 to 650 AD.

In 1675, the colonial-period scholar Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora explored the square-based building at the foot of the staircase that climbs the Pyramid of the Moon. In the 1880s and in 1905, the anthropologist and archeologist Leopoldo Batres performed excavations and reconstructions near the Pyramid of the Moon and the Pyramid of the Sun on the instructions of President Porfirio Díaz. He also founded the first site museum. Three new projects of investigation, excavation and preservation (the largest in Mexico’s archeological history until then) were then performed in 1962-64 by the INAH. Others took place in 1980-82 and 1992-94. This interdisciplinary task continues.

The archeological zone open to visitors covers 652 acres, within which the following main groups of structures and monuments can be found: the Citadel and the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl and three apartment areas with noteworthy mural paintings (Tetitla, Atetelco and Tepantitla).

Two site museums round off the visit and guide our learning and curiosity: the Museum of Teotihuacan Culture and the Beatriz de la Fuente Museum of Teotihuacan Murals, in addition to which there is a temporary exhibition hall in the so-called “Former Museum.” Archeological pieces can also be admired in the Sculpture Garden. It is also well worth visiting the botanical garden adjacent to the Museum of Teotihuacan Murals.

150 a.C. - 800

Preclásico Tardío a Clásico Tardío

Clásico Temprano

300 - 400

Clásico Temprano

Map

Did you know...

- The Mexica called Teotihuacan’s main road Miccaotli (“Avenue of the Dead”), as they discovered the city when it had already been abandoned and believed that its platforms were tombs.

- An ancient tunnel was discovered below the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent in 2003. Archeologists have been excavating it since then. The tunnel predates the construction of the Citadel and its structures, and was created in approximately the first century BC. It is 112 yards long and found 17 yards below the surface. More than 1,000 tons of earth and stone had to be extracted to open it up. It was shut off 1,800 years ago with 18 successive walls of stone and mud. It ends in three chambers which symbolize the pre-Hispanic underworld. Valuable sculptures, items in green stone, many beads of these materials and others, large sea snail shells from the Gulf and the Caribbean, fine pottery statuettes and numerous other objects have been recovered from this tunnel.

- A valuable sculpture of Huehueteotl (as the Mexica called the deity, although the name given by the inhabitants from Teotihuacan is unknown) was found during excavations performed in September 2012 at the top of the Pyramid of the Sun, as well as two large stelae made of smooth green stone.

An expert point of view

Investigation and preservation of Structure A, Plaza of the Pyramid of the Moon, Teotihuacan

Verónica Ortega Cabrera

Zona Arqueológica de Teotihuacan

Practical information

Monday to Sunday from 09:00 to 16:00 hrs.

$100.00 pesos

Carretera Federal 132 Ecatepec-Pirámides km. 22 + 600, Municipio de Teotihuacan, C.P. 55800

Estado de México, México.

Estado de México, México.

From Mexico City, take Federal Highway 85D for Pachuca, and after a few kilometers take the exit that leads towards the archeological zone.

From Mexico City, take Federal Highway 132D Ecatepec-Pirámides.

From Mexico City, take Federal Highway 132D Ecatepec-Pirámides.

Services

Directory

Director de la Zona Arqueológica

Rogelio Rivero Chong

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (594) 956 0276, exts. 198500 y 198501