Bonampak

Painted walls

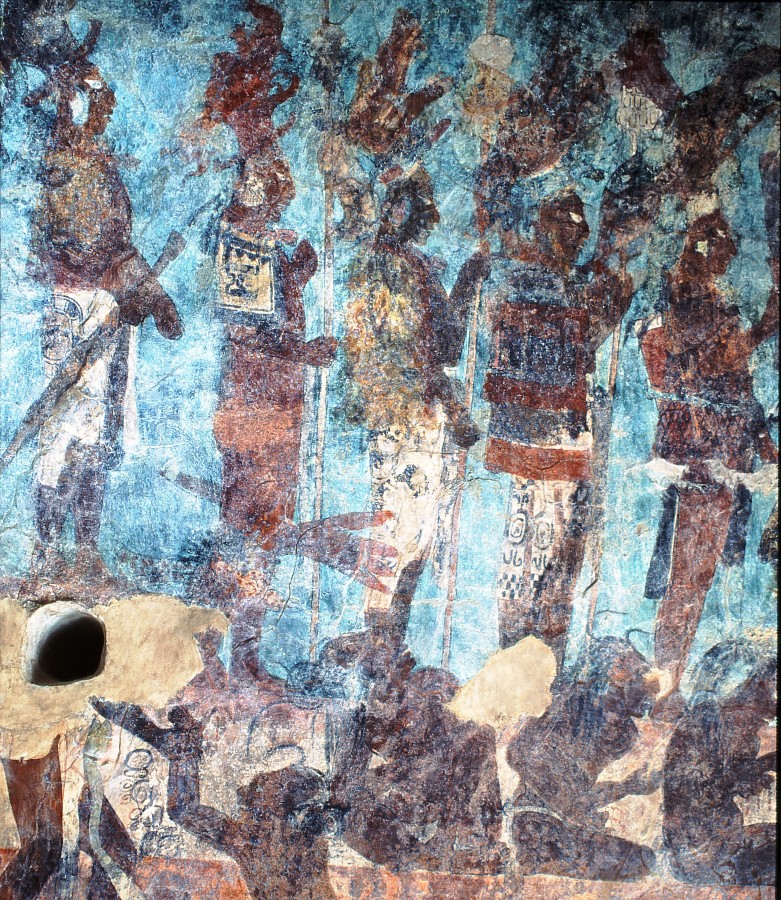

In the heart of the Lacandon jungle, Bonampak is famous for its extraordinary murals, which show scenes of war, paying tribute and the capture of prisoners for sacrifice.

About the site

This little-known Mayan city is 1800 years old, and it reached its apogee between 600 and 800 AD. Its first few centuries were spent under the dominion of Piedras Negras and later Yaxchilán. The political, administrative and religious center of the city was never very large, but it was more spread out than other Mayan cities in the Usumacinta basin, owing to the capacity for agricultural production of its surrounding valley, which produced cacao as well basic foods. The city must have been segmented into several neighborhoods directed by members of the local aristocracy, who were responsible for collecting taxes for the governor.

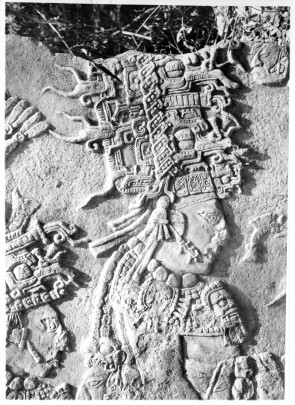

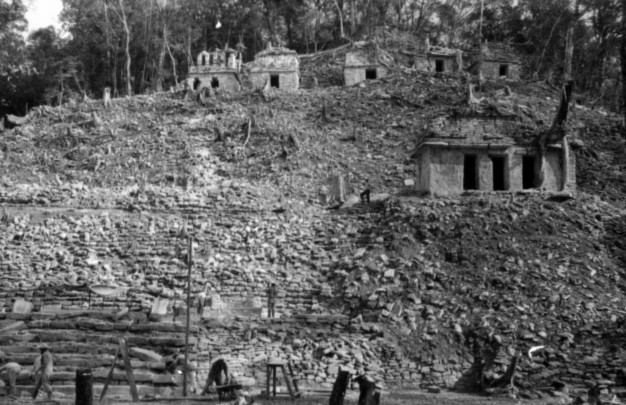

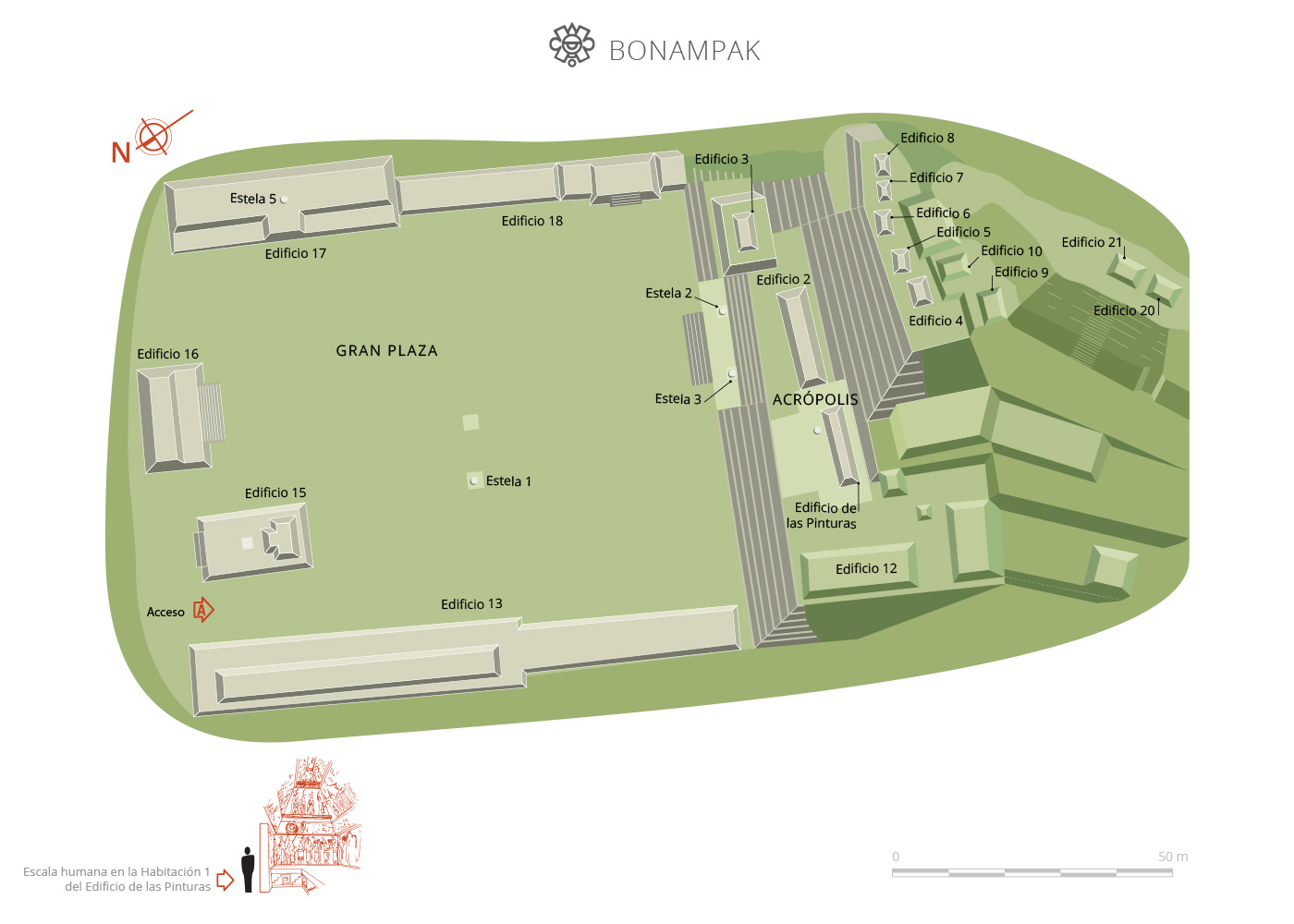

Bonampak has a central plaza surrounded by not very tall religious, administrative and residential buildings. A stela in the plaza and others on the steps of the Acropolis demonstrate very fine workmanship. To the south of the Great Plaza, the impressively large Acropolis has a stepped base and is 150 feet high. All buildings that have Mayan vaults in the city are in this area, distributed on two levels, which are reached by broad stairways. On the first level there are three buildings, and the one on the right is reminiscent of the magnificent Building 33 at Yaxchilán on account of its shape and size. The local Lacandon people were amazed when they discovered the three rooms inside the Building of the Paintings, which had been abandoned many centuries earlier, and when they guided foreign visitors there for the first time one day in 1946, they too were stunned. The three rooms were, and still are, profusely decorated with mural paintings, some of the best conserved and revealing of ancient Mexico.

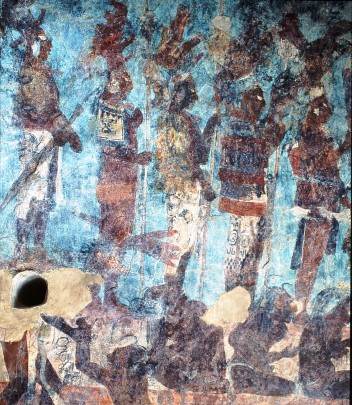

The artists Antonio Tejeda and Agustín Villagra made the first copies of the murals during the first three scientific expeditions to Bonampak by the Washington Carnegie Institution between 1946 and 1948. The task was hindered by the fact that the murals were hard to see as they were covered by a thick layer of carbonate salt deposits. The INAH restored the murals in 1984 after extensive and lengthy deliberation at national and international levels, to a large extent recovering their original bright colors.

New studies of the murals were carried out in the 1990s, one led by the Institute for Aesthetic Research of the National Autonomous University of Mexico which culminated in the publication of two volumes with complete photographs of the murals and another, led by Mary E. Miller of Yale University, which used photographs as the basis for a digital reconstruction of the murals. Since 2011 the INAH has begun a second restoration process, this time using modern methods, which enable us to see the room 3 murals in fine detail.

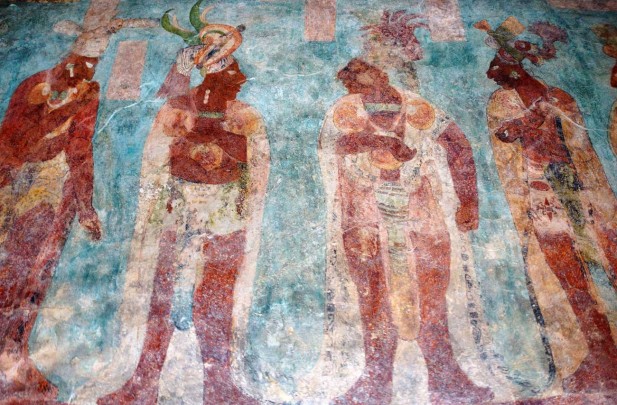

The Bonampak murals have recovered their vitality as a result of these processes. In the first room from left to right we observe a procession of priests and members of the nobility. The second features an important battle in which Chan Muwan II, the lord or "ajaw" of the city, defeated the previous governor with the support of Yaxchilán. The governor had attempted to maintain the neighboring city of Sak´ Tz´i´, and he was imprisoned with his captains in preparation for sacrifice. The final room shows a ceremony with dancers in resplendent dress, the family of the victorious lord and the lord himself practicing the self-sacrifice ritual of bleeding the tongue with obsidian knives.

Bonampak has a central plaza surrounded by not very tall religious, administrative and residential buildings. A stela in the plaza and others on the steps of the Acropolis demonstrate very fine workmanship. To the south of the Great Plaza, the impressively large Acropolis has a stepped base and is 150 feet high. All buildings that have Mayan vaults in the city are in this area, distributed on two levels, which are reached by broad stairways. On the first level there are three buildings, and the one on the right is reminiscent of the magnificent Building 33 at Yaxchilán on account of its shape and size. The local Lacandon people were amazed when they discovered the three rooms inside the Building of the Paintings, which had been abandoned many centuries earlier, and when they guided foreign visitors there for the first time one day in 1946, they too were stunned. The three rooms were, and still are, profusely decorated with mural paintings, some of the best conserved and revealing of ancient Mexico.

The artists Antonio Tejeda and Agustín Villagra made the first copies of the murals during the first three scientific expeditions to Bonampak by the Washington Carnegie Institution between 1946 and 1948. The task was hindered by the fact that the murals were hard to see as they were covered by a thick layer of carbonate salt deposits. The INAH restored the murals in 1984 after extensive and lengthy deliberation at national and international levels, to a large extent recovering their original bright colors.

New studies of the murals were carried out in the 1990s, one led by the Institute for Aesthetic Research of the National Autonomous University of Mexico which culminated in the publication of two volumes with complete photographs of the murals and another, led by Mary E. Miller of Yale University, which used photographs as the basis for a digital reconstruction of the murals. Since 2011 the INAH has begun a second restoration process, this time using modern methods, which enable us to see the room 3 murals in fine detail.

The Bonampak murals have recovered their vitality as a result of these processes. In the first room from left to right we observe a procession of priests and members of the nobility. The second features an important battle in which Chan Muwan II, the lord or "ajaw" of the city, defeated the previous governor with the support of Yaxchilán. The governor had attempted to maintain the neighboring city of Sak´ Tz´i´, and he was imprisoned with his captains in preparation for sacrifice. The final room shows a ceremony with dancers in resplendent dress, the family of the victorious lord and the lord himself practicing the self-sacrifice ritual of bleeding the tongue with obsidian knives.

Map

Did you know...

- Bonampak is the only archeological site in the Mayan world that has murals with such a high degree of conservation.

- Remains of the same pictorial style are preserved in a building at Yaxchilán and another two in the small dependent towns of La Pasadita and El Tecolote, both in Guatemala. This indicates that this visual tradition was exported to Bonampak from Yaxchilán.

- The murals are found inside Building 1 of Bonampak and occupy the entire walls of the three rooms. They cover an area of 1,205 square feet, over which 108 hieroglyphic clauses and 270 characters are distributed.

- Although several of the characters appear multiple times in the murals of the three rooms, all the individuals depicted there present different clothes and decorations, which speaks of the wealth of clothing worn by the Mayan nobility.

- At the beginning of the 20th century, Lacandón Kin, father of Kin Obregón, discovered the ruins that in 1946 would be baptized as Bonampak, or "painted walls."

- It was revealed to the world by Charles Frey in 1946, who arrived in February of that year guided by his friend José Pepe Chambor, and accompanied by the millionaire John Bourne and several gum farmers.

- Giles Healey is credited with being the first Westerner to see the murals in the Building of the Paintings in June of the same year. However, it is probable that Frey had seen them and, to protect his Lacandon friends from the arrival of thousands of tourists, kept the discovery to himself.

An expert point of view

The images are a unique survival in Mesoamerica

Alejandro Tovalín

Centro INAH Chiapas

Practical information

Monday to Sunday from 8:00 to 16:30 hrs. Last entry 16:00.

$100.00 pesos

Se ubica en la selva Lacandona de Chiapas, en el valle del río Lacanjá

There are two ways to get to Bonampak: one is by air, with small planes that depart from Palenque, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Ocosingo, Comitán or Tenosique Tabasco.

Another route is highway 199 that goes from Palenque - Chancalá - Corozal Border, as far as the San Javier exit at km 97; continue on the road towards Lacanhá and the archeological zone is 4 km further on.

Another route is highway 199 that goes from Palenque - Chancalá - Corozal Border, as far as the San Javier exit at km 97; continue on the road towards Lacanhá and the archeological zone is 4 km further on.

-

+52 (916) 345 2705

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Directory

Subdirectora de la Zona Arqueológica

Keiko Teranishi Castillo

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (916) 345 2721