Dzibilchaltún

Writing on the flat stones

The Temple of the Seven Dolls attracts hundreds of visitors at the spring and fall equinoxes, when the sun shines through the building and illuminates the doorway. There are numerous admirable stelae, beautifully carved, and an open cenote (underground pool) with crystal clear waters.

About the site

The Dzibilchaltun archaeological site is situated seven and a half miles to the north of the city of Merida, in the state of Yucatan. The area of the site approaches eight square miles and it includes the remains of various pre-Hispanic settlements of different periods. The Central Plaza as it is found today dates from a period of occupation in the Late Classic period, between 850 and 1100 AD. However, much older buildings that were buried by the infill of more recent buildings were discovered during the survey of the structures surrounding the Xlacah Cenote, and these are from the Middle Preclassic period, probably dating around 600 BC. Despite the fact that the center of the site which we now know as Dzibilchaltun was occupied from early times, there was a much larger and more influential city called Komchen a few miles to the northwest. Komchen dominated the northwest region of the Yucatan peninsula in the final stage of the Postclassic period and for much of the Classic, probably owing to its extraction and trading of salt, an important resource which was exchanged for jadeite from the Motagua River region on the present-day border between Guatemala and Honduras, as well as for ceramics from the central Petén and the west of Chiapas.

Dzibilchaltun had taken over control of the northwest region of the peninsula from Komchen by the end of the Classic. A large population, possibly close to 25,000, lived in the vicinity of the ceremonial city center organized around three large plazas and five long avenues paved with limestone mortar, which is why they are known in Maya as sacbeob, or sacbe in the singular, literally meaning "white roads." It is likely that during the Late Classic (around 800 AD), the name of the site might have referred to "the five that spring from the mouth of the celestial serpent," which alludes to the divine tetrarchies which inhabit the various regions of the world according to pre-Hispanic thought, such as the four k’awiles, bacabes or pahuatunes which live in the four points of the sky. In this case it could refer to a group of five deities associated with the Milky Way, which is sometimes described as a heavenly snake that dwells in the night sky. The fact that the urban plan of the Late Classic settlement includes a system of paved roads whose orientation fits with the four points of the compass on a symmetrical pattern which emerges from two central plazas suggests that the name of the city was derived from its shape.

The investigation of Dzibilchaltun fell into two important periods. The first was led by Edward Wyllys Andrews IV, a US archaeologist, who, before the Second World War, directed the compilation of one of the first maps of Mesoamerica in conjunction with George Sturt of the National Geographic Society. Then at the end of the 1950s, Andrews returned with a team of researchers from the Middle American Research Institute of the University of Tulane, in addition to staff from the National Geographic Society working under the supervision of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). Over the period of a decade of work in the area, this team of researchers carried out underwater archeology in the Xlacah Cenote and restored the Templo de las Siete Muñecas ("Temple of the Seven Dolls") as well as mapping an area of over 12 square miles. The second period of exploration has been directed by Rubén Maldonado Cárdenas, a Mexican archeologist who has dedicated a substantial part of his professional career to Dzibilchaltun since the late 1990s. Practically all of the structures around the Central Plaza were excavated and consolidated by his team over a twenty-year period. Of particular note was the burial of Kalomte’ Uk’uw Ux Chan Chaak, an important Late Classic period monarch.

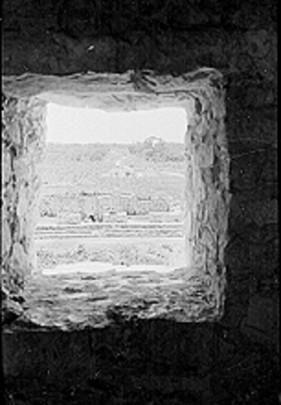

The Temple of the Sun or House of the Seven Dolls, named after the seven ceramic human figures found during the excavation of the site in the 1950s, is a square-based pyramid comprising two bodies, of medium height and with broad and well-worked steps on the four sides culminating in an elegant roofed temple with doors facing east and west. At dawn on the spring and autumn equinoxes of 21 March and 21 September respectively, a powerful beam of sunlight crosses both doors of the shrine at the top for an instant. It was believed that this was a sign sent by Kinich Ahau, the sun god, to indicate the time for sowing or harvesting. The Mayan astronomers and builders took great care to ensure that this marvel worked.

Of the city’s stone-surfaced roads connecting the center to the periphery, there is a long road connecting the city center to other complexes in the surrounding area, especially the shrine of the great stele, with its great stairway, the excavated residential complex of Group 4, and the pyramidal structures which line its route to the crystal clear waters of the Xlacah Cenote, which means “old town” in Maya. The cenote, which measures 130 feet wide by 330 feet long, with a depth of 130 feet, is one of the largest of the peninsula and archeological finds, principally ceramic vessels, have been discovered inside it. Before reaching the cenote the route takes visitors through a notable open chapel built by the Franciscans in the sixteenth century, soon after the Spanish conquest. The final essential stop on the itinerary is a visit to the rich and well laid-out Museum of the Mayan People.

Dzibilchaltun had taken over control of the northwest region of the peninsula from Komchen by the end of the Classic. A large population, possibly close to 25,000, lived in the vicinity of the ceremonial city center organized around three large plazas and five long avenues paved with limestone mortar, which is why they are known in Maya as sacbeob, or sacbe in the singular, literally meaning "white roads." It is likely that during the Late Classic (around 800 AD), the name of the site might have referred to "the five that spring from the mouth of the celestial serpent," which alludes to the divine tetrarchies which inhabit the various regions of the world according to pre-Hispanic thought, such as the four k’awiles, bacabes or pahuatunes which live in the four points of the sky. In this case it could refer to a group of five deities associated with the Milky Way, which is sometimes described as a heavenly snake that dwells in the night sky. The fact that the urban plan of the Late Classic settlement includes a system of paved roads whose orientation fits with the four points of the compass on a symmetrical pattern which emerges from two central plazas suggests that the name of the city was derived from its shape.

The investigation of Dzibilchaltun fell into two important periods. The first was led by Edward Wyllys Andrews IV, a US archaeologist, who, before the Second World War, directed the compilation of one of the first maps of Mesoamerica in conjunction with George Sturt of the National Geographic Society. Then at the end of the 1950s, Andrews returned with a team of researchers from the Middle American Research Institute of the University of Tulane, in addition to staff from the National Geographic Society working under the supervision of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). Over the period of a decade of work in the area, this team of researchers carried out underwater archeology in the Xlacah Cenote and restored the Templo de las Siete Muñecas ("Temple of the Seven Dolls") as well as mapping an area of over 12 square miles. The second period of exploration has been directed by Rubén Maldonado Cárdenas, a Mexican archeologist who has dedicated a substantial part of his professional career to Dzibilchaltun since the late 1990s. Practically all of the structures around the Central Plaza were excavated and consolidated by his team over a twenty-year period. Of particular note was the burial of Kalomte’ Uk’uw Ux Chan Chaak, an important Late Classic period monarch.

The Temple of the Sun or House of the Seven Dolls, named after the seven ceramic human figures found during the excavation of the site in the 1950s, is a square-based pyramid comprising two bodies, of medium height and with broad and well-worked steps on the four sides culminating in an elegant roofed temple with doors facing east and west. At dawn on the spring and autumn equinoxes of 21 March and 21 September respectively, a powerful beam of sunlight crosses both doors of the shrine at the top for an instant. It was believed that this was a sign sent by Kinich Ahau, the sun god, to indicate the time for sowing or harvesting. The Mayan astronomers and builders took great care to ensure that this marvel worked.

Of the city’s stone-surfaced roads connecting the center to the periphery, there is a long road connecting the city center to other complexes in the surrounding area, especially the shrine of the great stele, with its great stairway, the excavated residential complex of Group 4, and the pyramidal structures which line its route to the crystal clear waters of the Xlacah Cenote, which means “old town” in Maya. The cenote, which measures 130 feet wide by 330 feet long, with a depth of 130 feet, is one of the largest of the peninsula and archeological finds, principally ceramic vessels, have been discovered inside it. Before reaching the cenote the route takes visitors through a notable open chapel built by the Franciscans in the sixteenth century, soon after the Spanish conquest. The final essential stop on the itinerary is a visit to the rich and well laid-out Museum of the Mayan People.

Map

Did you know...

- Stele 19 is considered a true masterpiece.

- Dzibilchaltun gathers in a single site a pre-Hispanic city, an eco-archeological park and the Museum of the Mayan People.

- The phenomenon of light and shade at the spring and autumn equinoxes was rediscovered around 1985 by the archeologist Víctor Segovia Pinto.

An expert point of view

Ilan Vit-Suzan

Zona Arqueológica de Dzibilchaltún

Practical information

Temporarily closed

Tuesday to Sunday from 08:00 to 17:00 hrs.

$95.00 pesos

Carretera a Chablekal km 6.5, Comisaría de Mérida, Zona Arqueológica de Dzibilchaltún, C.P. 97310 Mérida, Yucatán, México.

From the city of Mérida take Federal Highway no. 261 to Puerto Progreso and then the exit for the towns of Chablekal and Conkal. The turn off that leads to the archeological zone is found after the town of Dzibilchaltún.

Services

-

+52 (999) 944 4068

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

TWITTER

Directory

Responsable operativo de la Zona Arqueológica

Ilan Vit-Suzan

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (999) 922 0193