Cholula

Place of flight

This is the most important pre-Hispanic settlement of those explored so far in the state of Puebla, and one of the main sites in Mexico. Its attractions include the Great Pyramid and the plaza known as the “courtyard of altars.”

About the site

The archeological zone of Cholula lies in the Puebla-Tlaxcala Valley, in the southeast of the Central Mexican Plateau. It is bordered to the north, east and west by mountainous areas, while the south opens up to the extensive Mixtec regions. Several rivers and streams cross the valley as a result of snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada, which makes these lands of outstanding quality for agriculture. Chief among these is the Atoyac, an important tributary of the Balsas River.

The ancient settlement lies between the municipalities of San Andrés and San Pedro Cholula, 73 miles east of Mexico City and just 4 miles from the capital of Puebla via a direct expressway known as the Quetzalcóatl Route.

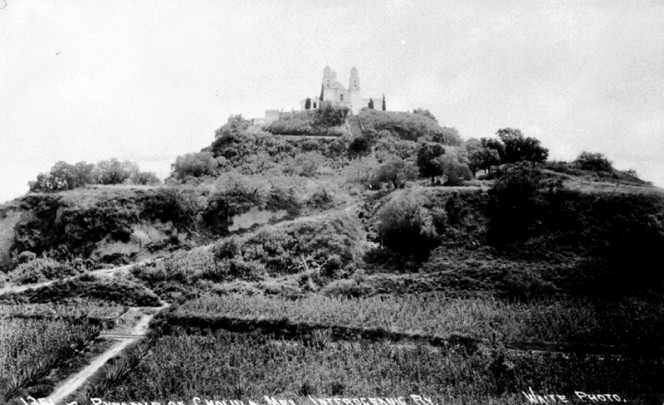

In November of 1519, when Hernán Cortés and his army entered the city then known as Cholollan, what is now the archeological zone open to the public was a site that had already been abandoned and destroyed eight centuries earlier. The total ruin of the complex gave it the appearance (which it still maintains today) of a small hill covered in trees, soil and weeds. Years later, Fray Toribio de Benavente (Motolinia), discovered that it was the ruins of an ancient teocalli and he described it as such in his History of the Indians of New Spain.

A number of famous scholars such as Alexander von Humbolt and Captain Guillermo Dupaix were interested in this monument and its historical importance. Early explorations were made by archeologists such as Leopoldo Batres, Manuel Gamio and Enrique Juan Palacios, but work formally began in 1931 under the guidance of the architect Ignacio Marquina. His system of exploration based on tunnels to detect substructures was a resounding success and remains an example of technique and tenacity to this day.

The space currently occupied by the archeological zone of Cholula is just a small part of what was once an important pre-Hispanic city, which rivaled places such as Teotihuacan, El Tajín, Monte Albán and Xochicalco. The first signs of occupation in the area date back more than a millennium before the current era, but it was clearly occupied by the sixth century BC, with a growing population on the edges of a now-vanished marsh. The site for the first temple was chosen above a spring in order for the building to be consecrated. This was due to the magical-religious associations of spring water in ancient indigenous conceptions.

By the second century BC, conditions were such that they allowed for the construction of a pyramid base of regular dimensions. This was the first Great Pyramid, which measures approximately 427 feet on each side at its base, with four sloping sections and a stairway on the west side. This structure was built at the same time as the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan.

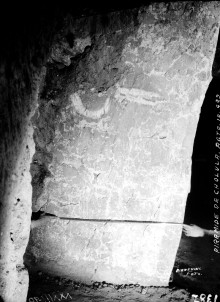

Unlike other Mesoamerican buildings, large blocks of compacted dirt (adobe) were used here. These were stuck together with mud to form an enormous core. Certain elements were added to this pyramid, such as a series of panels decorated with a mural painting depicting insects with heads similar to human skulls. These are called “los chapulines” (the crickets).

The city’s rapid expansion and its growing role as a religious sanctuary and economic center were perhaps the reasons for planning the construction of a larger base. This led to the raising of the second Great Pyramid, larger than that of the Moon in Teotihuacan. Its square base measures close to 558 feet per side and it is almost 148 feet tall. This pyramidal base echoed the original layout. The shape of each of its nine sloped sections is formed from steps. These are merely symbolic in some parts, and the staircase for use would have been on the west side. In addition, the corners of this pyramid are recessed, lending the whole a distinctive appearance. The building was also covered with a thick coat of stucco that was originally painted with bright colors and symbolic designs.

As with the earlier pyramid, other buildings with their own plinths, stairs and corridors were placed on top. There were so many that it has been said that the “hill” has seven pyramids on top of it. The ruins of ancient buildings have been found on the south side of the pyramid, all with the same characteristics. They have recessed panels and are decorated with diagonal bands painted in vivid colors with depictions of elements such as starfish and snails.

The facade of one of these buildings remains almost completely intact. It is approximately 213 feet long, with a variable height that measures six and a half feet on average. The wall is decorated with an image in very well-preserved colors. It shows a ceremony connected to drinking, depicting a large number of people most of whom are holding vessels large and small for drinking a whitish alcoholic beverage which is most likely pulque. The pictorial motif is presented in two sections. The lower section takes place on a long bench from which hangs a tapestry with extraordinary designs. This has been called the “mural of the drinkers” and it is one of the richest examples of pre-Hispanic mural painting. It dates to approximately the third century AD. At the time, there were several ethnic groups in the population, both from the coast and the rest of the central plateau. Its tianquiztli or market was one of the most famous in Mesoamerica.

A building was added on the west side of the pyramid that had several sections and a long staircase almost fifty feet tall. Its panels were decorated with a characteristic cross-hatching, as can be seen in the current reconstruction.

Once again, the idea of a bigger, taller temple and pyramid inspired the ruling theocracy and the devout people to embark on a truly titanic work. A still-larger pyramid was constructed over the second pyramid and all of its additions. This would be the true Great Pyramid, as it covered an area measuring more than 1,300 feet on each side. The average height of this monumental structure was almost 213 feet, without counting the height of the temple, which would have been very tall. These characteristics made the great teocalli (possibly dedicated to the god of water or rain) the biggest in the pre-Hispanic world. People from other towns called this sanctuary Tlachihualtepetl, which means “artificial hill” or “manmade hill”.

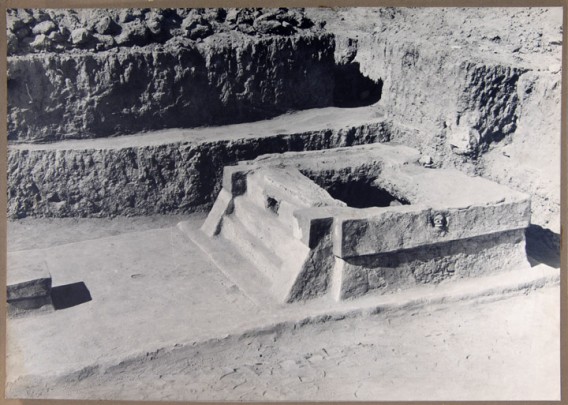

Large open spaces were created on each side of the great pyramid, bordered by elegantly decorated buildings. Such is the case of the southern plaza, which is known as the “courtyard of altars” owing to the altars and stelae found there, which are made of some type of metamorphic rock and decorated with scrolls that seem to be stylized bird feathers reminiscent of designs from the Gulf coast.

At the end of the eighth century, Mesoamerica experienced a profound change. Its greatest cities began to decline and some were abandoned. The holy city of Tlachihualtepetl suffered wars and calamities, and the crisis was accelerated by an eruption from the volcano of Popocatépetl. The great ceremonial center was destroyed, sacked and later abandoned. The buildings began to be covered by the dirt from the adobe as it crumbled. Little by little, grass and trees began to grow, until it all took on the appearance of a desolate hill. Many years later, some small buildings such as altars and tombs were constructed on the abandoned platforms, but these had no connection to the ancient sanctuary.

Not long after the disaster, the survivors (together with the invaders) built a new ceremonial center where the main square of the city of San Pedro Cholula now lies. This was a place that managed to regain its lost grandeur and splendor. It was there that the conqueror Hernán Cortés carried out one of the cruelest slaughters recorded in human history in order to intimidate the Tenochca.

The ancient settlement lies between the municipalities of San Andrés and San Pedro Cholula, 73 miles east of Mexico City and just 4 miles from the capital of Puebla via a direct expressway known as the Quetzalcóatl Route.

In November of 1519, when Hernán Cortés and his army entered the city then known as Cholollan, what is now the archeological zone open to the public was a site that had already been abandoned and destroyed eight centuries earlier. The total ruin of the complex gave it the appearance (which it still maintains today) of a small hill covered in trees, soil and weeds. Years later, Fray Toribio de Benavente (Motolinia), discovered that it was the ruins of an ancient teocalli and he described it as such in his History of the Indians of New Spain.

A number of famous scholars such as Alexander von Humbolt and Captain Guillermo Dupaix were interested in this monument and its historical importance. Early explorations were made by archeologists such as Leopoldo Batres, Manuel Gamio and Enrique Juan Palacios, but work formally began in 1931 under the guidance of the architect Ignacio Marquina. His system of exploration based on tunnels to detect substructures was a resounding success and remains an example of technique and tenacity to this day.

The space currently occupied by the archeological zone of Cholula is just a small part of what was once an important pre-Hispanic city, which rivaled places such as Teotihuacan, El Tajín, Monte Albán and Xochicalco. The first signs of occupation in the area date back more than a millennium before the current era, but it was clearly occupied by the sixth century BC, with a growing population on the edges of a now-vanished marsh. The site for the first temple was chosen above a spring in order for the building to be consecrated. This was due to the magical-religious associations of spring water in ancient indigenous conceptions.

By the second century BC, conditions were such that they allowed for the construction of a pyramid base of regular dimensions. This was the first Great Pyramid, which measures approximately 427 feet on each side at its base, with four sloping sections and a stairway on the west side. This structure was built at the same time as the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan.

Unlike other Mesoamerican buildings, large blocks of compacted dirt (adobe) were used here. These were stuck together with mud to form an enormous core. Certain elements were added to this pyramid, such as a series of panels decorated with a mural painting depicting insects with heads similar to human skulls. These are called “los chapulines” (the crickets).

The city’s rapid expansion and its growing role as a religious sanctuary and economic center were perhaps the reasons for planning the construction of a larger base. This led to the raising of the second Great Pyramid, larger than that of the Moon in Teotihuacan. Its square base measures close to 558 feet per side and it is almost 148 feet tall. This pyramidal base echoed the original layout. The shape of each of its nine sloped sections is formed from steps. These are merely symbolic in some parts, and the staircase for use would have been on the west side. In addition, the corners of this pyramid are recessed, lending the whole a distinctive appearance. The building was also covered with a thick coat of stucco that was originally painted with bright colors and symbolic designs.

As with the earlier pyramid, other buildings with their own plinths, stairs and corridors were placed on top. There were so many that it has been said that the “hill” has seven pyramids on top of it. The ruins of ancient buildings have been found on the south side of the pyramid, all with the same characteristics. They have recessed panels and are decorated with diagonal bands painted in vivid colors with depictions of elements such as starfish and snails.

The facade of one of these buildings remains almost completely intact. It is approximately 213 feet long, with a variable height that measures six and a half feet on average. The wall is decorated with an image in very well-preserved colors. It shows a ceremony connected to drinking, depicting a large number of people most of whom are holding vessels large and small for drinking a whitish alcoholic beverage which is most likely pulque. The pictorial motif is presented in two sections. The lower section takes place on a long bench from which hangs a tapestry with extraordinary designs. This has been called the “mural of the drinkers” and it is one of the richest examples of pre-Hispanic mural painting. It dates to approximately the third century AD. At the time, there were several ethnic groups in the population, both from the coast and the rest of the central plateau. Its tianquiztli or market was one of the most famous in Mesoamerica.

A building was added on the west side of the pyramid that had several sections and a long staircase almost fifty feet tall. Its panels were decorated with a characteristic cross-hatching, as can be seen in the current reconstruction.

Once again, the idea of a bigger, taller temple and pyramid inspired the ruling theocracy and the devout people to embark on a truly titanic work. A still-larger pyramid was constructed over the second pyramid and all of its additions. This would be the true Great Pyramid, as it covered an area measuring more than 1,300 feet on each side. The average height of this monumental structure was almost 213 feet, without counting the height of the temple, which would have been very tall. These characteristics made the great teocalli (possibly dedicated to the god of water or rain) the biggest in the pre-Hispanic world. People from other towns called this sanctuary Tlachihualtepetl, which means “artificial hill” or “manmade hill”.

Large open spaces were created on each side of the great pyramid, bordered by elegantly decorated buildings. Such is the case of the southern plaza, which is known as the “courtyard of altars” owing to the altars and stelae found there, which are made of some type of metamorphic rock and decorated with scrolls that seem to be stylized bird feathers reminiscent of designs from the Gulf coast.

At the end of the eighth century, Mesoamerica experienced a profound change. Its greatest cities began to decline and some were abandoned. The holy city of Tlachihualtepetl suffered wars and calamities, and the crisis was accelerated by an eruption from the volcano of Popocatépetl. The great ceremonial center was destroyed, sacked and later abandoned. The buildings began to be covered by the dirt from the adobe as it crumbled. Little by little, grass and trees began to grow, until it all took on the appearance of a desolate hill. Many years later, some small buildings such as altars and tombs were constructed on the abandoned platforms, but these had no connection to the ancient sanctuary.

Not long after the disaster, the survivors (together with the invaders) built a new ceremonial center where the main square of the city of San Pedro Cholula now lies. This was a place that managed to regain its lost grandeur and splendor. It was there that the conqueror Hernán Cortés carried out one of the cruelest slaughters recorded in human history in order to intimidate the Tenochca.

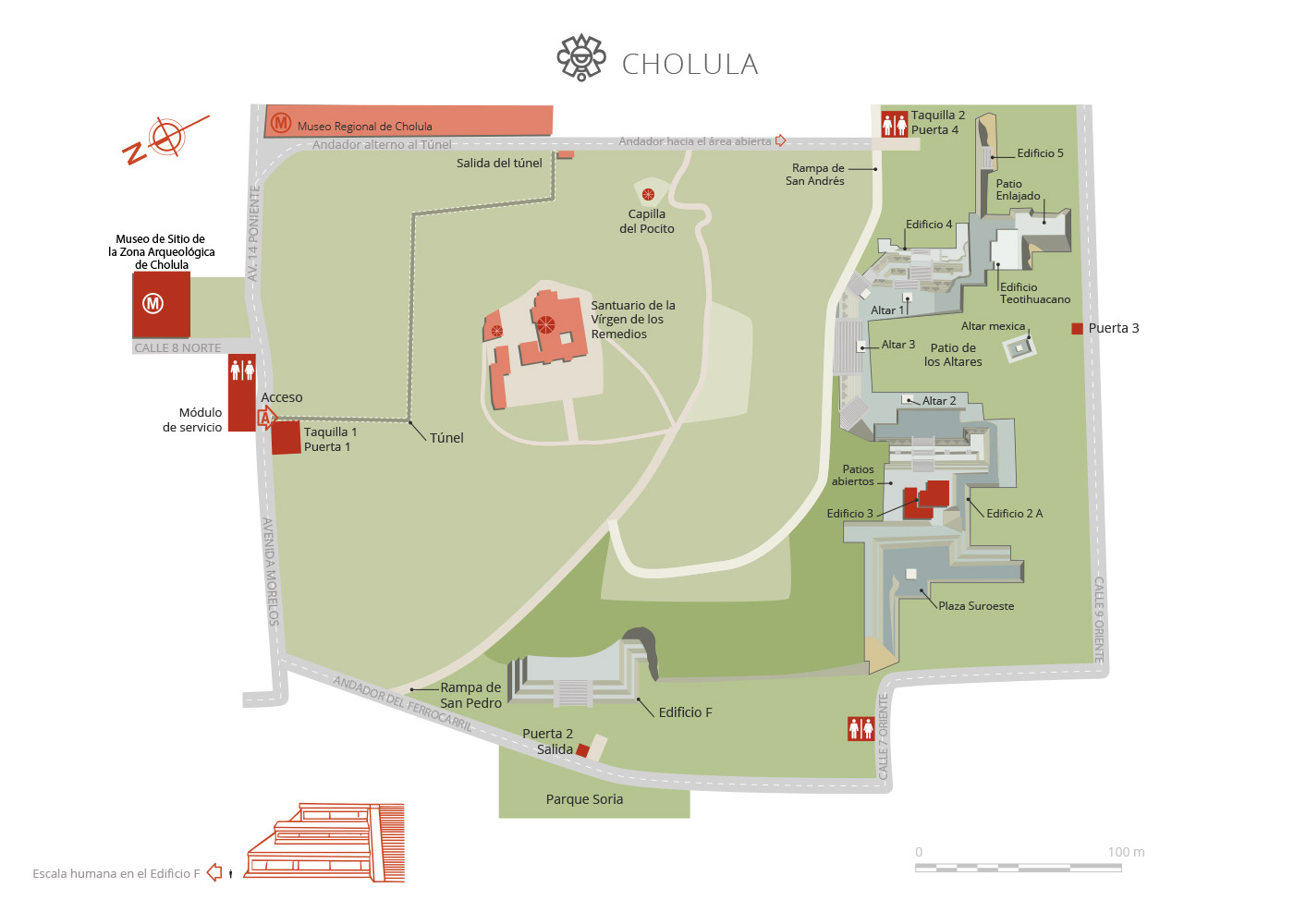

Map

Did you know...

- The courtyard of the altars is the most spectacular part of the archeological zone, above all for the great harmony and proportions of the buildings around it, which display elegant scapulary work on their respective recessed panels.

- Besides the archeological zone, Cholula is home to several colonial buildings of great merit, such as the Royal Chapel, the Franciscan convent, the arcade on its central plaza, the San Andrés parish church and the famous churches of Tonanzintla and Acatepec.

An expert point of view

Eduardo Merlo Juárez

Centro INAH Puebla

Practical information

Wednesday to Sunday from 09:00 to 18:00 hrs. Last entry 17:00 hrs.

$100.00 pesos

El tunel se encuentra cerrado

Se localiza dentro del área urbana de Cholula, 10 kilómetros al poniente de la ciudad de Puebla.

From Mexico City, take Federal Highway 150 Mexico-Veracruz and follow the exit to the south for Cholula.

From the city of Puebla, take the direct road to Cholula.

Public transport is available.

From the city of Puebla, take the direct road to Cholula.

Public transport is available.

Services

-

+52 (222) 235 1478

Directory

Administrador de la Zona Arqueológica y Museo de Sitio

Martín Cruz Sánchez

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (222) 247 9081