The first references to the Ixtlán del Río (Los Toriles) site are by historians and monks. Together, these provide an outline of the way of life in the region and the location of some pre-Hispanic settlements. According to the material and information obtained, the site’s development began in the Classic period, perhaps in the year 400, and continued through the Postclassic period, until the arrival of the Spanish. At this time, different local groups began to settle, as well as groups who had influence on or connections to other cultural areas, such as the center and north of Mexico in its various stages.

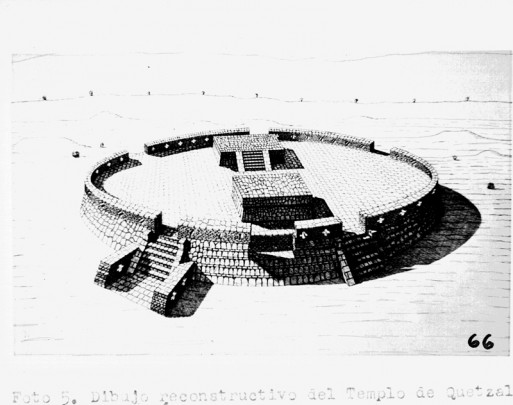

This archeological site was registered again in 1946 by the archeologist and anthropologist José Coruna Núñez, when it received the name Los Toriles de Ixtlán del Río. It is popularly known as the “bullpen” or “bull ring” by the people, becauase of the appearance of the temple dedicated to Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl, which has a circular base. The site covers an area of more than 200 acres and was a city in constant growth. Its inhabitants placed great importance on the city’s buildings which they enlarged or changed over time. Furthermore, they implemented an organized urban layout, with staircases, restricted entrances, open spaces, altars, sidewalks, drains, roads, districts and palaces all over the city, which reached its peak between 700 and 1200.

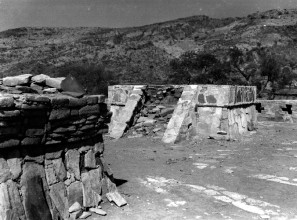

Between the years 300 BC and 600 AD a cultural complex flourished in the area known as the Shaft Tomb tradition. One of its notable characteristics is the underground funerary architecture, which is extremely varied. It has vertical, conical and bottle neck shafts, from 5 to as many as 52 feet in depth, at the end of which are one or several interconnected mortuary chambers. The Shaft Tomb tradition also includes colored ceramic, although it is not as carefully made. This tradition was succeeded by the Aztatlán culture, between 750 and 1100 AD, which included columns, porches, large open spaces, interior courtyards, central altars, roads, carved stones attached to temple walls, as well as staircases and drainage systems. This tradition is also distinguished by its obsidian working using multiple tools, by smooth red pottery for domestic use, and by the gradual abandonment of the ceremonial center.

In 1904, the French anthropologist Léon Diguet and the Norwegian ethnographer Carl Lumholtz embarked on a study of the site and its circular temple, as well as the Ahuacatlán and Ixtlán shaft tombs and the El Tambor (“The Drum”) petroglyphs. The resulting publications, supplemented with photographs, triggered the looting of archeological pieces in the region, which continued until 1970. In 1945, the US anthropologist Edward W. Gifford recorded 16 archeological sites, most of them in the Ahuacatlán valley and San José de Gracia, among them Ixtlán del Río (Los Toriles). The first classification of ceramics in the area was produced by him.

Between 1947 and 1949, José Corona Núñez undertook a full exploration and restoration of the Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl Temple. In his reports, he starts by giving an account of the serious damage done to the monument by the parish priest of Ixtlán, just before 1904, who contrived to make a cut through the center of the building. He also referred to serious damage caused by a detachment of federal soldiers to one of the staircases in 1945, acting on their general’s orders. For seven years, between 1961 and 1967, the archeologist Eduardo Contreras concluded the rescue and restoration of the Palacio de los Relieves (“The Palace of the Bas-reliefs”), the Central Altar and the Palacio de las Columnas (“The Palace of Columns”). After almost twenty years of inactivity, in 1988-1989 the archeologist Raúl Arana restored the intermediate complex of squares and altars known as Section B, where the Recinto Adoratorio (“Enclosed Sanctuary”), the Palacio de las Columnas Superpuestas (“The Palace of Overlapping Columns”), the Cuadro del Hechicero (“The Painting of the Witch”) and the Palacio de los Fogones (“The Palace of Ovens”) are found.

- In general, the Shaft Tombs were reused. After burying one or more individuals, they were reopened to bury others. They assembled the skeletal remains of the first individuals into mounds which they placed at the ends of the mortuary chambers.

- The Aztlán tradition also stood out for its development of metallurgy, of techniques such as lost wax, embossing, rolling and false filigree, which they used to make ornamental and ritual objects and musical instruments.

- The clay pottery is admired for its polychromatic application of red, white, orange, black, yellowish white and brown, which are used to adorn rounded pots, earthenware pots, mortars and elegant vases with exact and symmetrical fretwork patterns, snakes, snails, feathers, waves and crosses.

- Due to the extensive looting, floors made from clay and tiled with fine slabs were broken. Occasionally, the damage was so great that it altered the inner core and the foundations.

- Large volumes of extracted material were used for modern buildings, causing irreparable losses that make the reconstruction of altars, promontories and mounds impossible.

-

+52 (311) 216 3022

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.