The pre-Hispanic city of Tzintzuntzan, located on the shores of Pátzcuaro Lake, was undoubtedly one of the most largest settlements at the time of the Spaniards’ arrival in the sixteenth century. As the capital of the Tarascan state, it was here that the most important political, economic and religious decisions were taken for a large territory. This site was also the residence of the Señores Uacusechas—or “Eagle Lords”—who were rulers of this important domain, where power was handed down dynastically. Tzintzuntzan functioned as “capital of the empire and the valley,” and was also the official royal residence of the Irecha, a ritual center and administrative seat, a regional market, and a center of production for simple artefacts, ritual objects, and high-quality handcrafts.

The unique character of the conquest of Michoacán, which was largely the result of a negotiated agreement, meant that for much of the sixteenth century this city was host to a mixture of Tarascan nobility and Spanish conquistadors in the city’s former location, until it was transferred to lower ground toward the end of the sixteenth century. Tzintzuntzan is therefore a unique subject of investigation into the transition between pre-Hispanic societies and those of the early vice-regal period.

The ancient city of Tzintzuntzan stretches across wide terraces and extensive platforms ranged along the sides of the Yarahuato and Tariaquere hills, providing a base for sizeable archeological structures. When the Spaniards arrived, the site had an estimated population of 30,000. Many doubts remain as to the city’s exact age, but based on the materials recovered during the archeological explorations and the typologies found so far, its occupation can be dated back to at least the Late Classic (600-1000 AD).

A little historical background is warranted to determine the Uacusechas’ arrival in Tzintzuntzan. Tariacuri, the cultural hero of the “Relación de Michoacán” saga who unified the Tarascan state and governed Pátzcuaro, established three seats of power: Pátzcuaro, Ihuatzio and Tzintzuntzan. Then he distributed them between his son and two of his nephews: Hiquingare, Hirepan and Tanganxoan, respectively. Upon the death of Hirepan, ruler of Ihuatzio, Tzintzuntzan became the most important city in the first half of the fifteenth century. According to the “Relación de Michoacán” it was Tanganxoan I who “rebuilt” this city on the orders of the goddess Xaratanga, as it seems she was no longer being worshipped.

After Tanganxoan’s death, Tzitzispandacuare (1454-1479) took over power, and he transferred the main Tarascan god, Curicaueri, together with his offerings, to the city. He also expanded the empire, making incursions into the valley of Toluca and Xocotitlán, as well as Colima and the city of Zacatula in Guerrero. His descendant, Zuangua (1479-1520), continued the state’s territorial expansion and consolidated its eastern boundaries. Zuangua knew about the conquistadors’ arrival in Tenochtitlan, but died shortly before the first Spaniards reached Michoacán. In the end it was Tzinzincha Tanganxoan II (1510-1530)—while still a very young man—who negotiated the handover of the territory with Cristóbal de Olid; he died soon afterwards at the hands of Nuño de Guzmán, after facing an unfair trial and being subjected to torture.

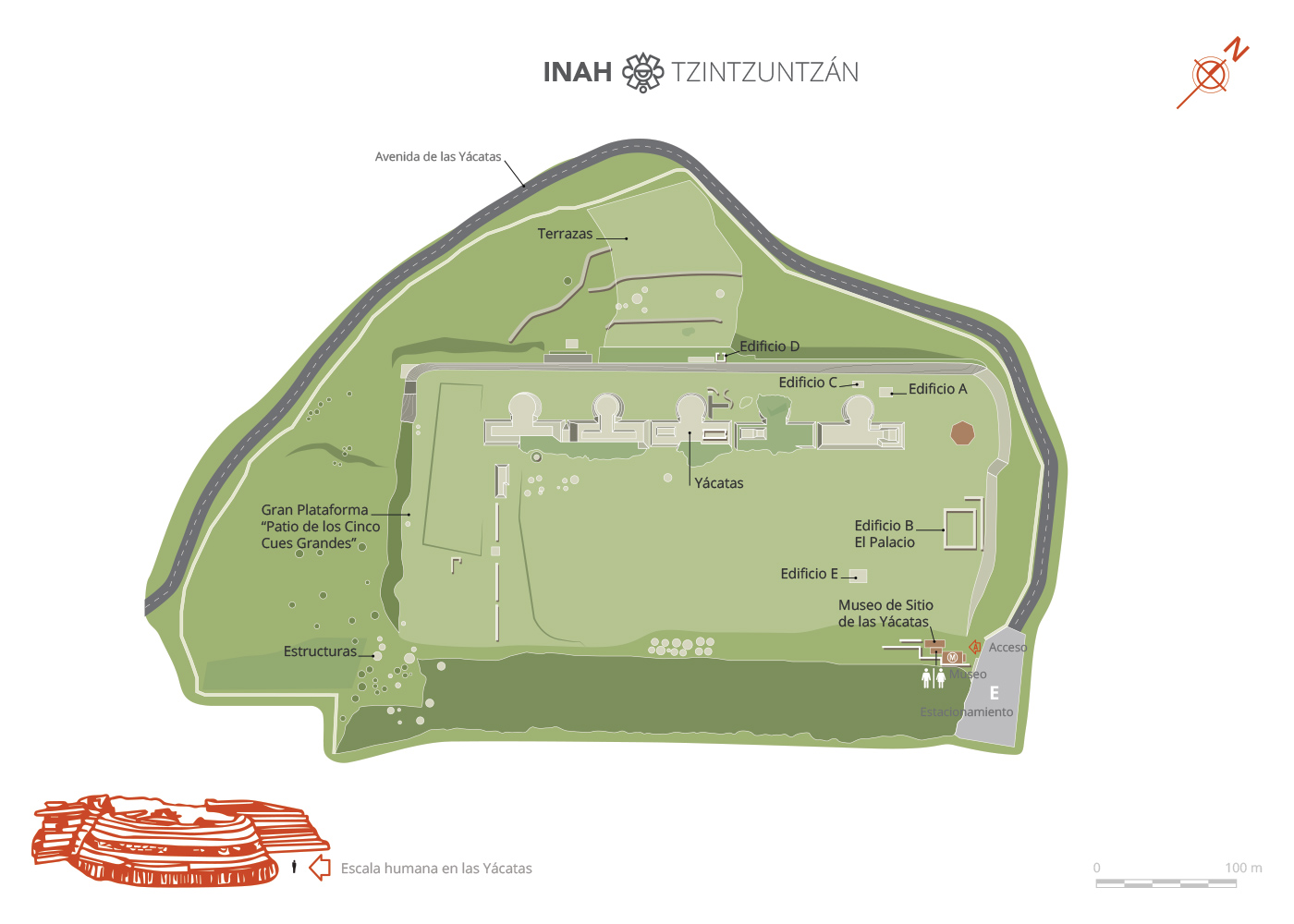

Current archeological explorations in Tzintzuntzan have been focused on the area of the Gran Plataforma ("Great Platform") and the platform known as La Tira. The Great Platform provides the base for five of the semi-circular “yacata” structures, in addition to other structures, notably Building B, also known as the Palace, which is a series of rooms distributed around a courtyard that must have once had columns to hold up the roof of a possible corridor.

Other spaces are referred to in historical accounts but have not been found by archeologists. These include La Casa de las Águilas (“The House of the Eagles”), Casa de las Plumas de Papagayos (“House of the Parrot Feathers”), Casa de las Plumas de Gallina/Guajolote (“House of the Chicken/Turkey Feathers”), the ballcourt, the baths known as “Puque huringuequa,” where sacrifices were made to the gods of the left hand known as the “Viranbanecha”; plus a zoo, a prison, the market, and the trojes, granaries where the lords’ personal belongings were kept, as well as crop harvests.

- The Uacusecha’s most important deity was the sun god Curicaueri. The main offering to him was fire, which had to be kept permanently lit in the temples and on the “yacata” pyramids.

- In 1888, Nicolás León, a leading scholar from Michoacán, published the results of the first explorations and studies of Tzintzuntzan.

-

+52 (443) 313 2650 ext. 248004

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.