Tenochtitlan was the Mexica’s religious and political center, and their Huey Teocalli or Great Temple was the most important building of this vast pre-Hispanic city. The site was believed to be the confluence of the four cardinal points of the earth and the axis of the three levels of life: the sky, the earth, and the underworld.

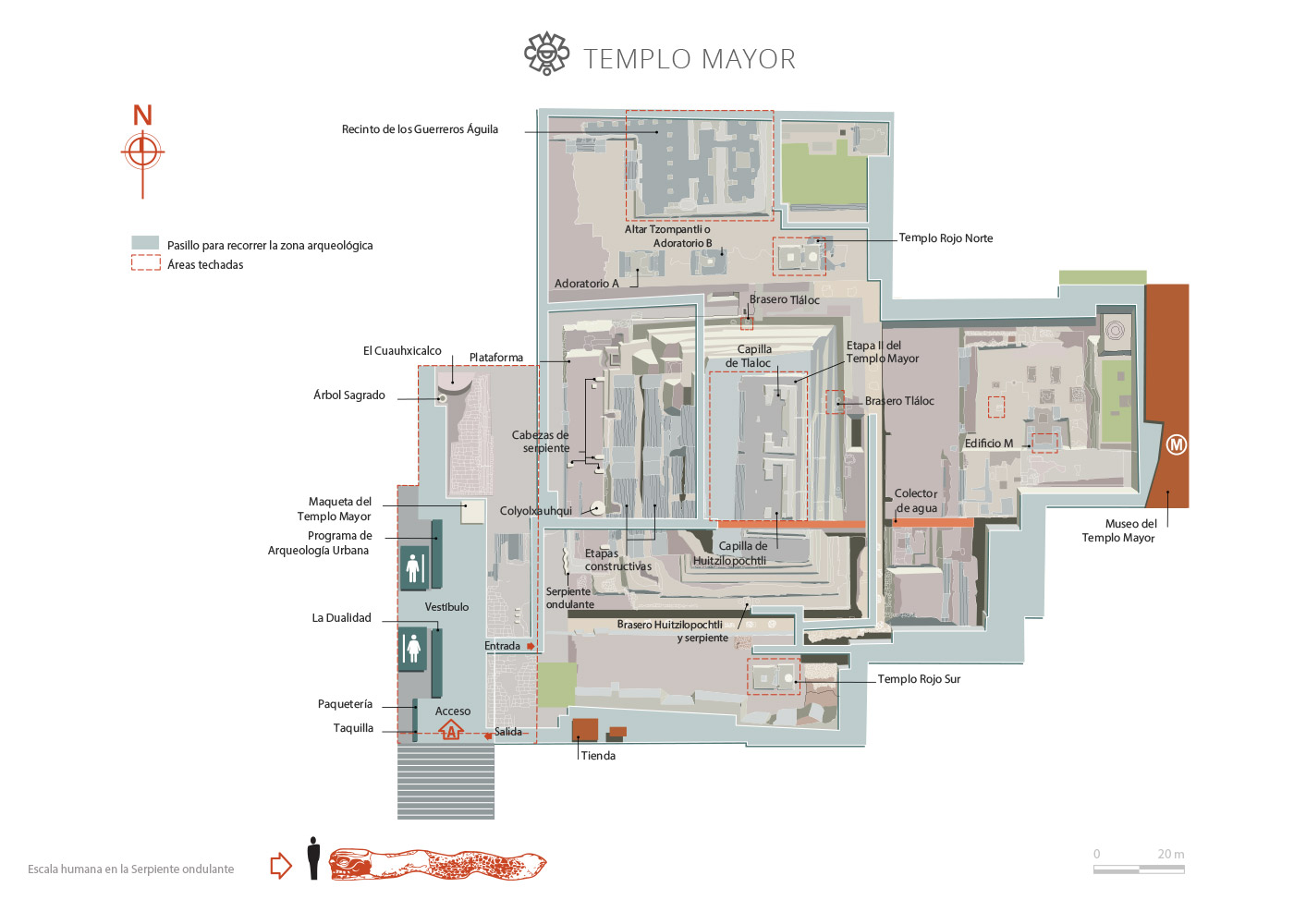

The Templo Mayor was expanded seven times; the final iteration, the one seen and destroyed by the Spanish, was an imposing 150 feet high and had a square base with each side measuring 440 yards. The pyramid had two large flights of steps leading to its uppermost part, in front of each of the two temples dedicated to the Mexica’s principal Gods: one temple was built to the north, in honor of Tlaloc (“nectar of the earth”), god of rain and agriculture; and the other to the south, as a shrine to Huitzilopochtli (“left-hummingbird” or “resuscitated warrior”), god of war. With each new extension, the Mexica declared a “flower war”—a ritual war waged against an enemy people in order to take captives and sacrifice them on the day the renovated temple was to be consecrated.

Two sacred mountains were represented in the Huey Teocalli: to the north, Tonacatepetl, hill of sustenance, a food store; and, to the south, Coatepec, hill of serpents and birthplace of Huitzilopochtli.

Opposite the large pyramid stood the circular-based shrine of Ehecatl, the god of wind (a title of Quetzalcoatl). And on the southern edge the tzompantli altar was erected, with an elongated rectangular base on top of which, skewered on pieces of timber held up with tall stakes, were the heads and skeletons of thousands of sacrificial victims and also, it seems, warriors who had died in battle. In front of the Huey Teocalli was the Palace of Axayacatl, residence of Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, a building subsequently occupied by the recently arrived “visitor,” Hernán Cortés.

The main causeways connecting Tenochtitlan to terra firma converged at the Templo Mayor: the road to Iztapalapa to the south, with a branch leading to Coyoacán; the way to Tacuba (Tlacopan) lay to the west and Tepeyac (Tepeyácac) to the north.

The last of the Chichimecs, the Mexica were a people who spent many years spent migrating through Mesoamerica’s northern regions before eventually establishing themselves permanently in the Valley of Mexico. According to historical sources, they claimed to have come from an island on a lake called Aztlan, and they left that site in search of a better place in which to settle on the instructions of their guardian god, Huitzilopochtli.

The location of Aztlan has been a subject of controversy among researchers of pre-Hispanic Mexico, with some believing it was a mythical place that never actually existed, but used by the Mexica to legitimize their past. Others, meanwhile, have attempted to locate it geographically in the north of Mexico’s central highland region.

The date on which Tenochtitlan was founded has also been debated, though most scholars agree on the date 2 Calli, which corresponds to the Common Era date of 1325 AD. Its foundation is accompanied by a whole series of symbols and myths to distinguish this spot chosen by the Mexica’s god for their city. However, there must also have been a predominantly military and economic reason for choosing this area, since the lakes provided a vast range of products and could be defended easily.

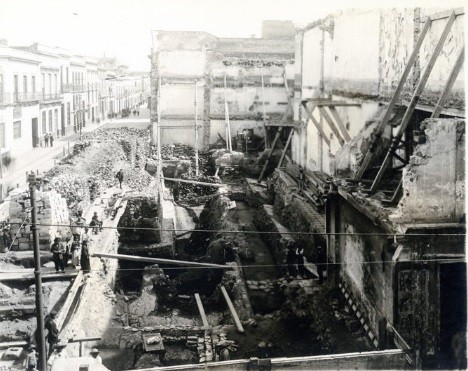

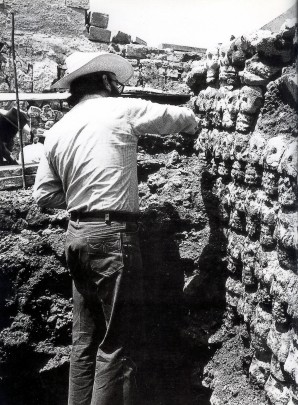

In 1914, historian and archeologist Manuel Gamio discovered the south-western corner of the temple and part of a set of steps, pinpointing the location of the Huey Teocalli. Subsequently, in 1978, the fortuitous discovery of the monolithic Moon God, Coyolxauhqui, triggered one of the twentieth century’s most important archeological projects, led by archeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma and a multidisciplinary team that worked tirelessly during an initial excavation stage from 1978 to 1982, recovering the remains of Tenochtitlan’s Templo Mayor.

With the findings of more than 7,000 objects during that initial stage of exploration, on October 12, 1987, the doors were opened to the Templo Mayor site museum, designed by architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez.

- In 1790, the Coatlicue and Sun Stone sculptures were found in Mexico City’s main square, now known as the Zócalo.

- In 1792, the first book on archeology was published in Mexico. Written by Antonio de León y Gama, it was called “Descripción histórica y cronológica de las dos piedras” ("Historical and chronological description of the two stones").

- Thanks to the intervention of Bishop Feliciano Marín, Alexander von Humboldt was able to study the Sun Stone; after he completed his work the sculpture was reburied.

- In 1877, a publication called “Annals of the National Museum" included an article written by Manuel Orozco Berra called “The Dedication of Mexico’s Templo Mayor," about the green headstone carved in 1487 to commemorate the completion of one of the construction phases of a Mexica temple.

https://ventadeboletosenlinea.inah.gob.mx/

-

+52 (55) 4040 5600

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

WWW

-

FACEBOOK