Santa Rosa Xtampak is one of the most important Mayan cities in northeastern Campeche. The labor required to build and maintain its pyramids, palaces and temples points to the existence of a solid political structure that controlled a wide region. The rulers also ordered the creation of official inscriptions on the stelae and paintings found on various chambers; they established long-distance trade links and played an important role in the area, especially during the Late Classic (600-900 AD). The eight stelae registered at the site to date bear dates ranging from 646 to 911 AD.

The name of the archeological site combines two words: Santa Rosa, the name of a nineteenth-century hacienda, where pre-Hispanic remains or “xlabpak” (old walls in Yucatec Mayan) were found. The placename was used throughout the nineteenth century (when it was known as Xlabpak de Santa Rosa), and in the following century it was modified to Santa Rosa Xtampak (“opposite the wall,” “exposed wall”), in reference to the walls conserved on one of the main buildings.

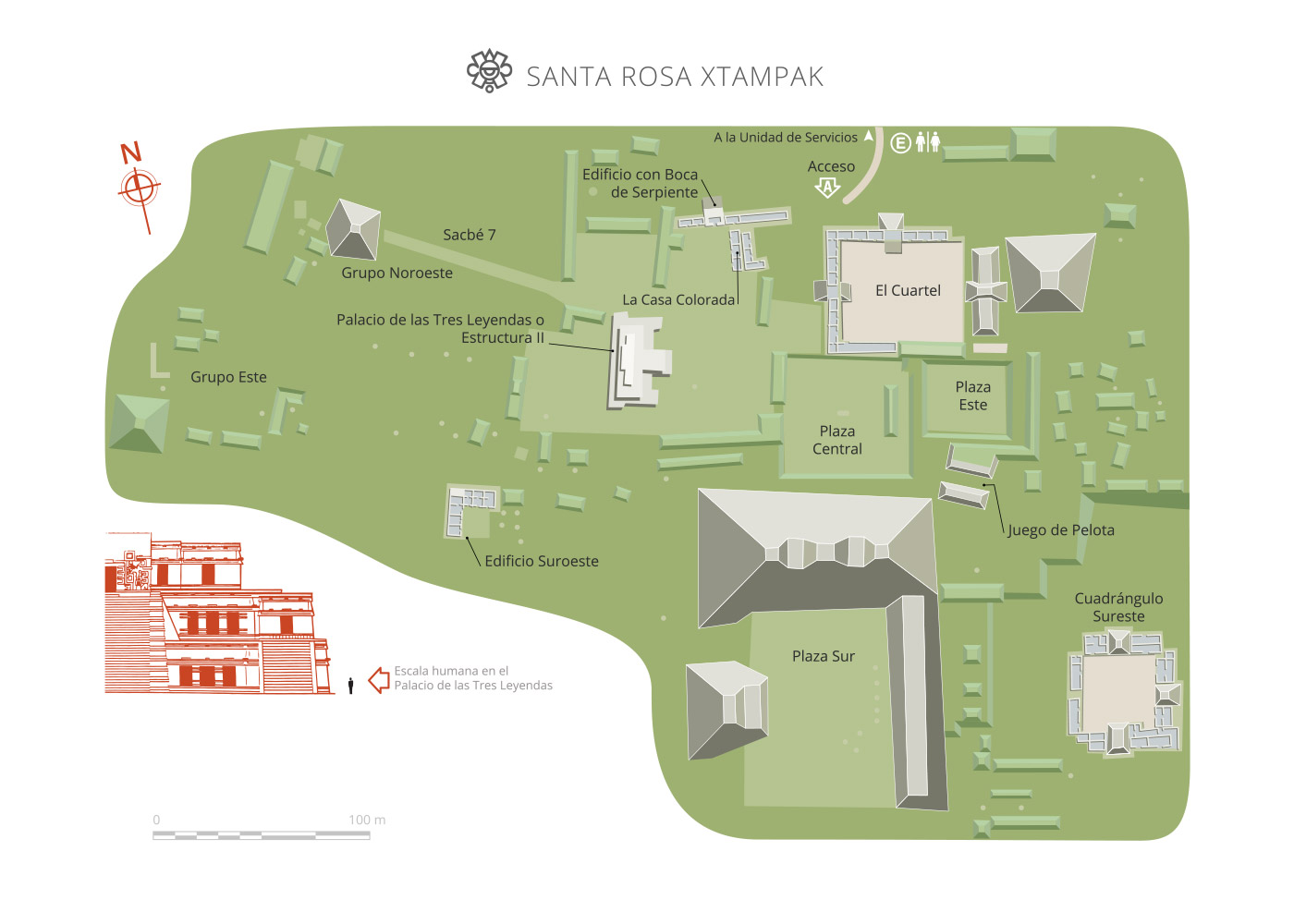

The remains of this Mayan city are located at the top of a hill, which was leveled in various parts and given terraced slopes in order to enable the construction of around a hundred masonry buildings, many on a monumental scale, and these created several regularly distributed square patios and plazas.

Eight stelae have been found at Santa Rosa Xtampak, as well as an altar and several painted vault covers containing invaluable information in their images and hieroglyphic inscriptions. Therefore we know that the earliest date yet recorded is 646 AD (Stela 5), although preliminary analyses of the pottery indicate that the settlement existed several centuries before the Common Era. The most recent date—948 AD—was discovered by specialists on the cover of a vault in the Palace building. The pottery artefacts also point to a diminished occupation by the Post Classic (1000-1500 AD), before the site was completely abandoned before the Europeans landed on the peninsula.

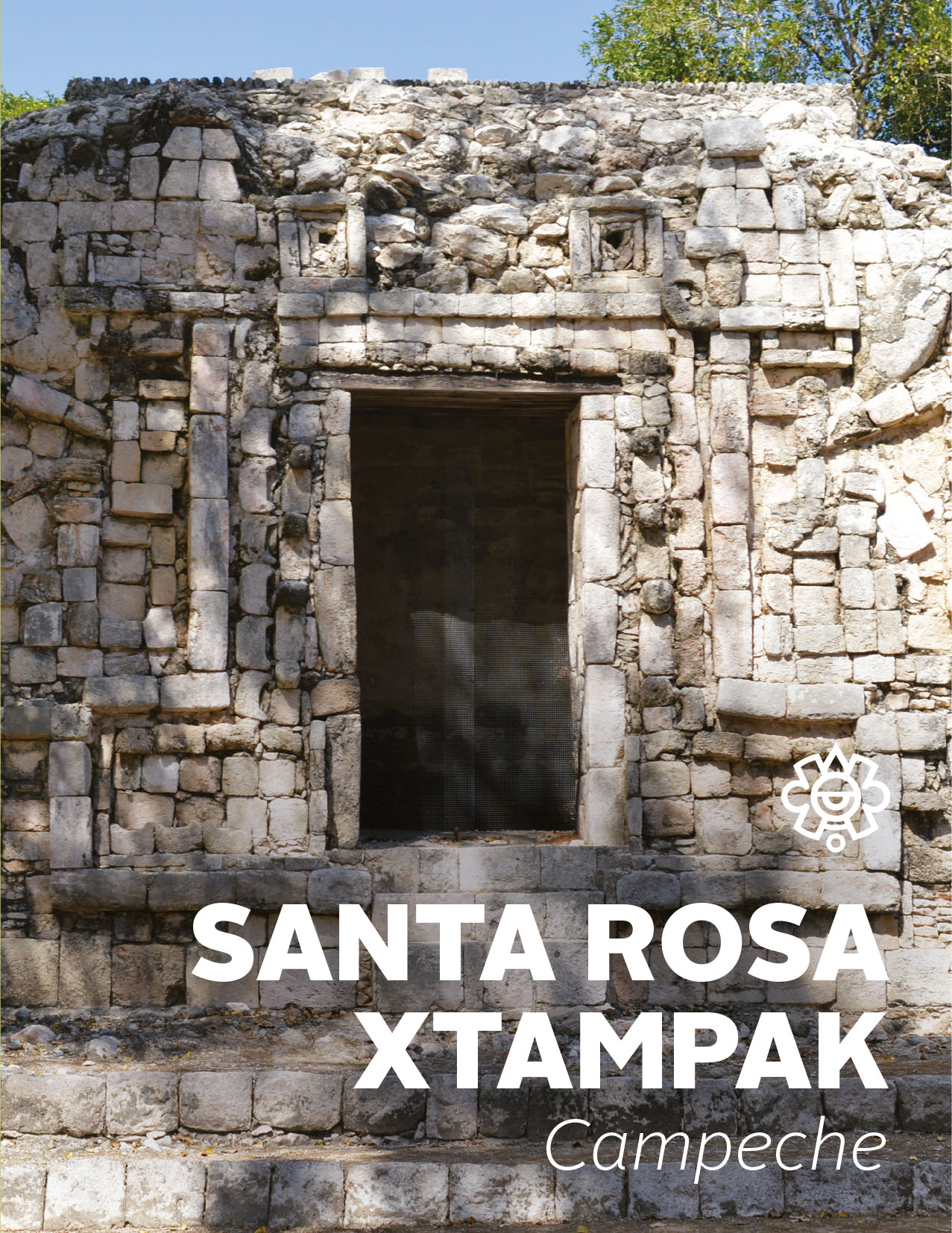

Chenes is the predominant architectural style in Santa Rosa Xtampak, where the constructions are noted for their large mask decorations that partially or completely cover the main facades. The motifs were created using specially cut stone mosaics that were then coated in stucco and painted in various colors, above all red. Many of the buildings combine smooth wall surfaces with columns set into the walls or corners. The many entrances are usually formed by masonry columns or pillars. The arch vaults generally begin directly from the vertical wall supporting them, almost without leaving even the slightest set back or soffit. The internal setbacks over the lintels are also common features.

Water was supplied using an extensive system of chultuns or underground cisterns for rainwater collection. Evan DeBloois studied 67 chultuns and by calculating the maximum rainwater collection capacity, conservative estimates suggest that the city could have supported an average population of 10,000 inhabitants.

The site was first brought to the world’s attention by the explorers Frederick Catherwood and John L. Stephens, who visited it in the mid-nineteenth century. Soon before the end of that century, Teobert Maler conducted a more detailed survey of the remains. In the 1930s and 40s, various researchers from the Carnegie Institution, led by Harry Pollock, carried out archeological work at Santa Rosa. In the late 1960s, Richard Stamps and Evan DeBloois, of the Brigham Young University in Utah, recorded and analyzed the site’s architecture, ceramics and chultuns. More specialists arrived in the 1980s: George Andrews (University of Oregon) and Paul Gendrop (UNAM) carried out architectural studies, while William Folan and Abel Morales (Autonomous University of Campeche) came to draw up plans of the settlement’s layout. In the 1990s, Nicholas Hellmuth produced a highly detailed photographic record of the buildings still standing; Hasso Hohmann and Erwin Heine made a photogrammetric study of the Palace and carried out some initial architectural restoration works under the supervision of Antonio Benavides C. In the beginning of the twenty-first century, Renée Zapata coordinated a maintenance program for some of the main constructions.

- For 850 years, the former settlement of Santa Rosa Xtampak underwent an admirably well-ordered urban expansion.

- The site’s decline seems to have begun between 1000 and 1200 AD. However, it continued to be an important landmark for local inhabitants.

- The architectural, ceramic, pictorial and epigraphic elements found at the site lead us to believe that it was the capital of the Chenes region, and maintained close ties with other, very different areas.

- The Chenes and Río Bec styles used in writing and decorative elements suggest that these were used to express the power of the city's inhabitants.

-

+52 (981) 816 9111 Ext. 138016

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

FACEBOOK

-

TWITTER