Museo Local Valle de Tehuacán

According to Justo Sierra, the ancient Mexicans were people of corn. This plant of humble origins was domesticated and greatly improved over the course of a long and astonishing social and biological history, as set out in this museum, together with the ancient figures of pre-Hispanic gods.

Local

About the museum

This museum tells the Mesoamerican people’s story of maize. Opened in 1967, and reinaugurated with a new exhibition in 2003, it is located in the El Carmen Cultural Complex (a former eighteenth-century Carmelite monastery) which also includes the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, the Mineralogy Museum, the public library and the municipal offices of Tehuacán. This space tells the story of the development and the importance of maize in the process of settlement in Mesoamerica over the course of 7,000 years. Among the most important pieces are ancient ears of teosinte, the primitive version of maize.

In 1960 the American archeologist Richard S. MacNeish completed his work on Cañada de Tehuacán, or more specifically on the Caves of Coxcatlan (“place of the jeweled necklaces”) and Texcal (texcatl or mirror) where the oldest specimens of teosinte (teocintle, teocintli: “the divine ear of maize”), the wild ancestor of maize were found, dating back 5,000 years. Soon afterwards a decision was taken to set up a gallery to display these and other finds from the site. The Town Hall of Tehuacán granted use of the former monastery of Nuestra Señora del Carmen, of which the church was still in use, while other parts of the building were allocated to the fire department and the Red Cross.

The Museum of Maize was set up in 1967, later becoming the Museum of the Valley of Tehuacán, under the direction of architect and archeologist Miguel Messmaher. The remains of an ancient garden were revived and renovated as a botanical garden to demonstrate the life cycle of the maize plant, alongside other plants discovered in the caves such as chili, beans, amaranth, avocado, agave, gourds and nopal cactus.

Various gallery spaces were installed in the monastery to display original samples of teosinte, and a series of photographs of the excavations of Cañada de Tehuacán, with representations of the deities illustrated in a number of pre-Hispanic and post-Conquest codices. To these were added archeological finds, knives, scrapers and other artifacts, including some brought from other regions, or given by private donation.

The violent earthquake which shook the region on August 28, 1973 caused severe damage to the building and the annexed church. Fortunately it was possible to reinforce the damaged parts and to restore its stability. One of the highlights of the restored space is the mural of the goddess Centeotl, the maize deity, an ingenious and skillfully made image using pieces of dried corn.

Pride of place is given to the metates (grinding stones) and their tecolotes (pounding stones) which show the wear caused by intense friction over many years, since these were essential to the process of making the highly nutritional nixtamal corn dough to an ancient recipe that included lime, which is rich in calcium. Nixtamal is the basis for all the uses of this wonderful grain.

A special showcase includes the region’s most spectacular finds: some wooden masks which were covered in tiny pieces of mosaic made from turquoise, jade, shell and other precious materials together with some chimallis (warrior’s shields), which were also decorated with rich appliqué. These came from the mountains close to the town of Santa Ana Teloxtoc (from tetloztoc, meaning cave of the stones), and they are dated to the Postclassic horizon around the fifteenth century.

There is a special place for the terracotta “xantiles,” figues of gods and warriors. The term derives from “santo” (Spanish for saint) or “xanto” as pronounced by the natives. Xantiles are typical of the Tehuacán region (“place of the gods”). There are also some small figurines on display representing an array of indigenous gods. They were found together with some models of teocallis in the Tehuacán region of Calipan (“the house in the heights”). There is also a very varied collection of vessels in different forms, since Cañada, which is part of the Tehuacán region, has long been home to excellent potters.

The barefoot Carmelite friars began to arrive in New Spain in 1585. They founded their first monasteries in Mexico City, Puebla and at Atlixco. When one of them passed through Tehuacán on his way to Oaxaca in the eighteenth century, the local Spanish inhabitants asked him to found a monastery there, since Tehuacán was the most important of the region’s towns, with nearly three thousand Spanish and creole inhabitants and the same number of mestizos and indigenous people. The landowner Juan del Moral donated the funds for construction. It was approved by the bishop of Puebla Pedro Nogales Dávila, and it was accepted – the second time around – by the Viceroy the Marques of Casa Fuerte. It was founded in 1747 under the supervision of Fray José de la Concepción, being upgraded from the original idea of a hospice to a formal monastery.

The barefoot Carmelites were in charge of the monastery until 1857 when they were evicted in a peremptory manner during the violent episode that accompanied the implementation of the Reform Laws, after the war between liberals and conservatives. There was widespread looting and pillaging during this chaotic time with the loss of the majority of the altarpieces, sculptures, paintings, books and furniture. The bare and empty monastery was abandoned, but more than 100 years later it was handed over to be the Valley of Tehuacán Museum.

Today the museum space is reduced since the municipality has asked for the donated building to be returned, and has occupied the upper stories.

In 1960 the American archeologist Richard S. MacNeish completed his work on Cañada de Tehuacán, or more specifically on the Caves of Coxcatlan (“place of the jeweled necklaces”) and Texcal (texcatl or mirror) where the oldest specimens of teosinte (teocintle, teocintli: “the divine ear of maize”), the wild ancestor of maize were found, dating back 5,000 years. Soon afterwards a decision was taken to set up a gallery to display these and other finds from the site. The Town Hall of Tehuacán granted use of the former monastery of Nuestra Señora del Carmen, of which the church was still in use, while other parts of the building were allocated to the fire department and the Red Cross.

The Museum of Maize was set up in 1967, later becoming the Museum of the Valley of Tehuacán, under the direction of architect and archeologist Miguel Messmaher. The remains of an ancient garden were revived and renovated as a botanical garden to demonstrate the life cycle of the maize plant, alongside other plants discovered in the caves such as chili, beans, amaranth, avocado, agave, gourds and nopal cactus.

Various gallery spaces were installed in the monastery to display original samples of teosinte, and a series of photographs of the excavations of Cañada de Tehuacán, with representations of the deities illustrated in a number of pre-Hispanic and post-Conquest codices. To these were added archeological finds, knives, scrapers and other artifacts, including some brought from other regions, or given by private donation.

The violent earthquake which shook the region on August 28, 1973 caused severe damage to the building and the annexed church. Fortunately it was possible to reinforce the damaged parts and to restore its stability. One of the highlights of the restored space is the mural of the goddess Centeotl, the maize deity, an ingenious and skillfully made image using pieces of dried corn.

Pride of place is given to the metates (grinding stones) and their tecolotes (pounding stones) which show the wear caused by intense friction over many years, since these were essential to the process of making the highly nutritional nixtamal corn dough to an ancient recipe that included lime, which is rich in calcium. Nixtamal is the basis for all the uses of this wonderful grain.

A special showcase includes the region’s most spectacular finds: some wooden masks which were covered in tiny pieces of mosaic made from turquoise, jade, shell and other precious materials together with some chimallis (warrior’s shields), which were also decorated with rich appliqué. These came from the mountains close to the town of Santa Ana Teloxtoc (from tetloztoc, meaning cave of the stones), and they are dated to the Postclassic horizon around the fifteenth century.

There is a special place for the terracotta “xantiles,” figues of gods and warriors. The term derives from “santo” (Spanish for saint) or “xanto” as pronounced by the natives. Xantiles are typical of the Tehuacán region (“place of the gods”). There are also some small figurines on display representing an array of indigenous gods. They were found together with some models of teocallis in the Tehuacán region of Calipan (“the house in the heights”). There is also a very varied collection of vessels in different forms, since Cañada, which is part of the Tehuacán region, has long been home to excellent potters.

The barefoot Carmelite friars began to arrive in New Spain in 1585. They founded their first monasteries in Mexico City, Puebla and at Atlixco. When one of them passed through Tehuacán on his way to Oaxaca in the eighteenth century, the local Spanish inhabitants asked him to found a monastery there, since Tehuacán was the most important of the region’s towns, with nearly three thousand Spanish and creole inhabitants and the same number of mestizos and indigenous people. The landowner Juan del Moral donated the funds for construction. It was approved by the bishop of Puebla Pedro Nogales Dávila, and it was accepted – the second time around – by the Viceroy the Marques of Casa Fuerte. It was founded in 1747 under the supervision of Fray José de la Concepción, being upgraded from the original idea of a hospice to a formal monastery.

The barefoot Carmelites were in charge of the monastery until 1857 when they were evicted in a peremptory manner during the violent episode that accompanied the implementation of the Reform Laws, after the war between liberals and conservatives. There was widespread looting and pillaging during this chaotic time with the loss of the majority of the altarpieces, sculptures, paintings, books and furniture. The bare and empty monastery was abandoned, but more than 100 years later it was handed over to be the Valley of Tehuacán Museum.

Today the museum space is reduced since the municipality has asked for the donated building to be returned, and has occupied the upper stories.

January 1967

January 2003

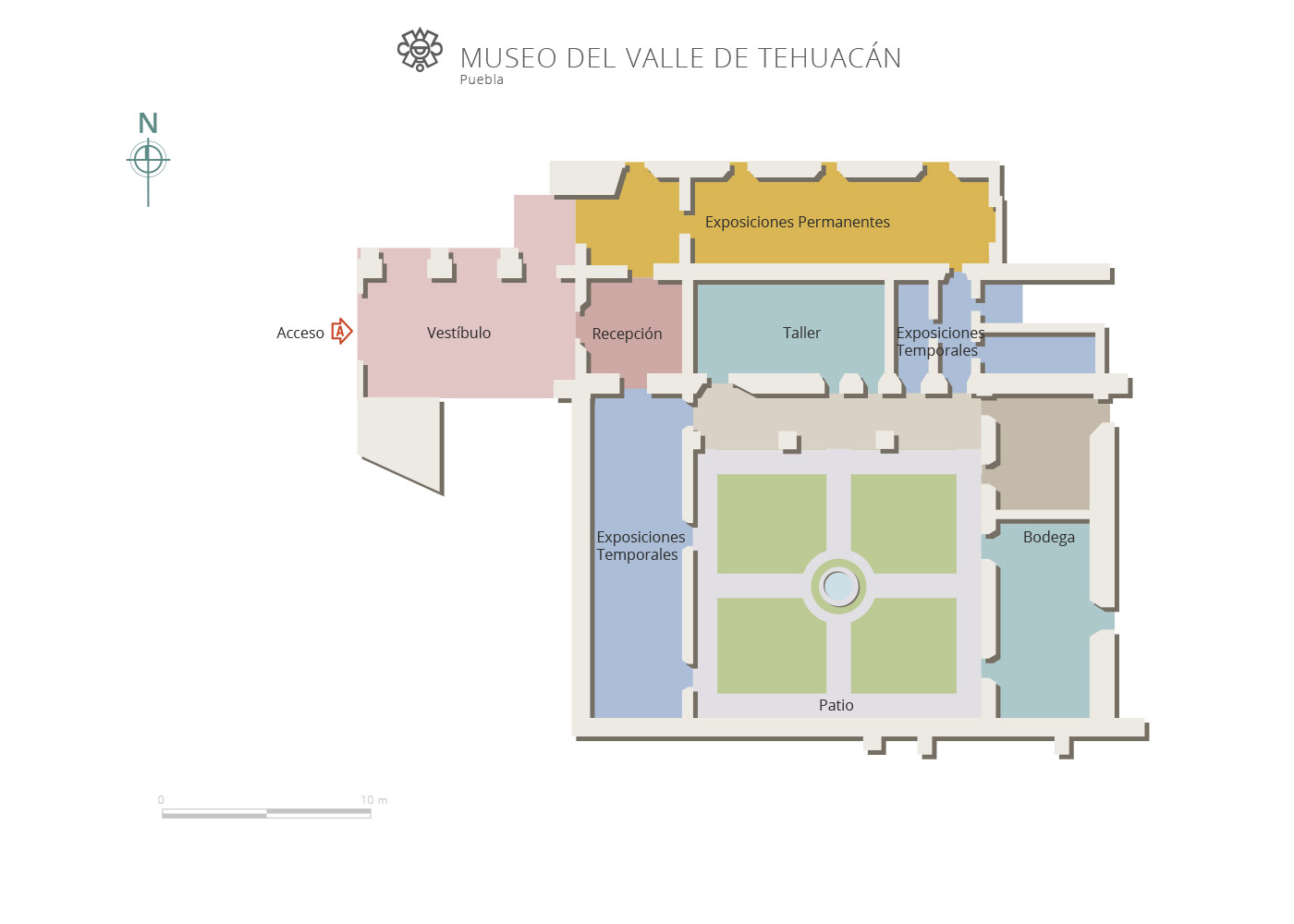

Map

Practical information

Tuesday to Sunday from 10:00 to 17:00 hrs.

$75.00 pesos

Reforma Norte No. 200,

Colonia Centro, C.P. 75700,

Tehuacán, Puebla, México.

Colonia Centro, C.P. 75700,

Tehuacán, Puebla, México.

Services

-

+52 (238) 382 4045

Directory