Museo del Fuerte de Guadalupe

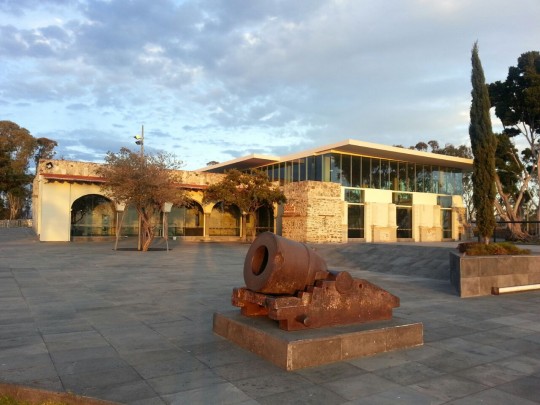

“The nation’s arms are covered in glory” wrote general Zaragoza in his war report. He commanded the infantry and the forts of Loreto and Guadalupe. The fort of Guadalupe’s exhibitions tells its own story, victory at the Battle of Puebla and the triumph of the Republic.

Historic place

About the museum

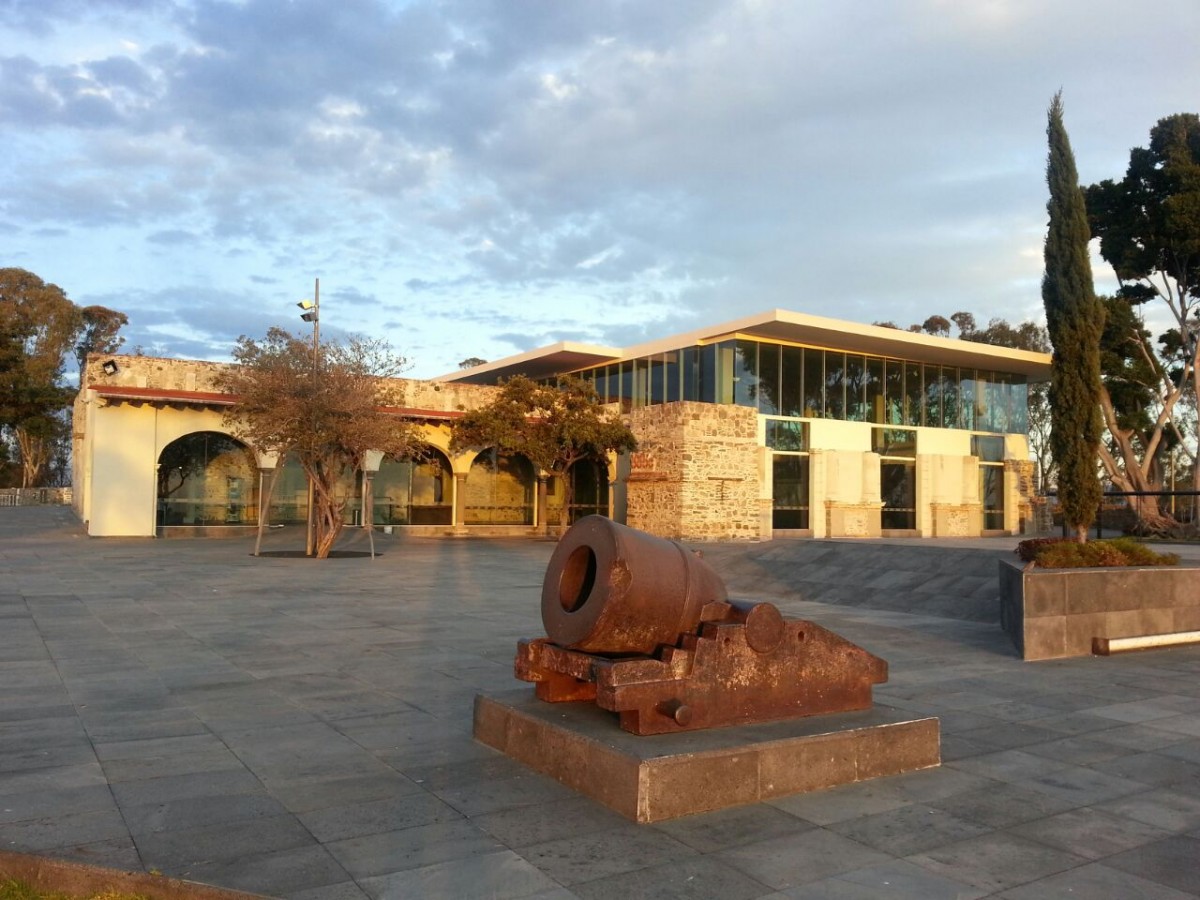

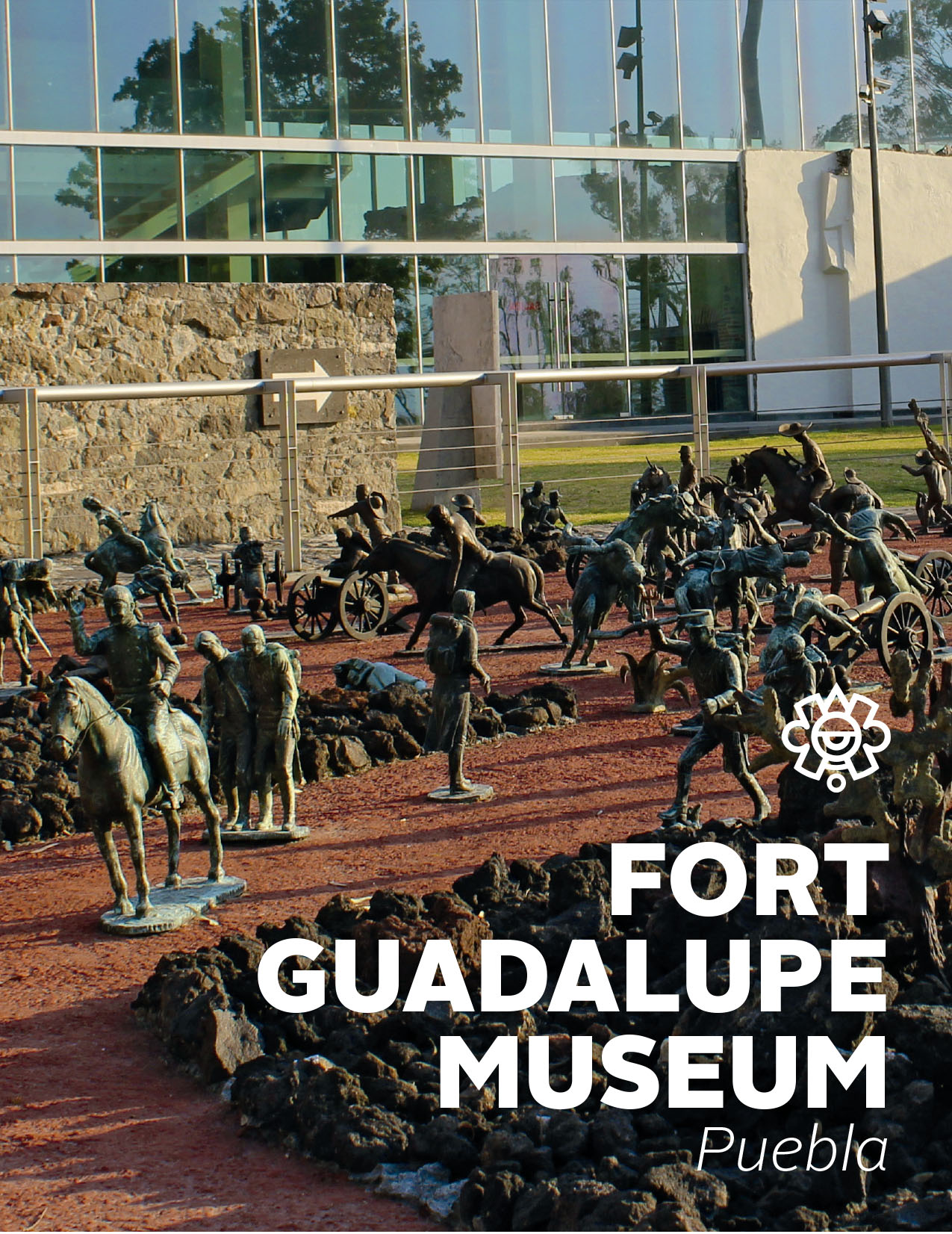

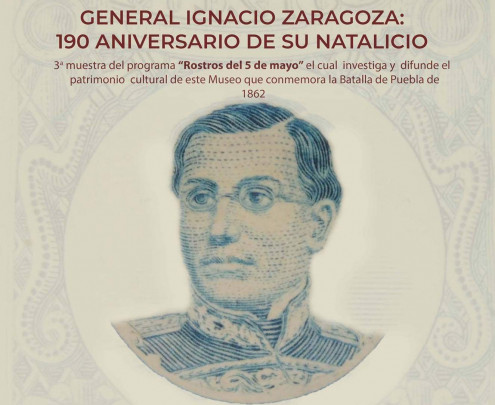

The museum commemorates the Battle of Puebla of May 5, 1862, (“Cinco de Mayo”) against the invading army of the Second French Empire. The Fort of Guadalupe is emblematic of the city of Puebla as it, alongside the Fort of Lareto, was the site of the battle in which the forces of the eastern army of the Mexican republic triumphed under the command of General Ignacio Zaragoza. It is also closely linked to other museums, an auditorium and a conference center. The historical restoration of the site began on January 15, 1962, covering this fort, the fort of Loreto and the construction of the Cinco de Mayo Centenary Civic Center. Today the modern interactive museum tells the story of General Zaragoza’s victory, giving the history of the building over several stages: the Hermitage of San Cristóbal in the sixteenth century, the Church of Our Lady of Belén in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a basilica-shaped church in honor of the Virgin of Guadalupe consecrated in 1816, and a republican fort in the Battle of Puebla.

The building was already well preserved as a historical monument, but it was consolidated as a museum under the Comprehensive Rehabilitation Project of the Forts Area carried out by the government of Puebla, supported by the Defense Ministry and INAH on September 8, 2012. A site gallery safeguards a collection of about 180 items, which commemorate and elucidate the victory of the Republic. Its launch coincided with the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Puebla, and it also commemorated the death of General Zaragoza from typhoid soon after the battle, on September 8, 1862.

The background to these events is extensive. Historical research by Celia Salazar Exaire has revealed that the hill where the Fort of Guadalupe was sited was known by the pre-Hispanic inhabitants as Acueyametepec, meaning the hill covered by agave cactus with an abundance of frogs. Once the city of Puebla had been founded in 1537, the Franciscans headed by Fray Toribio de Benavente built a hermitage dedicated to San Cristóbal. Years afterwards, when it had already been converted into a church, the Bethlehemite Brothers, an order of teachers and nurses founded in Guatemala in 1656, arrived at the shrine and before the turn of the century added a hospital building. From then onwards instead of being known as the church of San Cristóbal it was known as the church of Belem (Bethlehem). In 1756 an earthquake hit the city of Puebla, extensively damaging the church. It had to be rebuilt, and reopened its doors in 1758, this time dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe. In the mid-eighteenth century the church had to be demolished. It was rebuilt in December 1816, and the viceregal city council rededicated it to the Virgin of Tepeyac. Since it was on a high piece of land the church was a useful lookout to watch over the entrance to the city.

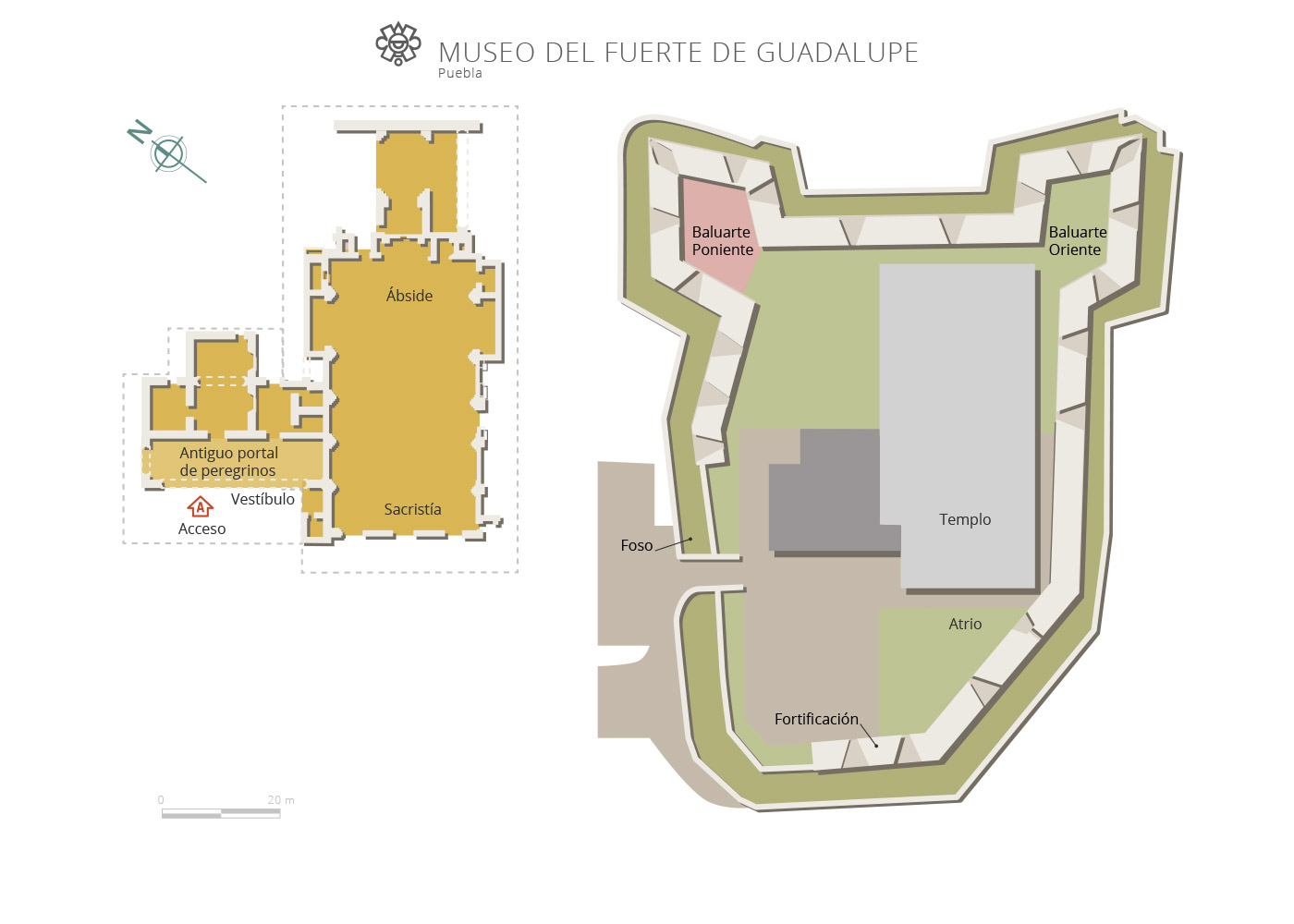

With its location between the port of Veracruz and the capital of the viceroyalty, the city of Puebla soon became one of the most important sites in the land, which is why fortification work on the church began in 1816. The fortified church was useful for the protection of the city. Salazar makes the point that the work was commissioned by the city council using the labor of prisoners and with the materials paid for by the citizens. The historian also states that the ground plan suggests that the initial plan was to build a square shape with bastions, but only the north frontage and east and west curtains were ever built. In 1862 Mexico was already independent when the engineer Joaquín Colombres prepared the fortification to deal with the threat of a French invasion. He improved the ditches and adapted the escarpment of the hill to create a natural defense.

The main section of the museum focuses on the Battle of Puebla. The exhibition shows that President Juárez ordered General Ignacio Zaragoza to take charge of Mexican strategy. Zaragoza was born in Espíritu Santo Bay in the state of Coahuila y Tejas, on the present-day Texas coast but at that time in Mexican territory. General Zaragoza commanded the Eastern Army from his quarters in the church and the Convent of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios in the city of Puebla, which is today at Calle 20 Norte, between 8 Oriente and 6 Oriente. Under his command were Generals Felipe Berriozábal, Francisco Lamadrid, Miguel Negrete and Antonio Álvarez, as well as Colonel Porfirio Díaz, among other officers. Troop numbers amounted to around 5,400 men, who came from Oaxaca, the “State of the Valley of Mexico,” San Luis Potosi and naturally also from the State of Puebla.

The museum describes how the battle began at about 11 a.m. with a fusillade from the Fort of Guadalupe, announced by the ringing of bells in the city. The first clash took place on the hill of Acueyametepec when the 6th Infantry Batallion commanded by General Negrete and formed of men from the Sierra Norte de Puebla, turned back an enemy advance. In the second clash the French gained ground, but their column was turned back for the second time by the combined gunfire and bayonet fighting of the Mexicans. The troops of our country began to corner them and the enemy started to retreat more generally. At 2 p.m. the French formation and tactics had been practically neutralized, but they carried on fighting.

The museum also shows that after coming down from the hill the French reorganized and tried to attack the suburb of Xonaca, where the sappers and Reforma troops commanded by Díaz turned them back. Because of the strength and daring of these Mexican soldiers, once again with bayonets drawn and with cavalry charges with drawn sabers, the French were finally forced to halt their advance and to retreat again. Some of their formations even fled in disorder. On the enemy’s left flank, the battle continued with the third charge of the French army. Around 3.30 p.m. the enemy general, the Count of Lorencez had formed a new column which he directed again at the Fort of Guadalupe, once more without success. The retreating enemy then headed towards Atlixco with heavy losses in men and a great loss of materiel. The exhibition shows that intense rain underscored the final defeat of the invaders.

The building was already well preserved as a historical monument, but it was consolidated as a museum under the Comprehensive Rehabilitation Project of the Forts Area carried out by the government of Puebla, supported by the Defense Ministry and INAH on September 8, 2012. A site gallery safeguards a collection of about 180 items, which commemorate and elucidate the victory of the Republic. Its launch coincided with the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Puebla, and it also commemorated the death of General Zaragoza from typhoid soon after the battle, on September 8, 1862.

The background to these events is extensive. Historical research by Celia Salazar Exaire has revealed that the hill where the Fort of Guadalupe was sited was known by the pre-Hispanic inhabitants as Acueyametepec, meaning the hill covered by agave cactus with an abundance of frogs. Once the city of Puebla had been founded in 1537, the Franciscans headed by Fray Toribio de Benavente built a hermitage dedicated to San Cristóbal. Years afterwards, when it had already been converted into a church, the Bethlehemite Brothers, an order of teachers and nurses founded in Guatemala in 1656, arrived at the shrine and before the turn of the century added a hospital building. From then onwards instead of being known as the church of San Cristóbal it was known as the church of Belem (Bethlehem). In 1756 an earthquake hit the city of Puebla, extensively damaging the church. It had to be rebuilt, and reopened its doors in 1758, this time dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe. In the mid-eighteenth century the church had to be demolished. It was rebuilt in December 1816, and the viceregal city council rededicated it to the Virgin of Tepeyac. Since it was on a high piece of land the church was a useful lookout to watch over the entrance to the city.

With its location between the port of Veracruz and the capital of the viceroyalty, the city of Puebla soon became one of the most important sites in the land, which is why fortification work on the church began in 1816. The fortified church was useful for the protection of the city. Salazar makes the point that the work was commissioned by the city council using the labor of prisoners and with the materials paid for by the citizens. The historian also states that the ground plan suggests that the initial plan was to build a square shape with bastions, but only the north frontage and east and west curtains were ever built. In 1862 Mexico was already independent when the engineer Joaquín Colombres prepared the fortification to deal with the threat of a French invasion. He improved the ditches and adapted the escarpment of the hill to create a natural defense.

The main section of the museum focuses on the Battle of Puebla. The exhibition shows that President Juárez ordered General Ignacio Zaragoza to take charge of Mexican strategy. Zaragoza was born in Espíritu Santo Bay in the state of Coahuila y Tejas, on the present-day Texas coast but at that time in Mexican territory. General Zaragoza commanded the Eastern Army from his quarters in the church and the Convent of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios in the city of Puebla, which is today at Calle 20 Norte, between 8 Oriente and 6 Oriente. Under his command were Generals Felipe Berriozábal, Francisco Lamadrid, Miguel Negrete and Antonio Álvarez, as well as Colonel Porfirio Díaz, among other officers. Troop numbers amounted to around 5,400 men, who came from Oaxaca, the “State of the Valley of Mexico,” San Luis Potosi and naturally also from the State of Puebla.

The museum describes how the battle began at about 11 a.m. with a fusillade from the Fort of Guadalupe, announced by the ringing of bells in the city. The first clash took place on the hill of Acueyametepec when the 6th Infantry Batallion commanded by General Negrete and formed of men from the Sierra Norte de Puebla, turned back an enemy advance. In the second clash the French gained ground, but their column was turned back for the second time by the combined gunfire and bayonet fighting of the Mexicans. The troops of our country began to corner them and the enemy started to retreat more generally. At 2 p.m. the French formation and tactics had been practically neutralized, but they carried on fighting.

The museum also shows that after coming down from the hill the French reorganized and tried to attack the suburb of Xonaca, where the sappers and Reforma troops commanded by Díaz turned them back. Because of the strength and daring of these Mexican soldiers, once again with bayonets drawn and with cavalry charges with drawn sabers, the French were finally forced to halt their advance and to retreat again. Some of their formations even fled in disorder. On the enemy’s left flank, the battle continued with the third charge of the French army. Around 3.30 p.m. the enemy general, the Count of Lorencez had formed a new column which he directed again at the Fort of Guadalupe, once more without success. The retreating enemy then headed towards Atlixco with heavy losses in men and a great loss of materiel. The exhibition shows that intense rain underscored the final defeat of the invaders.

January 1970

Map

-

+52 (222) 234 2009

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Directory

Coordinador Técnico Administrativo

Miguel Díaz Sánchez

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

01 (222) 234 2009