Ex Convento de San Andrés Apóstol

Founded in 1540 by Augustinian friars, this monastery preserves extraordinary polychrome murals and examples of Romanesque, Mudéjar and Plateresque styles can be identified on its walls with many indigenous additions. The three Panels of Epazoyucan with scenes from the life of Jesus, are the highlight.

Historic place

About the museum

Epazoyucan, whose name means “place with an abundance of epazote,” was an important town inhabited by indigenous groups of Chichimec and Nahua origin. Various tribes held sway over this territory and when the Spanish arrived it was the Mexica of the fiefdom of Texcoco who were in control.

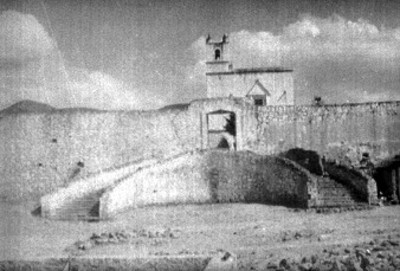

The Augustinian friars are credited with building the monastery in 1540, and the first stage might have consisted of the atrium, an open chapel and corner chapels. The chronicler Fray Juan de Grijalva wrote that “there were so many people that the house and church were built in seven months and seven days.” The second stage of construction was determined by the need to level the land on the current raised site of the monastery. This is why the church nave and the monastery’s cells were not finished until around 1563, according to the sources. The remains of the pre-Hispanic settlement were utilized, as became evident during the archeological excavations in the far south of the church.

The architectural complex and the artistic motifs which decorated it reflect the blend of building techniques used by the monks, such as Fray Lorenzo de San Nicolás, and by the indigenous people who worked on the construction.

The way in which the atrium, church, open chapel and corner chapels are laid out reflects the needs of the earliest missionary work, when the natives would congregate outside for mass, just as it later became convenient to enclose the precinct. Inside the church there is a sixteenth century alfarje (paneled) ceiling with 41-foot beams, one of which has been carved with cherubim and floral motifs. The bell tower in the northwest corner of the church is still preserved with bays on its four sides and turrets.

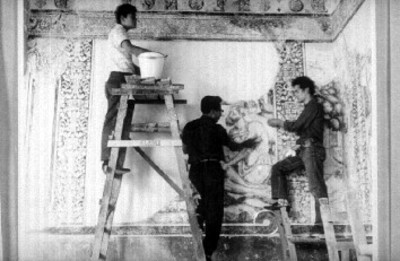

The cloister of the monastery has intricate architectural work with carved stone columns decorated in relief. There is a profusion of decorative elements which reveal the cultural and religious syncretism of indigenous and Hispanic cultures, but the most notable feature is the exceptional artistic quality of the carving work. Inside the former monastery there are extraordinary polychrome mural paintings with scenes of the Last Supper, the Passion and the Assumption of the Virgin. It is also worthy of note that in several parts of the monastery there are very old sgraffitos on the limestone, with lines of different thicknesses in the form of birds, stars, crosses and geometric figures.

Also known as the Community Museum of Tomazquitla, it houses a collection of 1,700 pre-Hispanic and viceregal period pieces, many of which are exhibited in a niche and 14 showcases spread between two galleries named La Cihuatecolotl (female owl) and the Colhua Gallery (broad shouldered man). They were given these names after the mythical founders of the place.

After hard work on the restoration, the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Hidalgo had the satisfaction of putting the majestic sixteenth-century paintings known as the “Epazoyucan Panels” back on display. They are on permanent display in the Altarpiece Gallery inside the viceregal Augustine precinct of San Andrés Apóstol. These three panel paintings form part of an altar, and are an example of how the life of Jesus was conveyed to the indigenous people, from his Birth, the Adoration of the Kings and up to two scenes of the Passion: the Prayer in the Garden and the Ecce Homo (“behold the man” in Latin).

The Augustinian friars are credited with building the monastery in 1540, and the first stage might have consisted of the atrium, an open chapel and corner chapels. The chronicler Fray Juan de Grijalva wrote that “there were so many people that the house and church were built in seven months and seven days.” The second stage of construction was determined by the need to level the land on the current raised site of the monastery. This is why the church nave and the monastery’s cells were not finished until around 1563, according to the sources. The remains of the pre-Hispanic settlement were utilized, as became evident during the archeological excavations in the far south of the church.

The architectural complex and the artistic motifs which decorated it reflect the blend of building techniques used by the monks, such as Fray Lorenzo de San Nicolás, and by the indigenous people who worked on the construction.

The way in which the atrium, church, open chapel and corner chapels are laid out reflects the needs of the earliest missionary work, when the natives would congregate outside for mass, just as it later became convenient to enclose the precinct. Inside the church there is a sixteenth century alfarje (paneled) ceiling with 41-foot beams, one of which has been carved with cherubim and floral motifs. The bell tower in the northwest corner of the church is still preserved with bays on its four sides and turrets.

The cloister of the monastery has intricate architectural work with carved stone columns decorated in relief. There is a profusion of decorative elements which reveal the cultural and religious syncretism of indigenous and Hispanic cultures, but the most notable feature is the exceptional artistic quality of the carving work. Inside the former monastery there are extraordinary polychrome mural paintings with scenes of the Last Supper, the Passion and the Assumption of the Virgin. It is also worthy of note that in several parts of the monastery there are very old sgraffitos on the limestone, with lines of different thicknesses in the form of birds, stars, crosses and geometric figures.

Also known as the Community Museum of Tomazquitla, it houses a collection of 1,700 pre-Hispanic and viceregal period pieces, many of which are exhibited in a niche and 14 showcases spread between two galleries named La Cihuatecolotl (female owl) and the Colhua Gallery (broad shouldered man). They were given these names after the mythical founders of the place.

After hard work on the restoration, the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Hidalgo had the satisfaction of putting the majestic sixteenth-century paintings known as the “Epazoyucan Panels” back on display. They are on permanent display in the Altarpiece Gallery inside the viceregal Augustine precinct of San Andrés Apóstol. These three panel paintings form part of an altar, and are an example of how the life of Jesus was conveyed to the indigenous people, from his Birth, the Adoration of the Kings and up to two scenes of the Passion: the Prayer in the Garden and the Ecce Homo (“behold the man” in Latin).

Map

An expert point of view

Álvaro Ávila Cruz

Centro INAH Hidalgo

Practical information

Tuesday to Sunday from 09:00 to 17:00 hrs.

$75.00 pesos

Benito Juárez s/n,

Epazoyucan, Hidalgo, México.

Epazoyucan, Hidalgo, México.

From the city of Pachuca take highway 130 for Tulancingo. After 16 km take the turn off to the right that leads to Epazoyucan; after 4 km you will arrive at the convent.

Services

-

+52 (771) 714 35 20; +52 (771) 714 39 89

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

FACEBOOK

Directory

Director del Centro Inah de Hidalgo

Héctor Alvarez Santiago

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (771) 714 35 20, ext. 228013