At Bonampak, the ancient Mayan city nestling in the forest, a building measuring 55 feet long by 13 feet wide and close to 17 feet high has been preserved almost intact, despite having been abandoned more than 1,000 years previously. The building is important because of its mural painting. Known as the Building or Temple of the Paintings, it is divided into three rooms, each with its own entrance, numbered one to three, from left to right. Above each entrance is a thick stone slab, known as a lintel, with two carved personages. The lintels of the first two rooms feature an important warrior capturing a prisoner in battle around 789 AD, while the right hand entrance, or number 3, shows an event which took place 50 years earlier. The room 1 lintel presents a portrait of the last known governor of Bonampak, the lord Chan Muwan II; the lintel of room 2 features the governor of the powerful city of Yaxchilán, the lord Jaguar Shield II, who in turn was the brother-in-law of Chan Muwan II, and the room 3 lintel shows a figure who could be the father of Chan Muwan II. Chan Muwan II, who assumed power at Bonampak in the year 776 AD, and must have governed till close to the year 800, ordered the construction of the Building of the Paintings in order to decorate it with a series of events or stories of great importance to him and his city.

No other pre-Hispanic structures have been found to date with such extensive, well-preserved or richly detailed murals for the study of ancient Mayan culture. Generally speaking, it is the forest that gradually destroys these marvelous records of times past, as the trees that grow on the temples tend to pull them down, and even if they remain standing, the thin layer of lime covering the interior and exterior walls is prised away by small roots and humidity, to fall and crumble on the ground. The fact that the murals in the Building of the Paintings have survived is all the more remarkable for these reasons.

On the outside, the upper part of the building has three niches, one at each end and one in the center, inside of which are the remains of a stucco figure of a seated person. Very probably the sculpture in each niche corresponds to the governor referred to in the entrance lintel situated below. Inside the building, each room has a bulky and wide seating ledge on each of the three interior walls. In each room, the murals cover walls, arches, roofs and the sides of the ledges.

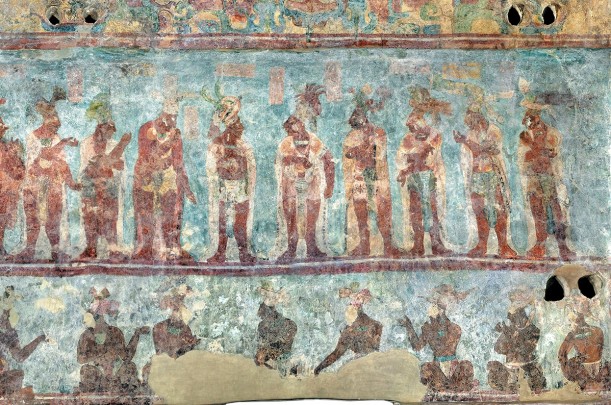

The three rooms tell a story which begins in room 1, in which the great Chan Muwan II appears standing together with other important men of his family, his wife, mother and daughters. Chan Muwan II presents a baby who appears to be carried by an assistant; perhaps it was his first male child, and in accordance with the rules of the culture, he would govern upon the death of Chan Muwan. Another part of the room shows Chan Muwan II and two other personages dressed in luxurious clothes, jewels and with an enormous long headdress of green, possibly quetzal, feathers. These three figures head a type of procession including, amongst others, musicians and people with masks of mythological Mayan beings, such as the lizard, an animal associated with the fertility of the land. Among the musical instruments depicted can be seen maracas, trumpets made from large sea shells and turtle shells used as drums. The purpose of this religious procession was to prepare Chan Muwan II and his people to ask the gods for good fortune in the next war and to offer up the victory to the gods so they would watch over his successor.

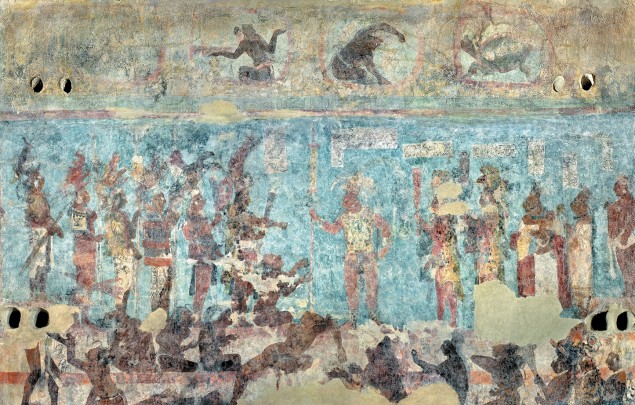

Room 2 narrates the great battle fought by Chan Muwan II and his brother-in-law, the governor of Yaxchilán, against usurpers in Bonampak allied with the city of Sak´t´zi. Various prisoners were captured, who elsewhere in the story are presented before Chan Muwan II on the great pyramid of Bonampak known as the Acropolis, where they are tortured by having their nails pulled out before being sacrificed.

The story continues in the third room where several personages in eye-catching attire are engaged in some sort of dance on the high steps of the Acropolis in front of the Building of the Paintings. Two of the dancers have one of the victims tied by their hands and feet and we observe how they throw him upwards to where Chan Muwan II is presiding over the ceremony. This is the culmination of the ritual to gain the favor of the gods for the future governor of Bonampak. Finally Chan Muwan II, his family and the courtiers who were depicted in room 1 appear in a calm place, possibly a palace, conversing about the events already described, richly dressed with short skirts and loincloths of beautiful material, and covered with thin and transparent capes. The scene focuses on the mother, wives and daughters of Chan Muwan II bleeding themselves with the spines from the tail of a stingray in honor of the protector gods of Bonampak.

It seems that the heir of Chan Muwan II never did come to power in Bonampak, and that something happened in the city before he could succeed. Perhaps long and severe droughts blighted the corn and other crops needed to feed the region’s towns and cities, which undoubtedly provoked wars, the fall of the kings of this era and the abandonment of their cities. The forest grew over everything and more than 1,000 years passed before these magnificent murals and their history were discovered.

All these events were from the final years of this city, an era in which Chan Muwan II destroyed or buried all the stelae or carved stones referring to previous governors of the city, except for lintel 4 located in building 6, whose carvings show Chan Muwan I, governor around the year 600 AD, nearly 200 years before Chan Muwan II.

Without doubt, Bonampak finds no parallel in Mesoamerica on account of its pictorial legacy, and the people and government of Mexican have a great responsibility to guarantee its conservation and endurance for future generations.