Malinalco

The place where Malinalxóchitl is venerated

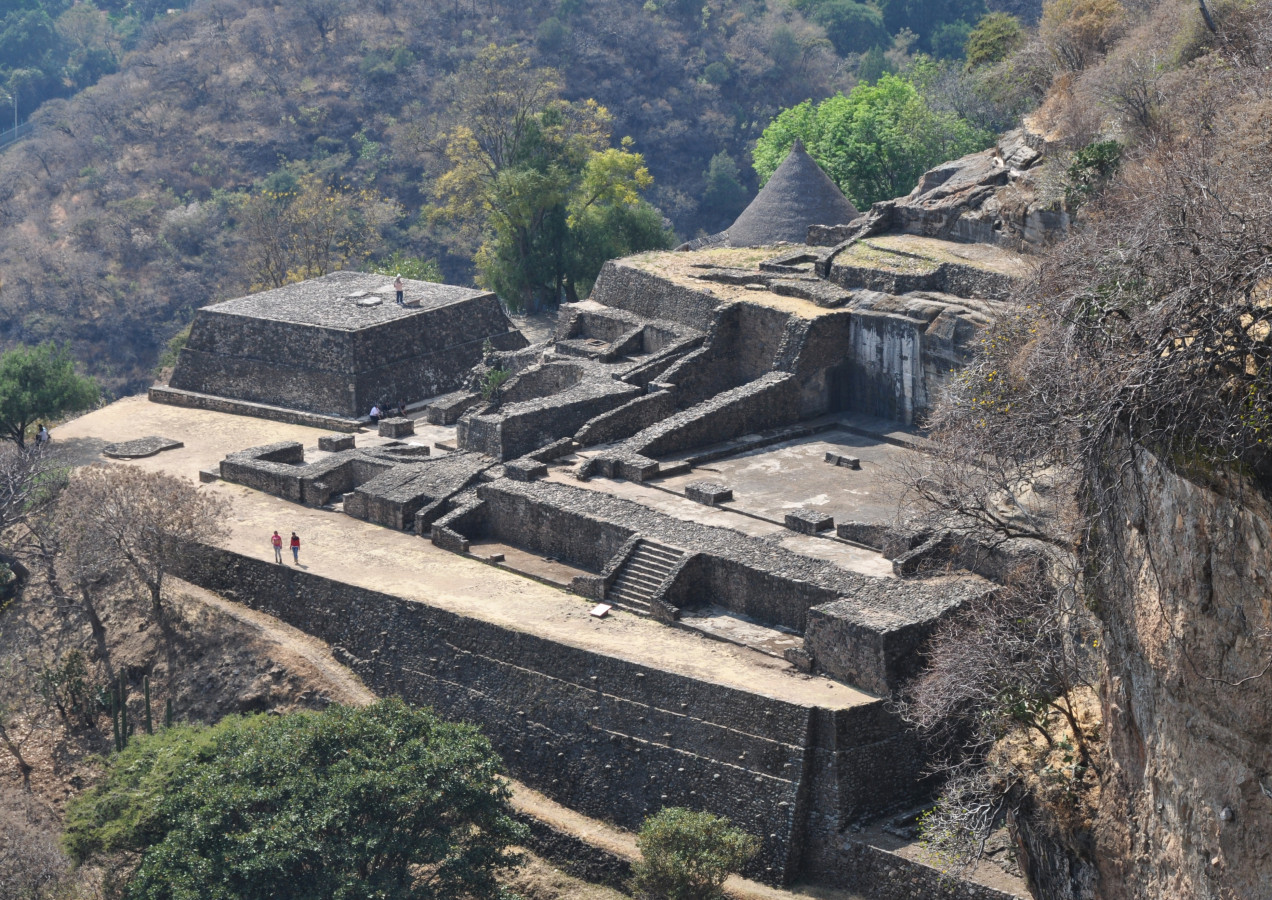

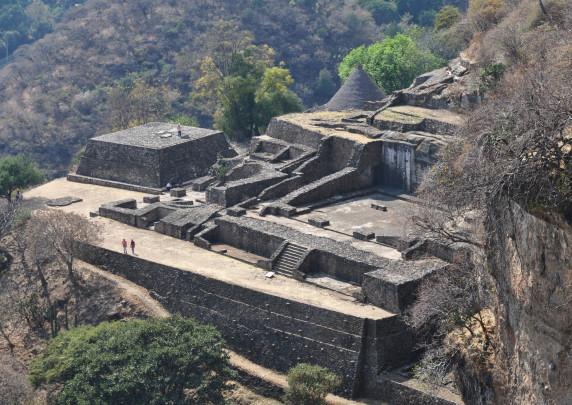

This site is unique in Mesoamerica, as it was carved in one piece out of an enormous rock on the edge of a cliff for military initiation purposes. The site was created by the Mexica not long before the Spanish conquest, and is dedicated to the initiation of Eagle and Jaguar-Ocelot warriors. It contains splendid sculptures of these symbols.

About the site

Originally a Matlatzinca city, Malinalco was conquered by the Mexica in approximately 1476. It served as a checkpoint for trade routes, a garrison and a point for protecting an important aqueduct to Tenochtitlan. Besides training and consecrating elite warriors, it was a sanctuary to the cult of war gods, as well as agricultural deities. Its name could refer to Malinalxóchitl (“the place where Malinalxóchitl lives," “where she is worshipped” or in turn “flower of the plant for making rope," “the malinalli flower”) goddess of witchcraft and fateful divination, sister of Huitzilopochtli and Coyolxauhqui.

Inhabited since before the current era, it received influence from Teotihuacan (only recognizable from pottery remains) and then benefited from and partially controlled trade with Tierra Caliente (the current states of Morelos and Guerrero) and the Central Mexican Plateau. The ritual practice of human sacrifice performed on warriors captured in the “xochiyáoyotl” or “flower war” seems to have been important here.

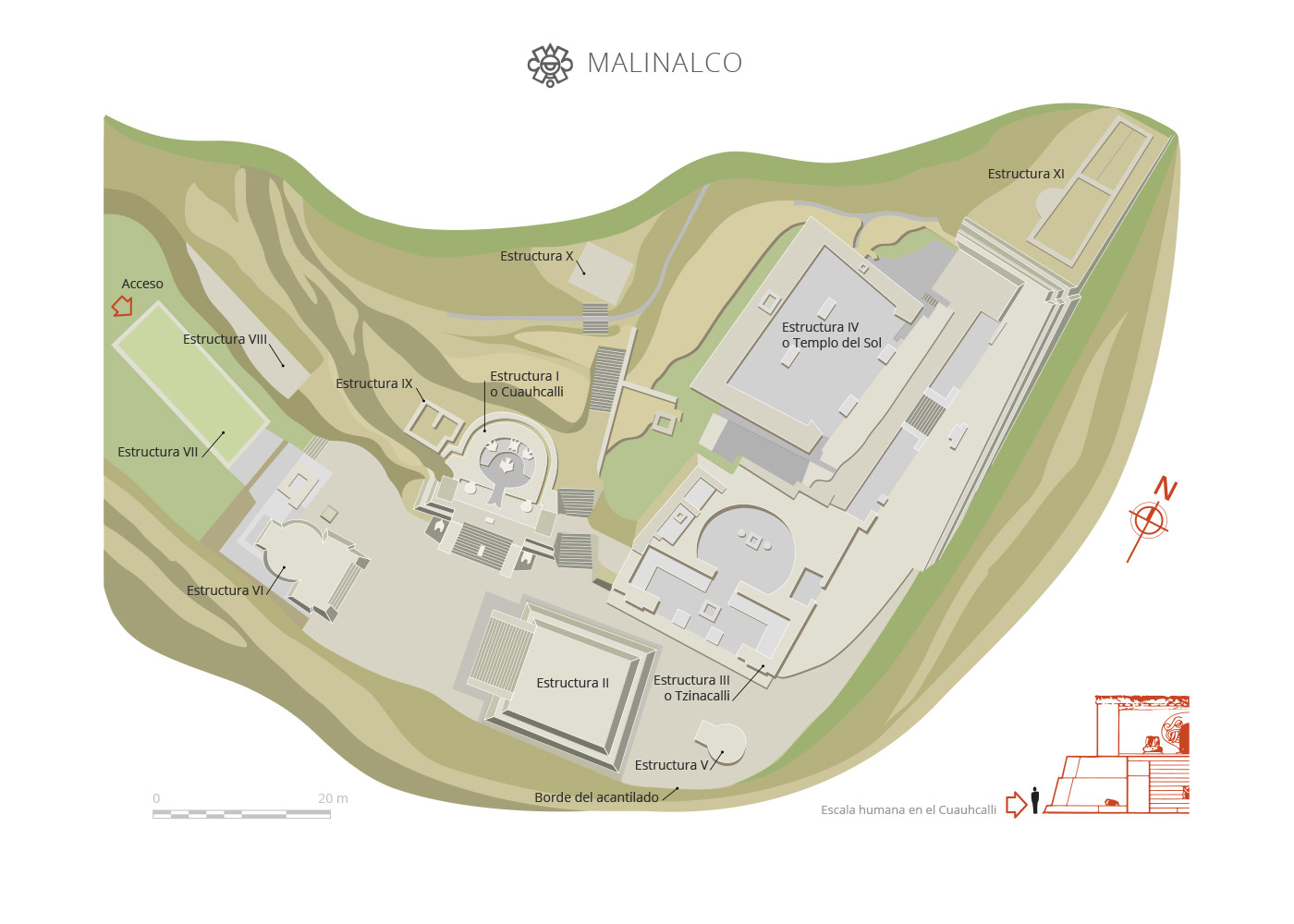

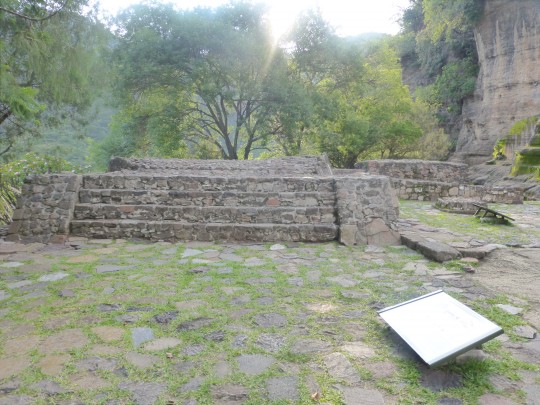

Its most noteworthy monuments are in the Cuauhtinchan (“eagle’s aerie”) complex, which is the best-preserved portion. The monolithic temple known as the Cuauhtinchan, which was engraved to celebrate military rituals, stands out among the carved buildings, as it is the only one of its kind in Mesoamerica. The settlement has a complicated layout, and this appears to have been for the purposes of defense. Councils of war were undoubtedly held in one of its structures.

For its part, the Cuauhcalli (“house of the eagles”), also called Temple I or the Monolithic Temple owing to its having been carved out of solid rock, was the setting for military and probably religious gatherings. Its roof has been reconstructed from local materials such as palm and timber, recreating the original on the basis of details of clay statuettes found in the archeological zone as well as the post holes and rainwater channels carved from the rock of the building itself. It has a staircase flanked with two ocelot sculptures and a third one in the center (which probably served as a banner stand), as well as runoff channels to protect the building from the rain. Its main door is in the shape of the jaws of a serpent which represents the Earth Monster. On the floor outside the door, we can also see a carving of a forked tongue, in front of which there is an opening for depositing offerings. This door leads to an area surrounded by a circular walkway, on which we observe the figure of an ocelot and two eagles with their wings spread as if in flight. However, these actually represent fine rugs, because their claws are stretched behind them and not below the body. In the case of the ocelot, its paws are in a similar pose: open and not about to pounce. There is an eagle with its wings tucked behind it in the middle of the sanctuary, behind which is a hole for depositing the ritual blood offering.

It is believed that the remains of warriors who had fallen in battle were cremated in Building III or Tzinacalli (“house of the burners”).

Letters written by Hernán Cortés mention that, in 1521, he entrusted Captain Andrés de Tapia with conquering and bringing to heel the Mexica garrison and population of Malinalco, after which the survivors were then handed over in tribute.

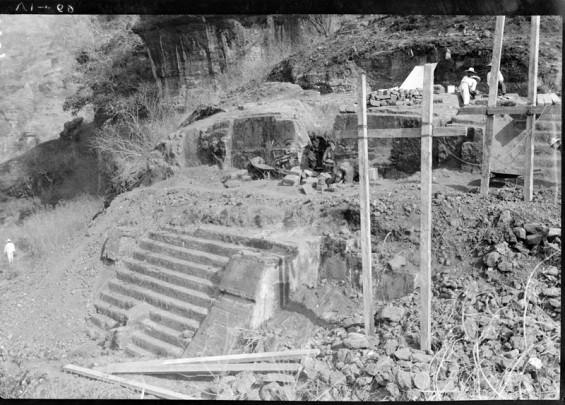

The site was first explored in 1905, the results of which were described by Doctor Francisco Plancarte y Navarrete, the second bishop of Cuernavaca, who believed that Malinalco had been dedicated to the cult of Xiuhtecuhtli, the god of fire. A second exploration led by the archeologist Enrique Juan Palacio in 1925 gave a clearer idea of the size and importance of the zone. Recent explorations and systematic excavations conducted by the INAH have shed a great deal of light on this surprising site.

Inhabited since before the current era, it received influence from Teotihuacan (only recognizable from pottery remains) and then benefited from and partially controlled trade with Tierra Caliente (the current states of Morelos and Guerrero) and the Central Mexican Plateau. The ritual practice of human sacrifice performed on warriors captured in the “xochiyáoyotl” or “flower war” seems to have been important here.

Its most noteworthy monuments are in the Cuauhtinchan (“eagle’s aerie”) complex, which is the best-preserved portion. The monolithic temple known as the Cuauhtinchan, which was engraved to celebrate military rituals, stands out among the carved buildings, as it is the only one of its kind in Mesoamerica. The settlement has a complicated layout, and this appears to have been for the purposes of defense. Councils of war were undoubtedly held in one of its structures.

For its part, the Cuauhcalli (“house of the eagles”), also called Temple I or the Monolithic Temple owing to its having been carved out of solid rock, was the setting for military and probably religious gatherings. Its roof has been reconstructed from local materials such as palm and timber, recreating the original on the basis of details of clay statuettes found in the archeological zone as well as the post holes and rainwater channels carved from the rock of the building itself. It has a staircase flanked with two ocelot sculptures and a third one in the center (which probably served as a banner stand), as well as runoff channels to protect the building from the rain. Its main door is in the shape of the jaws of a serpent which represents the Earth Monster. On the floor outside the door, we can also see a carving of a forked tongue, in front of which there is an opening for depositing offerings. This door leads to an area surrounded by a circular walkway, on which we observe the figure of an ocelot and two eagles with their wings spread as if in flight. However, these actually represent fine rugs, because their claws are stretched behind them and not below the body. In the case of the ocelot, its paws are in a similar pose: open and not about to pounce. There is an eagle with its wings tucked behind it in the middle of the sanctuary, behind which is a hole for depositing the ritual blood offering.

It is believed that the remains of warriors who had fallen in battle were cremated in Building III or Tzinacalli (“house of the burners”).

Letters written by Hernán Cortés mention that, in 1521, he entrusted Captain Andrés de Tapia with conquering and bringing to heel the Mexica garrison and population of Malinalco, after which the survivors were then handed over in tribute.

The site was first explored in 1905, the results of which were described by Doctor Francisco Plancarte y Navarrete, the second bishop of Cuernavaca, who believed that Malinalco had been dedicated to the cult of Xiuhtecuhtli, the god of fire. A second exploration led by the archeologist Enrique Juan Palacio in 1925 gave a clearer idea of the size and importance of the zone. Recent explorations and systematic excavations conducted by the INAH have shed a great deal of light on this surprising site.

Map

Did you know...

- Malinalco is the only monolithic site in Mesoamerica. It was all carved from a single rock, with tools also made of stone.

- Six monumental structures are located on the summit of Cerro de los Ídolos (Hill of the Idols). The different sections of the Cuauhtinchan could be overlooked from this area, which is about an acre in size and 6,971 feet above sea level.

- It was a strategic point for the Mexica empire’s interests between 1476 and 1521 AD.

- The Cuahcalli is the only temple dedicated to war rituals we know of to date. Eagle and ocelot warriors pierced themselves here and inserted jewelry in the cartilage between their nostrils and in the front of their chins.

An expert point of view

The Cuauhtinchan and the Cuauhcalli, destiny and culmination of the Mexica military elite, guardians of the sun’s eternal return

José Hernández Rivero

Centro INAH Estado de México

-

+52 (714) 1473013

-

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Directory

Responsable

Sonia Georgina Sosa Chávez

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (722) 213 9581