In the pre-Hispanic period the end of a time period or calendar cycle was celebrated every 52 years, when the start of the two calendars, the solar (xiuhpolhualli) and ritual (tonalpohualli) coincided. This celebration was known as xiuhmolpilli (the binding of the years), which on the one hand meant the end of time, and on the other the start of a cycle and the time of the birth of the sun and the rebirth of the world.

Without a doubt the end of a calendar cycle implies uncertainty and is a frightening prospect in any culture. The pre-Hispanic peoples feared that the end of the 52 year cycle would mean an end to life itself, and they believed that the sun would not rise again and that the world would disappear. To this calamity was added the notion that unincarnate beings (tzitzimime) were trying to destroy the world and hinder the birth of the sun, and would devour humanity. For this reason children and pregnant women were protected with masks.

To avoid an end-of-cycle catastrophe, families would destroy their belongings, images of their gods and household utensils on the final day of the cycle. They would put the fire out and stay waiting in the darkness inside their homes. In the meantime, the priests would start the binding of the years ceremony (toxiuhmilpilia) with a procession to Huizachtepetl, known today as Cerro de la Estrella, the place where the new fire would be lit.

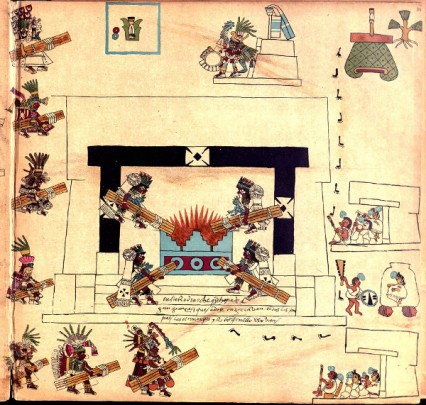

The Codex Borbonicus illustrates how this ceremony was carried out. On the left side of the sheet is a procession of priests carrying their bundles of reeds towards the temple and in the center are the four people chosen to light the sacred home fire to renew the fire for the regeneration of time, and the commencement of a new 52-year cycle. On the right hand side of the sheet are the families inside their homes wearing their protective masks. Finally in the upper part is the sign 2 reed, the date on which the New Fire was celebrated as well as the birth of Huitzilopochtli. For this reason, this deity and his temple are painted in the upper part of the sheet (figure 1).

Once the bonfire was lit, flames were passed to light the temple and house fires in all neighborhoods. In this way the celebration would end the following day with festivities to celebrate the birth of the sun and to honor the god Huitzilopochtli.

The permanent exhibition gallery of the Xolotl Museum features archeological items connected to this ceremony for the renewal of the calendar cycle: an altar or the burial of the years, a cylindrical sculpture representing the dead cycles and the reproduction of a mural painting which was detached from a small altar located on the front platform of the monument.

Altar or tomb of the years in the Xolotl Museum

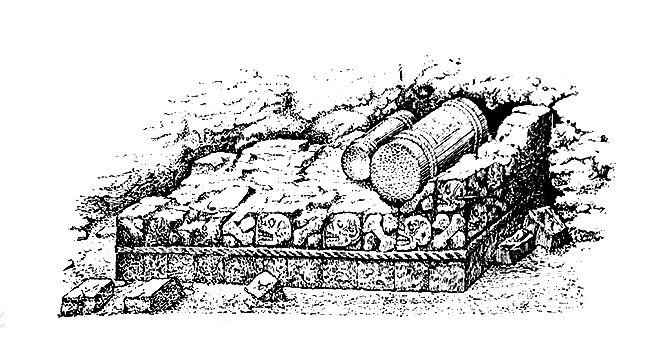

The altar consists of ashlars of tezontle stone with sculptures of human skulls in profile alternating with long crossed bones (omicallo). These figures were certainly related to death, but they were also placed on top of a rope which symbolizes the binding (figures 2 and 3). On the other hand there is a similar altar found by Leopoldo Batres in the center of Mexico City, inside of which were found two cylindrical sculptures representing the binding of the reeds used in the New Fire ceremonies. The discovery made it possible to conclude that this type of altar was dedicated to the burial of the expired time (figure 4).

Sculpture of Xiuhmolpilli representing the dead cycles

This type of cylindrical sculpture is similar to the bound reeds which were burnt in the New Fire ceremony, and these were commonly known as xiuhmolpilli because of their relationship with this ceremony. The ends and center of this sculpture, which is in the Xolotl Museum, include a representation of the string which kept the reeds tied, with two areas worn down in a cone shape which might have been rubbed with a sharp point to produce the fire (figure 5).

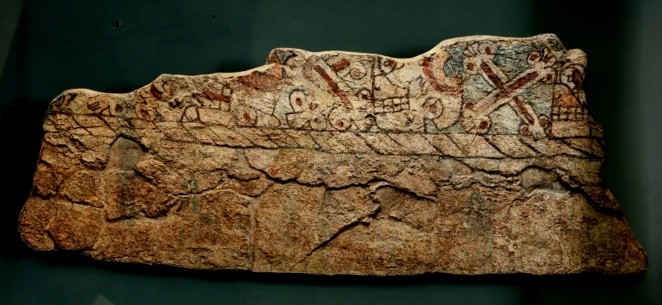

Mural painting of the altar or sepulcher of the skulls

The painting is concerned with the cycle of the years because in addition to the iconographic elements (skulls and crossed bones), it was found inside the small altar located in the front platform of the great plinth of Tenayuca. Likewise, this altar has representations of skulls and long crossed bones on three of its sides (figure 7). Without a doubt the imagery of both is related to death, nevertheless, this is no ordinary representation of death, rather it is a symbolic representation of the lost years or cycles. When it was discovered in 1925 nothing apart from the painting was found inside, and for this reason it is possible that once upon a time it also contained a bundle of perishable reeds.