Museo de Sitio El Cerrito

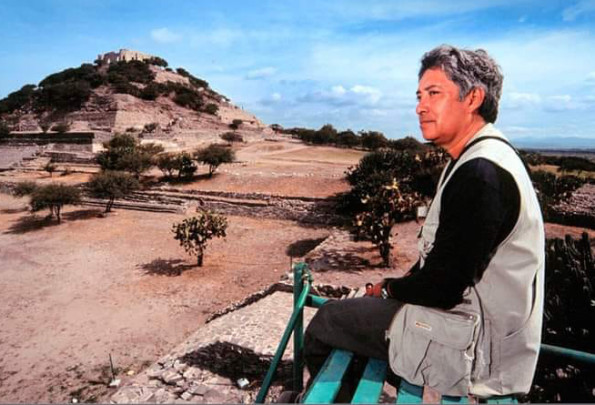

The museum presents the history of the archeological zone, taking the Toltec worldview as its starting point. The El Cerrito site is the northernmost ceremonial center in Mesoamerica and the site museum exhibits items recovered during the excavation. It is the museum for the most important archeological zone in the state of Querétaro, covering 350 square meters.

About the museum

The exhibition layout describes the ceremonial center of El Cerrito, which had clearly delimited plazas, altars, and a pyramid with 13 sloping-walled terraces each with a height of 1.8 to 2 meters, giving a total of 30 meters. The museum aims to help visitors understand, enjoy, and interpret the historical and spiritual power of the site. Its history is narrated by means of four exhibition sections that display some 170 items, most recovered during the archeological excavation and research project. To these are added two private collections that were turned over to the INAH for safekeeping, and objects belonging to the Queretaro Regional Museum.

One of the most notable pieces is a stele with the image of the goddess Itzpapálotl (the butterfly with obsidian wings), a deity venerated by the Toltecs at El Cerrito. This is an important work because the goddess appears in a number of codices, but only three sculptures have been found that depict her: one at a site in Tula, Hidalgo, one at Tenango del Aire, State of Mexico, and this one. Over the years of exploratory excavations, multiple pieces of evidence related to Itzpapálotl have been found at El Cerrito, clearly indicating that it is the central deity of the site.

The exhibition begins with the Toltecs’ conception of their mythical origin, which defines them as a civilized people who know where they come from, and why their goddess Itzpapálotl accompanies them. To recreate the myth, the exhibition presents an image from the Map of Cuauhtinchan II. The second section of the exhibition focuses on the architecture of sacred spaces, setting out how a ceremonial center is constructed, the materials used, the pigments, and the sculptures, so important to the Toltecs. This section displays a model with a hypothetical reconstruction of the pre-Hispanic site at its apogee. The third part of the exhibition addresses the consecration of the space, exploring the Toltec tradition of making offerings of all their constructions. Whenever work on a building commenced, offerings were made such as incense burners, figurines and shells. At El Cerrito two offerings of this type were found, one of which is on display in the new museum. The fourth section of the exhibition deals with everyday offerings: once the site was in operation as a ceremonial center it was used for collective and private ceremonies which saw participants coming from different parts of Mesoamerica to bring offerings they deposited here. At some point El Cerrito became a major sanctuary that received pilgrims from all across Mesoamerica, as shown by the wealth of different materials such as spindles decorated with tar from the Huasteca region, shells from the Pacific, a figurine from the Altos de Jalisco, a vase from the border between Mexico and Guatemala, stone axes, pots, and shell and stone beads.

A series of drawings were prepared for the museum showing the sacred routes and trade routes that led to the spread of ideas throughout the region. This tradition of pilgrimage continued even after the arrival of the Franciscans, with the Otomi peoples continuing to place ‘pagan’ offerings. This led to the placement here of the Virgin of Pueblito, one of the principal Marian images in the colonial period, and for which a sanctuary was later constructed in the nearby village of San Francisco Galileo.

One of the most notable pieces is a stele with the image of the goddess Itzpapálotl (the butterfly with obsidian wings), a deity venerated by the Toltecs at El Cerrito. This is an important work because the goddess appears in a number of codices, but only three sculptures have been found that depict her: one at a site in Tula, Hidalgo, one at Tenango del Aire, State of Mexico, and this one. Over the years of exploratory excavations, multiple pieces of evidence related to Itzpapálotl have been found at El Cerrito, clearly indicating that it is the central deity of the site.

The exhibition begins with the Toltecs’ conception of their mythical origin, which defines them as a civilized people who know where they come from, and why their goddess Itzpapálotl accompanies them. To recreate the myth, the exhibition presents an image from the Map of Cuauhtinchan II. The second section of the exhibition focuses on the architecture of sacred spaces, setting out how a ceremonial center is constructed, the materials used, the pigments, and the sculptures, so important to the Toltecs. This section displays a model with a hypothetical reconstruction of the pre-Hispanic site at its apogee. The third part of the exhibition addresses the consecration of the space, exploring the Toltec tradition of making offerings of all their constructions. Whenever work on a building commenced, offerings were made such as incense burners, figurines and shells. At El Cerrito two offerings of this type were found, one of which is on display in the new museum. The fourth section of the exhibition deals with everyday offerings: once the site was in operation as a ceremonial center it was used for collective and private ceremonies which saw participants coming from different parts of Mesoamerica to bring offerings they deposited here. At some point El Cerrito became a major sanctuary that received pilgrims from all across Mesoamerica, as shown by the wealth of different materials such as spindles decorated with tar from the Huasteca region, shells from the Pacific, a figurine from the Altos de Jalisco, a vase from the border between Mexico and Guatemala, stone axes, pots, and shell and stone beads.

A series of drawings were prepared for the museum showing the sacred routes and trade routes that led to the spread of ideas throughout the region. This tradition of pilgrimage continued even after the arrival of the Franciscans, with the Otomi peoples continuing to place ‘pagan’ offerings. This led to the placement here of the Virgin of Pueblito, one of the principal Marian images in the colonial period, and for which a sanctuary was later constructed in the nearby village of San Francisco Galileo.

February 2019

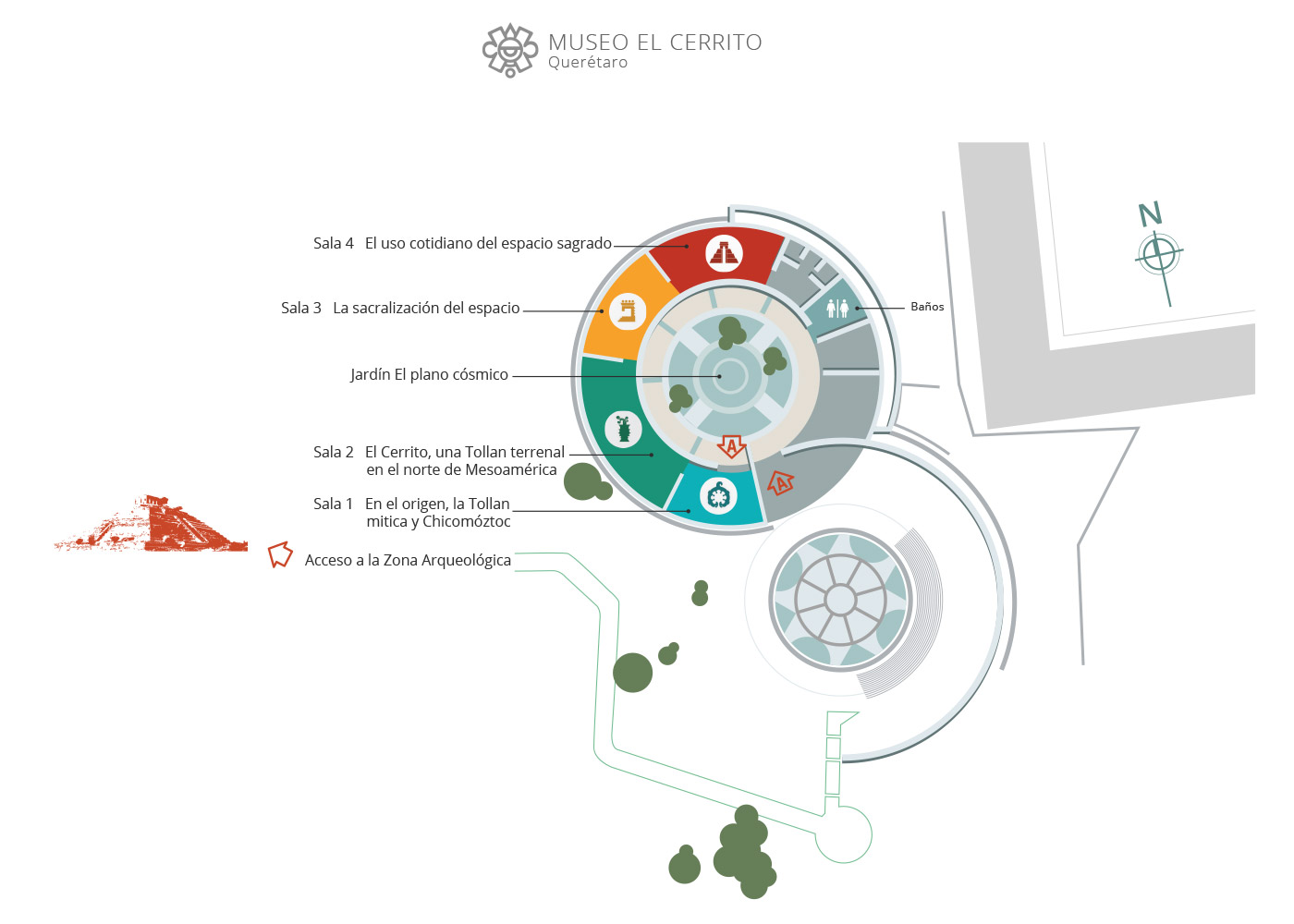

Map

Directory

Directora

Claudia Pilar Dovalí Torres

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (442) 225 30 87

Coordinación Comunicación Educativa

Martha Sánchez Martínez

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

+52 (442) 225 11 32